A Must-See Michael Armitage Show Inaugurates David Zwirner’s Latest New York Gallery

In 2015, an Eritrean teenager named Saron told Vice News of her harrowing journey from her war-torn home country to Europe via the Libyan capital of Tripoli, a 4,000-mile odyssey that included imprisonment, endangerment, and bearing witness to the torture of fellow female migrants. The Vice story continued to linger with the painter Michael Armitage, so much so that he returned to this agonizing tale nine years later in a work called Path (2024), which is making its debut this month in a haunting solo show at David Zwirner in New York.

In Path, hooded figures—the women whom Saron saw get tortured with nails, possibly—are huddled together behind animals at a trough. A man joins those animals, smashing food into his mouth while a baby looks on. Many of those details aren’t in the Vice report, and few would even know that a journalistic investigation inspired this piece, had Armitage himself not mentioned it at a press preview on Thursday.

But there is one detail in Path that is also mentioned by Vice: the endless sea, visible through a tiny aperture in the painting’s black and blue. “We know a lot of people died there,” Saron told Vice. The painting summons that knowledge through a poignant mix of fact and fiction.

All of the works in Armitage’s Zwirner show are about migration, and many of them could even be counted as history paintings, placing him within a longstanding genre through which generations of artists have rendered major real-world happenings onto canvas. Most of the time, though, artists working in that tradition tend to present their work as a form of reporting: Robert Longo’s 2018 drawing showing migrants sliding along a gigantic wave, for example, is hyper-detailed depiction of this ongoing crisis, suggesting that it is realer than the truth itself. That work is a clear allusion to Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1818–19), one of the most famous history paintings of all time. For his part, Armitage presents his own homage in the 2024 painting Raft (ii), in which a boat filled with refugees navigates roiled waters.

Yet unlike the Géricault and Longo works, Armitage’s painting is blurry: one yellow-shirted figure, having apparently fallen overboard, now melts away into the tide. The work appears hazy, like a half-remembered dream. It’s unstable, just as history and memory itself often is, particularly in its most traumatic moments.

Armitage’s palette goes heavy on dandelion yellow and vibrant azure, recalling the color compositions of the Post-Impressionists and the Nabis artists of the late 19th century. Both movement’s artists used their hues to create internal landscapes that existed beyond reality, and Armitage’s hues work toward a similar goal, moving his paintings out of our world, into one that is only semi-imagined. His colors look particularly strong at David Zwirner, where they are exhibited in a new Annabelle Selldorf–designed gallery filled with natural light—a precious resource in New York.

Selldorf, the architect behind the Frick Collection’s recent renovation, has previously conceived many other galleries in Zwirner’s empire, including several in New York. But she was not initially expected to do this one, which came about only after another, to be located two blocks over, fell through. This just-opened venue has just one story and measures 18,000 square feet. It’s modest by mega-gallery standards, and puny in comparison to the five-story, 50,000-square-foot behemoth Zwirner initially planned. Zwirner blamed his developer’s “financial headwinds during Covid” for the about-face, but it turns out those headwinds have steered him in the right direction: his spare new gallery is a pleasant place to see art.

Not counting the atrium, the gallery has three spaces, all of them currently occupied by Armitage. One has new sculptures that appear like wood carvings, even though they are done in patinated bronze. Each represents an episode from the life of Jesus Christ, whom Armitage said he views as a migrant. One depicts two disembodied, gnarled feet bound together; it could represent the deposition from the cross or the dead body of a refugee shown elsewhere here.

The bronze works have cold and austere surfaces, and therefore are not as interesting as the paintings on view here, which are all done on lubugo bark cloth. Unlike canvas, the cloth does not naturally take well to oil paint: it tears upon being stretched, and its textured surface makes for uneven terrain. When painted, the cloth often looks a bit like skin, especially because of the way that Armitage stitches together his pieces, leaving behind visible scars, perhaps ones accumulated along an arduous journey.

The London- and Nairobi-based artist has related the cloth to its use by the Buganda people of Uganda, who utilize it as funerary shrouds, and to its sale by merchants in his home country of Kenya, where he once found coasters made of lugubo at a Nairobi tourist market. “Different cultural pressures result in the loss of some things, whilst other things are kept and others are brought back,” he said in the catalog for a 2023 Kunsthaus Bregenz survey of his work. His paintings, like his materials, are about what gets altered in transit.

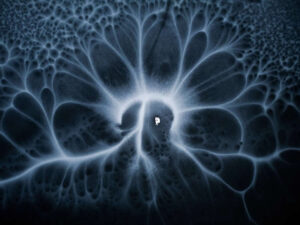

Yet the curious thing about Armitage’s depictions of harrowing subject matter is that they are often also beautiful. One figure in an untitled 2024 painting here is shown clutching a baby amid swirls of blue. There are holes in the figure’s thigh and head, where they appear like gashes or bullet holes. But perhaps there’s another way of looking at these ruptures. Maybe they’re also portals to alternate dimensions, small windows into worlds beyond our own—worlds in which humans care more deeply for each other.