Nico Williams Beads Trash and Treasures

Nico Williams, a beadwork sculptor and member of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation in Tiohtià:ke (the area now known as Montreal), transforms glass beads into a sort of velvety substance. His work, which he calls “soft sculpture,” references everything from bingo cards and dice to caution tape and plastic fencing—all in a manner that embeds beauty in the banal.

By re-creating common objects, Williams comments in a way on materiality and its role in separating Native activists from sacred sites transgressed by pipelines. He also explores how materials foster connection, from “rez aunties” making an extra buck at bingo halls to different kinds of cultural preservation. Williams balances barbs aimed at socioeconomic forces with humor intrinsic to the act of beading gambling cards and IKEA bags for display in museums he couldn’t afford to visit as a child—with the hope of inciting what he called “booming Native laughter that shakes windows down the street.”

First exposed to beading by elders on his reserve (as reservations are known in Canada), Williams didn’t take up the practice until after departing at age 16. But like many contemporary Indigenous artists, he found it difficult to access his culture in urban environments, leading him to YouTube videos for self-education. Later, as an apprentice to Algonquin artist Nadia Myre, he traded help rebooting a car for training in beadwork. In 2021, during studies for his MFA at Concordia University in Montreal, Williams began approaching his craft from a more technical mindset after accepting an invitation to join the Contemporary Geometric Beadwork research team, and he has taught workshops at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which he laughingly recalled mistaking for the Met and referred to as a “beading boot camp.” Of his work at MIT, he said, “I can’t do math—I just see.”

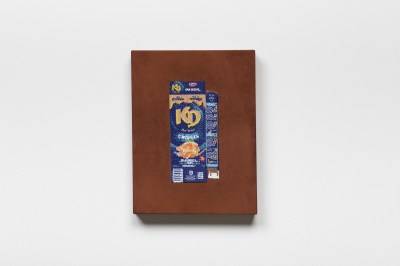

His experimental approach to beadwork is rooted in the principle of continuity. “We bead without knots,” he said. “The beads represent community—if you make a knot, that puts a knot in the community.” Early on, he explored his craft in small works like Starlite Variety (2021), a rendering of a shopping bag from a convenience store, and KD (2021), a yellow and blue beaded iteration of a Kraft Mac & Cheese box stitched into leather.

Nico Williams: KD, 2021.

Photo Paul Litherland/Courtesy Blouin Division, Montreal and Toronto

From these intimate consumerist effigies, Williams started making larger pieces mainly by accident after he intended to order 24 strands of orange beads but purchased 24 kilograms instead. That led to Barrier (2023), a large lattice of safety netting comprising orange bugle beads and three metal posts, and Biskaabiiyang | Returning to Ourselves (2023), a 73-foot-long hanging work fashioned like flaming caution tape. The pair of larger works evoke Inuit- and Métis-led “water protector” struggles in Canada around the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline and, for American viewers, the Oceti Sakowin–spearheaded Dakota Access Pipeline protests in 2016.

Such works earned Williams the $100,000 Sobey Art Award in 2024 and led to “Bingo,” a momentous solo show at Phi Foundation in Montreal (on view through September 14) containing more than 30 works grappling with land sovereignty, pecuniary difficulties, and trade in Indian Country. All the while, Williams continues to reckon with the dissonance between the stark reality of the reserve and the surreal privilege of consumer culture—an intersection he captures in his transformations of everyday objects.