Translating Wounds: Wuchao Feng’s Feminine Ecologies and Transcultural Alchemy

In the silence between materials, Wuchao Feng makes language. Salt crystals crunch underfoot, uneven pearls spell aphasic fragments, and a red heap dissolves into migration trails—each gesture a poetics of the inarticulable. If her earlier work offered a visual grammar of fluid identity, her most recent explorations in salt and pearl have shifted toward a dense, embodied metaphysics—one in which materiality is both archive and oracle.

Feng, born in the port city of Ningbo and now based in London, mines her work from the sediment of a dual inheritance: saltwater economies and the migratory churn of postnational subjectivity. “Dilution” (2020), a long-evolving performance and installation project, maps a symbolic topography of identity through the dispersal of sea salt. Here, Feng treats salt not only as substance but as semiotic residue—each crystalline trace a metaphor for the disarticulation of the self in transit. The female body becomes a salt body, not fixed but in states of gathering and dissipation.

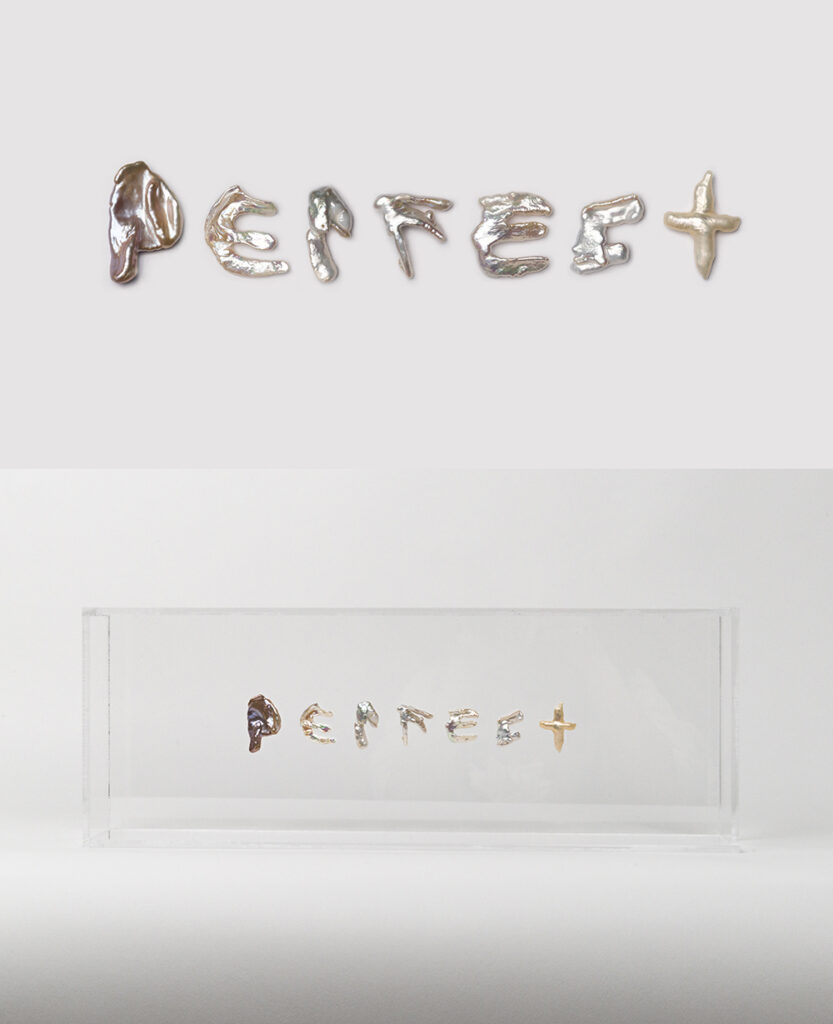

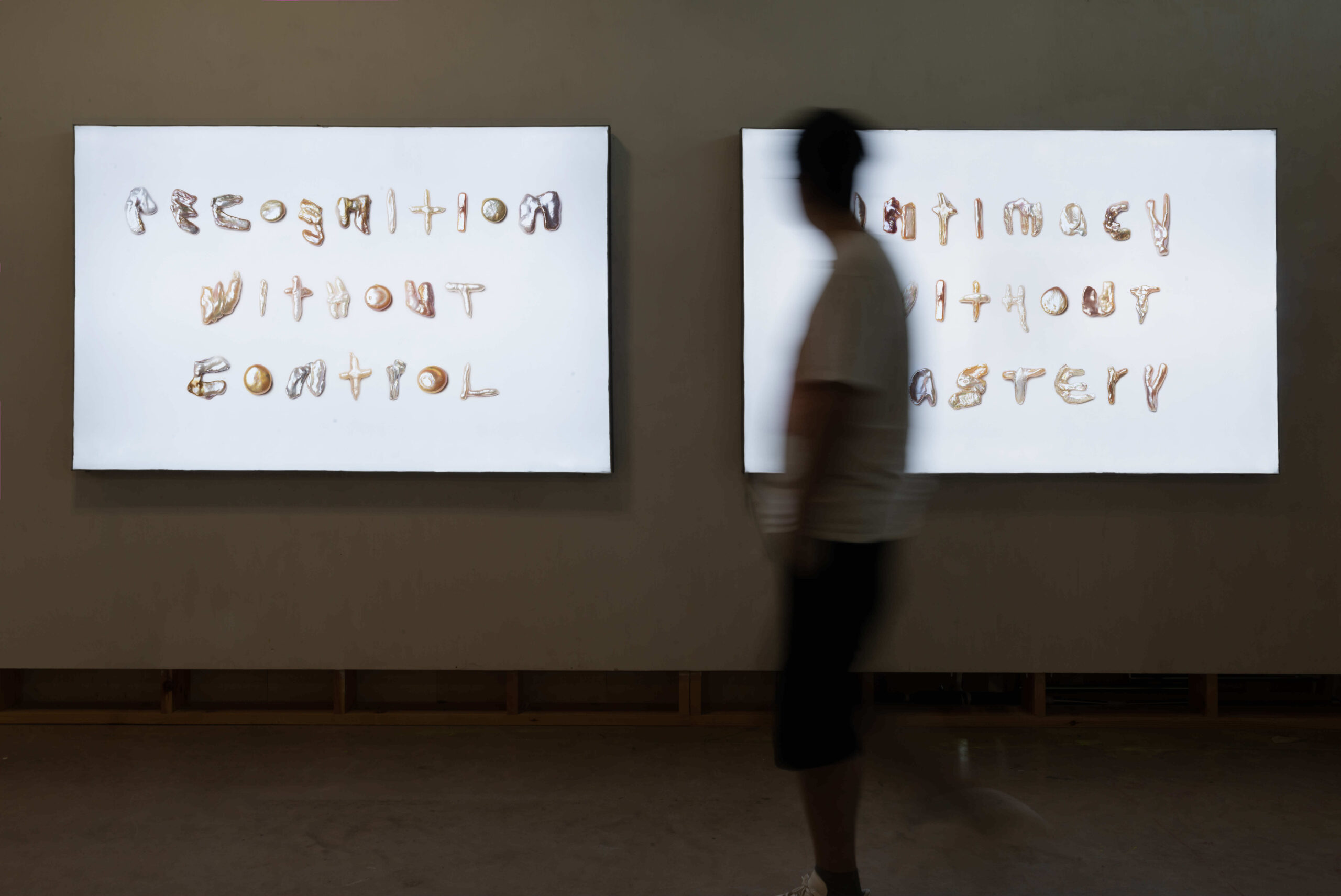

The image of the scar, a healing wound that refuses to vanish, haunts Feng’s Pearl series even more explicitly. Unlike salt, which liquefies with time, pearls calcify around intrusion. This fact—biological yet metaphorical—becomes the heart of Feng’s formal inquiry. Her “Pearls of Wisdom” (2023) series uses misshapen, rejected pearls to form words and phrases. In the delicately grotesque forms of these pearls, one reads trauma not as rupture, but as the beginning of formation. A wound enters the oyster; a gloss of survival accrues. These textual clusters—“Recognition without Control,” “Intimacy without Mastery”—hover in backlit vitrines, glowing with the quiet urgency of unspoken truths.

Where salt dispersed the subject, pearls insist on coherence, but a coherence born through resistance. These are not metaphors of feminine delicacy but of a kind of mineralized endurance. The feminist logic is clear: the body absorbs its violence and metabolizes it into form, not closure. Echoing theorists like Elaine Scarry and Judith Butler, Feng understands the body not only as a site of injury but as a site of inscription. Her alphabet pearls do not just spell—they scar. And yet they shimmer.

What is striking is the way Feng situates these processes in a transcultural terrain. The salt, harvested from Ningbo’s traditional salt fields, references histories of labor and survival specific to China’s coastal economies. The pearls, sourced from flawed industrial batches, nod to both the feminized labor of pearl cultivation and the global circuits through which value is assigned to aesthetic purity. Feng’s use of these materials, and her refusal to aestheticize them into perfection, instead, she materializes cultural specificity through the lens of personal—and gendered—trauma.

