At 98, Thaddeus Mosley Is Still Building His Forest of Wood Sculptures

Thaddeus Mosley’s wood sculptures weigh hundreds of pounds and typically rise high into the air, soaring far above the 98-year-old artist, who stands just 5 feet and 3 inches tall. But despite the gigantic size and monumental weight of his sculptures, Mosley approaches his elegant creations with ease, nimbly picking up their heavy pieces and balancing them so that they look light and delicate.

He works alone, using a small crane to move his pieces of wood when he feels it absolutely necessary, and he has never thought of hiring a studio assistant. “What would they do?” he asked me when I visited his Pittsburgh studio in April.

Located in an industrial building on the city’s North Side, Mosley’s cavernous studio was host to an array of sculptures in various stages of completion. Some, featuring multiple pieces of cherry and walnut, were already smoothed by Mosley, who wields gouges of varying sizes to scoop out his wood’s surfaces. Other wood slabs awaited further carving and were stood up vertically.

Mosley’s basement-level studio is so large that, when I called out to announce my presence, he did not immediately hear me. With no one there to retrieve me, I was left alone with his sculptures in quietude. Many of them resembled totems composed of large branches stacked against one another. Some had already begun to look like bodies—limb-like elements show up regularly in Mosley’s art—while others had only just begun to take form. It felt like being in an empty forest, and I immediately recalled a 2020 poem that Sam Gilliam had written for Mosley, whom Gilliam termed the “keeper of the trees.”

When I finally found Mosley seated beneath a wall collaged with clippings of all kinds (New York Times reviews of shows by Lorna Simpson and Mark Bradford, pictures of jazz greats, ads for auctions and exhibitions), he compared his process to judo. “It’s not just the idea of using the force that someone brings against you,” he said. “You learn how to use someone’s charge.” Carving his trees functions similarly. “You learn where the center of gravity is. A lot of the idea is based on the concept of weight in space.”

Thaddeus Mosley, Gate III, 2022.

Courtesy Public Art Fund

For seven decades, Mosley has been producing works such as these, making him a legend in Pittsburgh. With his daughter Tereneh, Mosley once appeared on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, the famed children’s TV show shot in the city, and he first exhibited his art at the Carnegie Museum of Art in 1968. The musician John Coltrane hung out with him when he spent time in Pittsburgh, and he won the Pittsburgh Center of the Arts’s Artist of the Year award before he committed to being an artist full-time.

“Thad is really a hero in Pittsburgh,” Brendan Dugan, the founder of Karma, the New York–based gallery that has shown Mosley since 2020, told ARTnews. “You know, when you walk around with him, it’s like walking around with Elvis.”

Until very recently, however, Mosley went unnoticed just about everywhere else. He has never participated in a Whitney Biennial, a Documenta, or a Venice Biennale; the Museum of Modern Art has never shown or collected his work. But following an appearance in the 2018 edition of the Carnegie International, a closely watched survey of contemporary art curated that year by Ingrid Schaffner, Mosley’s art has gained a wider following.

Exhibitions with Karma have received due praise, with the Times terming the most recent one, in New York this past spring, “spectacular.” Institutional shows have followed: one at the Seattle Art Museum last year set Mosley’s art beside first-class sculptures by Alexander Calder, a modernist of international renown. Gradually, his art has also begun entering museum collections: the Whitney acquired its first sculpture by him in 2024.

Now, Mosley is having one of his biggest shows to date, at New York’s City Hall Park, where he is exhibiting gigantic bronze versions of his wood creations. The exhibition, organized by the Public Art Fund, is a belated recognition of Mosley’s influence. “I see him as a pillar of Black artistic production in so many facets,” Jenée-Daria Strand, the show’s curator, told ARTnews. “He’s someone that has been an anchor in the field for a very long time and yet hasn’t had a show like this.”

Work by Thaddeus Mosley at City Hall Park.

Courtesy Public Art Fund

The City Hall Park show features a 15-foot-tall sculpture from 2022 called Gate III—viewers can pass through its archway—and the 2020 bronze Benin Strut, which appears like two wooden wings extending from the back of a slender body. Mosley titled the show “Touching the Earth,” a reference to a bell hooks essay that begins: “When we love the earth, we are able to love ourselves more fully. I believe this.” Mosley clearly does, too. Of his materials, he told me, “I always think that these trees have a new life.”

Mosley doesn’t create sketches, as most sculptors do, and works slowly and deliberately—his last Karma show featured 12 works, the entirety of his output for the two and a half years preceding the exhibition’s opening. He approaches his wood as Michelangelo supposedly did for the block of marble that birthed his David, visualizing the end product in his mind and carving until he reaches it. “Sometimes I get surprised, and it turns out a little better than I thought it was going to be. But I pretty much have an idea of what the piece is going to look like,” he said.

