Why Youth and the Future of Culture? A Curator’s Introduction

“Why elevate youth voices?”

As a member of Generation X, I feel the need to establish a little youth-adjacent credibility before I can answer this question.

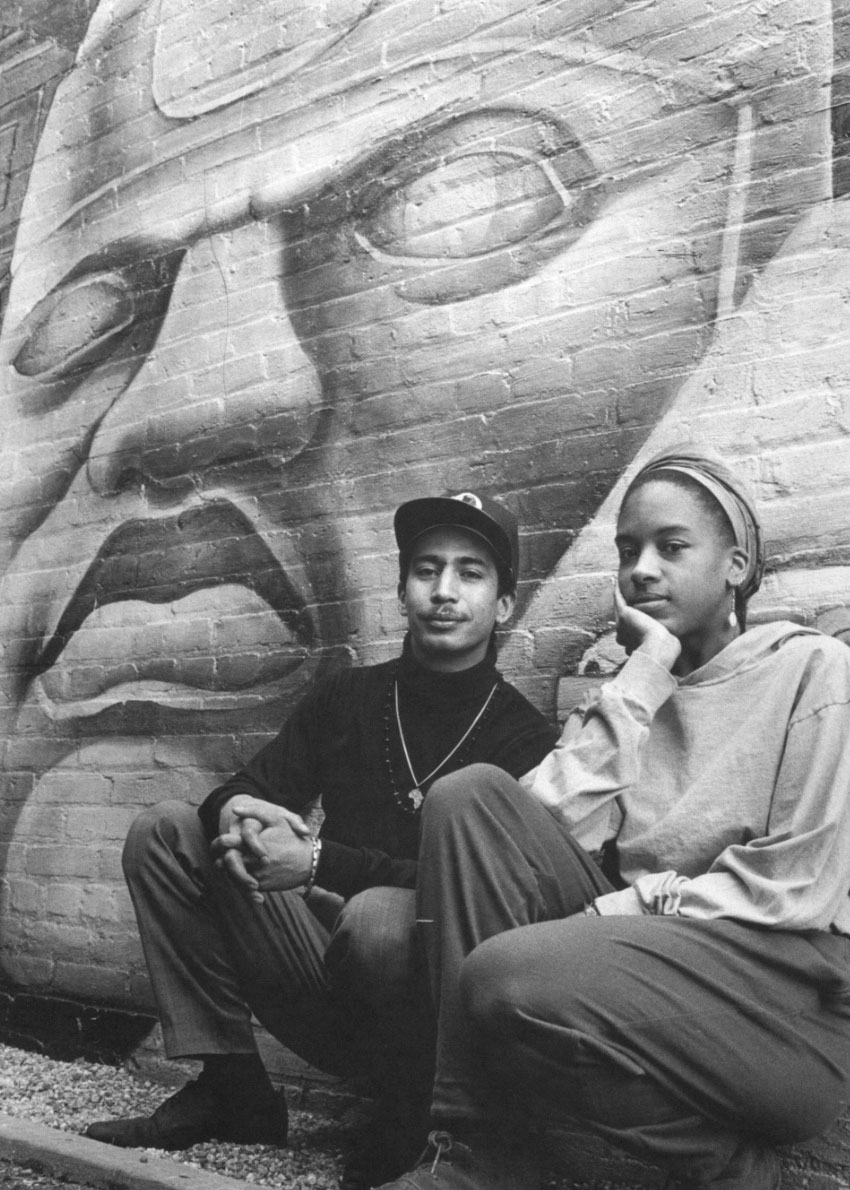

I graduated from the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, D.C., in 1984. With no prospects for the future beyond whatever jobs we could find, my classmate Quique Avilés and I decided that we had something to say.

In 1985, we co-founded the LatiNegro Theatre Collective, an ensemble of young Black and Brown artists. Inspired by the late Brazilian educator and philosopher Paolo Freire and his artistic collaborator Augusto Boal, LatiNegro did participatory theatre with youth. Our characters were the young people who were talked about in congressional hearings but rarely had a chance to share their worlds, and our stages were street corners, classrooms, group homes, and prisons. Precocious and cocky and, dare I say, brave, we created original works that explored our lives, dreams, desires, and fears.

Although the collective disbanded in 1995, my worldview continues to be informed by that experience. I believe that art is important labor, and, like our bodies, our creativity must be fed. I also believe the future is malleable, and it is youth who are in the best position to reimagine what it might be—not because they will inherit the future but because they have the imagination and desire to shape the future they want to see. I knew this when I began my journey as a young artist in the 1980s, I witnessed it during my years as an educator, and I see it now as I work with Gen Z for the upcoming Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

In 2025, the Festival will become a space where reimagining is welcomed and encouraged. The program Youth and the Future of Culture will explore how young artists, filmmakers, musicians, poets, storytellers, students, and others, from across the country—and a handful from other parts of the world—are sustaining and building community by embracing culture and tradition. Animated by interconnected themes that express how youth both innovate and engage with culture, the program will highlight the work of organizations committed to elevating youth voices and nurturing their creativity, play host to families that are keeping generational traditions alive, and feature individuals who have carved out a space to construct something beautiful.