Language becomes unstable under her hands. Not just because it is formed from irregular pearls, but because the words themselves stutter across meaning. Feng is not interested in clarity but in the failures of translation: between cultures, between bodies, between pain and speech. Her phrases, suspended like relics in lightboxes, function as open wounds—ungrammatical, yet exact in their evocation. There is no neutral tongue here; there is only the muteness of affect, slowly reconstituted into something almost—but not quite—sayable.

In conversation, Feng has spoken of her own struggles with expression across languages—Mandarin, English, dialects, and the voiceless syntax of trauma. This multiplicity is not resolved in her work but embraced as the condition of its genesis. Like a poem composed from borrowed alphabets, her practice reclaims the right to speak with brokenness.

It is within this fragmentary ethos that her engagement with feminist and transcultural discourse becomes most potent. Her salt trails crisscross, interrupt, and disappear—much like the diasporic experiences that inform them. And her pearls do not align neatly into syntactical order but drift into loose constellations—suggesting not mastery of language, but intimate cohabitation with its limits.

If some artists construct worlds, Feng reconstructs injuries. Her installations are not landscapes but woundscapes—terrains where pain, memory, and place collide. Yet they are never solely about her. In refraining from autobiographical legibility, she allows her viewers to enter these landscapes not as voyeurs but as witnesses.

In an era when identity is often weaponized as static declaration, Feng offers something riskier: an aesthetic of becoming, of slow accumulation, of intimate estrangement. She does not illustrate theory but enacts it—in salt, in pearl, in the invisible membranes between language and material. Through her work, trauma is neither fetishized nor resolved. It is translated, haltingly, into a shared visual syntax—one that, like all good metaphors, both reveals and refuses.

As she continues her practice within the context of the UK’s art world—most notably through her residency at Bomb Factory Art Foundation—Feng’s work promises to deepen these lines of inquiry. Her commitment to bio-material research and feminist methodologies speaks not only to personal evolution but to a broader collective reckoning with how we remember, how we endure, and how we speak.

Wuchao Feng does not ask us to understand. She asks us to listen—to what language cannot hold, but materials can.

The post Translating Wounds: Wuchao Feng’s Feminine Ecologies and Transcultural Alchemy appeared first on Our Culture.