Mosley is always respectful of his surfaces: he doesn’t sand his materials on personal policy, and if there is a gnarl or a whorl in the wood, he’ll leave it be in the final work. He makes marks to delineate how he intends to balance his 100-pound wood pieces, but always in chalk. “You can always remove them,” he said of the chalk lines he gently scrawls.

He used to salvage downed trees and haul them to his studio for his art. In another person’s hands, this wood would’ve been desirable for carving, and so, he said, “you had competition in collecting trees back then.” These days, however, he purchases his wood from sawmills in Pennsylvania with the money gained from the sales of his art. He was quick to note that those funds weren’t readily available until recently. “I never made any money ’til I joined Karma,” he said.

And yet, Mosley has plugged away, maintaining a rigorous schedule in the studio even while working full-time jobs. Schaffner, the curator who put Mosley in her Carnegie International, compared his process to jazz, which the sculptor often uses as a soundtrack while creating his work. “He works quite slowly, so he’s sort of keeping time with the rhythm of his mark-making, which you can almost hear,” she said. “It’s like this beat, very methodical.”

Thaddeus Mosley, 1990.

Photo Anire Mosley/Courtesy the artist and Karma

The beat began in 1926, the year Mosley was born in New Castle, Pennsylvania. “In that time,” Mosley said, “coal was king,” and so his father took a job as a coal miner while his mother worked as a seamstress. In an interview with Pittsburgh Quarterly, Mosley said that he decided as a kid that “the mines just weren’t for me.” Still, it’s apparent that the mines left their mark: in our interview, Mosley credited his father’s hard labor with instilling in him a work ethic that he maintains today.

After high school, Mosley served in the Navy, then went to New York for a spell before relocating to Pittsburgh, a city that was much less expensive. He enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh with plans to study English and journalism. While taking a world history course in 1948, he was assigned a book that featured images of Constantin Brancusi’s modernist sculptures beside pictures of the African objects that had inspired them. The book made a lasting impression on Mosley.

“I didn’t know that Brancusi was influenced by African tribal art at that time,” Mosley said. “But I was very struck by how the curvatures [of Brancusi’s works] reminded me of Senufo birds.” He continues to draw his inspiration today from African art, collecting objects such as Chiwara masks and wooden pieces crafted by the Dogon people in Mali. Strand, the Public Art Fund curator, said that these objects continue to offer Mosley “the deepest exploration possible of form and balance.”

Works by Thaddeus Mosley at the 2018 Carnegie International.

Photo Bryan Conley/Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

In the 1950s, at a Kaufmann’s department store in downtown Pittsburgh, Mosley encountered Scandinavian design objects resembling birds that were made from wood. “I said, ‘I can do that,’” Mosley recalled. And so he did, kicking off a practice that is still ongoing today.

Mosley was working in the same modernist paradigm as Brancusi and Isamu Noguchi, who distilled forms seen in nature to their basics, then remade them in bronze, wood, and marble. Brancusi and Noguchi were able to spend all day in their studios, but Mosley could not—he had to make a living. He took a part-time position at the Pittsburgh Courier, where he wrote sports journalism, and later spent years working at the post office, where he sorted mail. “I could save all my energy, all my thinking power for my work,” he said. The Postal Service job also afforded him stability: “One thing I didn’t have to worry about was being laid off.” He retired in 1997.

Though Mosley exhibited extensively within Pittsburgh during this time and even afterward, it wasn’t until Schaffner’s 2018 Carnegie International that many out-of-towners became aware of him. Dugan, the Karma founder, was so moved by Mosley’s work in the International that he asked Schaffner for the artist’s phone number and set up a studio visit.

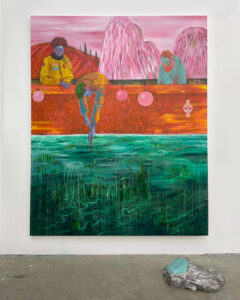

Thaddeus Mosley’s 2025 Karma show in New York.

Courtesy the artist and Karma

Dugan pointed out that despite Mosley’s meteoric rise over the past few years, Mosley remains humble, much like his art. “You’re casually seduced by the way he’s thinking, because he’s not trying to push anything onto you,” Dugan said. “It’s very natural.”

By all measures, nearly a century into Mosley’s life, his career is at its zenith, but he remained humble as ever. Asked what he wanted to do next, he said he planned to keep making more wood sculptures. “People ask me, ‘What are you working on?’” he said. “I say, ‘I’m working on the same thing, just trying to make it look a little different.’”