Since the Festival’s inception in 1967, youth have participated in many programs; we have considered how children and youth express themselves, make sense of their worlds, and carry on tradition. The Festival explored play and performance in programs such as Children’s Folklife (1978) and Kids’ Stuff (1993), demonstrated how traditions are passed on between generations in Children’s Program (1982) and Circus Arts (2017), celebrated youth wordsmiths in Giving Voice: The Power of Words in African American Culture (2009), and highlighted how youth serve as bridge builders in On the Move: Migration Across Generations (2017). In many ways, Youth and the Future of Culture is the culmination of decades of Festival programming.

As the Festival approaches its sixtieth anniversary, building new audiences and supporting the next generation of cultural practitioners will ensure that many of the traditions and practices that we have featured over the years—and many others we are just learning about—continue to thrive. Youth and the Future of Culture is also a stepping stone to the 2026 Festival of Festivals, which will mark 250 years since the signing of the Declaration of Independence. What better way to reflect on the nation’s past than by looking forward to what the next generation has to offer?

Thank you to the amazing Michelle banks from the @SmithsonianFolk festival for spending the day with the @DCDPR Deanwood Radio broadcast college students on Spring Break. We’re so excited about the partnership announcement coming soon pic.twitter.com/gSHAcnMLkb

— Bootsy Vegas (@bootsyvegas) March 15, 2025

While planning for this program, I, along with my colleagues, have visited community centers, classrooms, studios, workshops, and other places where youth gather and learn to witness their work, hear their stories, develop program themes, and identify some of the things they would want to see represented on the National Mall. We talked to young people who were just beginning their journeys as artists and makers, and others who were already committed to their craft. We also met with elder practitioners who reflected on their experience as young learners and what it means to mentor youth.

Of the messages that I heard during those encounters, one was always clear: youth are not a monolith and cannot be easily defined. They are poetic and multilingual, contemporary and old-school. They vibe with hip-hop, country, classical, gospel, jazz, and K-pop. They are urban farmers, rural DJs, teaching artists, and community organizers. They learn in schools and with family, and on their own. They dream big and see possibilities and have always been at the vanguard of creativity, innovation, and change. And as one student explained to me when I asked how they would define youth, “It’s not just an age. It’s also energy.” I witnessed that energy everywhere I went.

In Eagle Butte, South Dakota, I met Gabriela, a teen intern at the Cheyenne River Youth Project who explained Lakota winter counts to me with knowledge and poise. During a gathering of students at the Stax Music Academy in Memphis, Tennessee, I was surprised when a group of teenagers discussed how ancestors like Bill Withers and Otis Redding—who, by the way, was only twenty-three when he wrote and recorded “(Sittin’ on) the Dock of the Bay”—influenced their music. In Baltimore, Maryland, I spent time with young teaching artists at Wide Angle Youth Media who are now patiently sharing the training they received with the next generation of creators. And in Sacramento, California, I had the honor of breaking bread with elders from the Royal Chicano Air Force; now in their seventies and eighties, some of them were just out of high school when they began producing the graphic arts work that would galvanize the Xicano movement of the 1970s.

This year’s Festival participants are contributing to legacies that previous generations began and, in some cases, constructing their own. They include Ava and Lila Delgado, who are poised to become the fourth generation of luthiers to carry the Delgado name; Malcolm Davis, who represents three generations of “Affrilachian” storytellers; Fiona Stowell, who has been playing the fiddle since she had the strength to hold her instrument; and sidewalk astronomer and photographer Gael Gomez, who shares his passion for the cosmos with community members using a telescope he constructed himself. These are just a few of the young people who will be joining us on the National Mall in July to share their craft and tell their stories.

Youth and the Future of Culture will also honor mentors—those who recognize that supporting and nurturing the next generation is part of their role as culture and tradition bearers. They include John Hankins, Jeff Poree, and Darryl Reeves from the New Orleans Master Crafts Guild, who are training the next generation of master crafts people and preservation specialists; Virginia Diediker and the late Nati Cano, who started a program to preserve mariachi music by offering classes to youth in the San Fernando Valley; and Myaamia educator Darryl Baldwin, who decided to raise his children in his disappearing heritage language and has since devoted his life to revitalizing and teaching the language to others.

In addition to the performances, demonstrations, narrative discussions, food demonstrations, and workshops the Festival is known for, I imagine the program as a collaborative space for participants and community members. You can participate in master classes with Festival participants and their mentors, and, in the spirit of innovation, Festival participants are encouraged to collaborate on new works and ideas.

So, “why elevate youth voices?”

Rather than discussing youth inheriting the future, Youth and the Future of Culture challenges us to reflect on and engage with them right now. As fifteen-year-old Harmony Belle Devoe, the current Vermont youth poet laureate—who will be joining us at the Festival—writes, “the past can’t be changed, but the future can be rearranged.” If the things I’ve witnessed on my research trips are any indication, the young people who will join us on the National Mall this summer are ready to rearrange and reimagine the future.

Michelle Banks is the lead curator for the Youth and the Future of Culture program at the 2025 Smithsonian Folklife Festival.