What’s at the Heart of Our Tarot Fascination?

LONDON — Ask any tarot reader about the origins of the popular cartomancy practice, and you’ll get a variety of answers. “It’s from ancient Egypt.” “It was Renaissance Italians.” “They’re connected to playing cards.” “Nobody really knows.”

Tarot – Origins & Afterlives at the Warburg Institute starts by looking at this history, without overshadowing the magic in this practice. “When an aesthetic or visual form is doing so much work in culture, as tarot is, I want to know why,” noted Jonathan Allen, one of the show’s curators, in an interview with Hyperallergic. “One can start beginning to answer the question by looking at the history of the phenomenon — why is tarot doing all this conceptual work and what kind of work is it doing culturally?”

Grounded partly in the research of the institute’s namesake, art historian Aby Warburg, the show features Warburg’s research in 1909 into tarot in the section Tarot Atlas. Among the rare items on view are the 15th-century Mantegna Tarocchi, a precursor to the modern tarot deck (likely used more for play than divination), and the 19th-century woodcuts that make up the Tarot of Marseille, a deck still in common usage today.

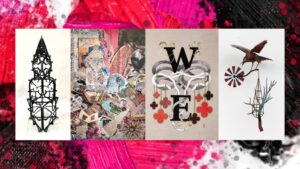

The exhibition also dives into a major historical turning point in the history of tarot. In the 1780s, French Freemason and scholar Antoine Court Gébelin declared that it “was not a mere pack of playing cards,” the exhibition text states, “but a repository of arcane wisdom known as the ‘Book of Thoth,’ originating in Ancient Egypt.” Other fascinating items are notions of tarot as a “story machine,” through a novel by Italo Calvino in which the characters can only communicate with tarot cards, and Suzanne Treister’s famous HEXEN 2.0 and HEXEN 5.0 decks, which help orient us to alternative futures; a full view of the popular Rider-Waite-Smith deck, illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith; and a Tarotkammer, a collection of contemporary decks inspired by the Renaissance-era Wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities.

I asked Allen and his fellow curator, Martina Mazzotta, about tarot’s enduring appeal. “Tarot and its combinatory system of symbols mean it is ideally suited to telling stories in many different areas and [for] different purposes,” Allen explained. “This functional diversity surfaces throughout our exhibition.” It’s also, as Mazzotta said, “a source of wonder.”

Perhaps one of the more interesting insights that emerges from the exhibition is the way tarot has been embraced in the modern era — somewhere in between a body of esoteric knowledge and a game. “There’s a snowball effect where tarot is now like a complex game that has more in common with its ludic and recreational origins than it does with its deeply occult history.” Allen observed. “It’s a third phase of the tarot — a serious game, modeling complexity.”

The curators politely declined my invitation for them to give a reading during our interview — they noted that they’re scholars and not practitioners — but they did share two cards that they love: “The World” from Tarocchino Mitelli (1660) and “The Juggler” from the Austin Osman Spare tarot deck (1906). While “The Juggler” does not appear in most contemporary tarot decks I’ve seen, it visually resembles “The Magician” from the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, while the 17th-century Tarocchino Mitelli card recalls the legendary image of the Greek Titan Atlas.

The world indeed feels very heavy right now, as so many of us, like Titan, carry the burdens of our time. If I were to take the liberty of combining these cards into a meaningful reading, I might point out that they accomplish exactly what tarot allows for so many of us today — bringing forth a smart mixture of play and ancient wisdom that might help us juggle our reality, with at least some of the will and dexterity of “The Juggler.”

Tarot – Origins & Afterlives continues at The Warburg Institute (Woburn Square, London, England) through April 30. The exhibition was organized by Jonathan Allen, Martina Mazzotta, and Bill Sherman (whose favorite deck is the Sola Busca).

The Warburg Institute will host a series of related events on April 24, 26, and 30. Check the website for details.