Has the Art World Instrumentalized the Word “Activist”?

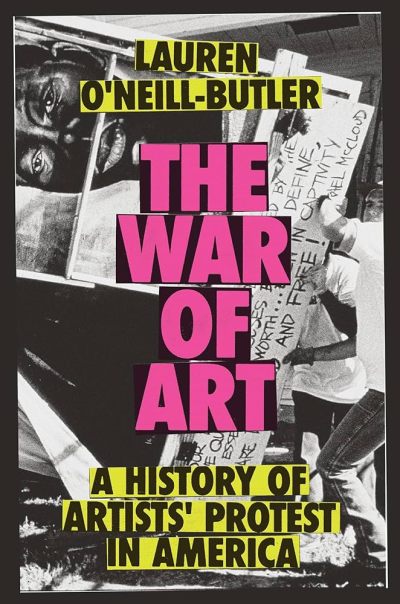

Courtesy Verso

Lauren O’Neill-Butler portrays the ten well-researched case studies that comprise her book on artistic activism, The War of Art: A History of Artists’ Protests in America, as qualified successes. The working class late 1960s Women Artists in Revolution group, for example, had a formative influence on the more renowned Art Workers’ Coalition, though the former’s emphasis on women-only spaces at times risked becoming, in Adrienne Rich’s words, “an end in itself.” The 1970s Black Emergency Cultural Coalition pioneered prison arts programs more humane than many of today’s versions, yet the group didn’t prioritize feminist concerns. The prominence of artist Rick Lowe’s 1990s Houston social sculpture, Project Row Houses, accidentally ushered in gentrification during the ensuing decades. Which is all to say that even when activist artworks manage to effect change, there are caveats.

O’Neill-Butler’s caveats establish the critic as a fair-minded chronicler of an artistic mode that can attract Pollyannaish claims regarding its impact. She states up front: “my argument is not that artists are the solution” to the “various ills of society.” “What I aim to show,” she continues, “is that they have motivated change and left a major mark.”

But this measured approach raises the question: why do artists persist in mobilizing art for protest when the odds are low their efforts will have substantial effects? An artistic intervention into a systematic problem can feel like putting a fresh coat of paint on a car whose check engine light is on. Here a picture emerges from the book, which covers the post–Civil Rights era: politically inclined artists recognize that their work may have long odds or limited agency, but they also recognize that change is necessary when conditions are trying. So they respond using the tools they know best.

Consider the prescient guerrilla media collective Top Value Television (TVTV), whose citizen journalism documented the 1972 Democratic and Republican conventions, during a contentious wartime US Presidential election. Their films, The World’s Largest TV Studio and Four More Years (both 1972), were broadcast across the country soon after the conventions and showcased vernacular perspectives unavailable in contemporary network journalism. O’Neill-Butler explains TVTV’s techno-utopic hope that “in the future everyone might have access to a portable video camera and that the resultant proliferation of images would quickly change hearts and minds,” but concludes with a dark caveat: “TVTV essentially paved the way for today’s deluge of verité footage on social media,” even if the group “could never have imagined the outcome.”

Harvard Art Museum die in, July 24, 2018.

Photo Tamara Rodriguez, Courtesy PAIN

This fascinating cross-era comparison highlights both the value and the limitations of The War of Art’s case-study structure. The book set out to connect the flurry of 2010s US artistic activism, which resulted in developments such as the New Museum’s staff unionization and Warren B. Kanders’ resignation from the Whitney Museum’s board, with that activism’s art historical antecedents. As the case studies unfold, the overarching theme becomes the ways that successive generations of artist-activists “sit on the shoulders of their chosen ancestors.” In consecutive chapters about two queer 1990s New York City collectives, fierce pussy and Dyke Action Machine!, O’Neill-Butler observes how their respective wheat-pasted poster campaigns not only prefigured New Red Order’s 2020s Indigenous agitprop but also drew on aesthetic tactics from the 1980s AIDS activist group ACT UP, which itself drew on 1960s and 70s civil rights and feminist movement tactics.

Yet O’Neill-Butler’s historical comparisons rarely delve into wherefores and whys. Instead, she seems content simply to point out how the formal tactics of one movement parallel those of another, sidestepping their differences in context. And she remains unwilling to theorize or define activist art. In the introduction, she contends, “it is generally not helpful to offer strict definitions of activism aside from that it is always a means to an end.” Instead, she believes that “the best way to answer these questions is not through theory or evaluative tools, but through case studies.” But the choice isn’t inherently either-or, as if theory and history were oil and water. Her reluctance to draw conclusions feel like missed opportunities to spell out takeaways from her research, given the considerable legwork she’s done. Potential caveats to her own project thus go unexplored, as when she asks, but doesn’t answer, if recent artists have “normalized” or “instrumentalized” the term “activist.”

Take, for instance, the separate chapters on ACT UP and on the artist Nan Goldin’s late 2010s Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (P.A.I.N.) organization, which serve as the book’s opening and closing case studies respectively. In the former, O’Neill-Butler describes an iconic 1988 protest photograph of artist David Wojnarowicz, recently diagnosed with HIV, wearing a jacket that says: “IF I DIE OF AIDS—FORGET BURIAL—JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE FDA.” She views the jacket’s text and other ACT UP slogans, such as “Silence=Death,” as examples of what she calls activist art’s “take, copy, distribute” logic. But when, in the final chapter, she describes the “direct cue[s]” that P.A.I.N. took from “ACT UP’s media-savvy actions”— “speak[ing] through the media, not to the media”; staging die-ins—she stops short of considering the two eras’ dramatically different media environments. In the 2010s, the question wasn’t whether activist organizations spoke “through” or “to” traditional media outlets but how cannily they spoke outside them, using social media to parlay viral attention into institutional credibility.

Edgar Heap of Birds: Genocide and Democracy, 2016.

ZEFREY THROWELL

In the TVTV chapter, O’Neill-Butler invokes artist Tania Bruguera’s concept of “political-timing-specific art” and quotes sociologist Stuart Hall on how such interventions can expose a culture’s “political, economic, and ideological contradictions.” The War of Art’s timing as a book inadvertently reveals similar tensions in our own artistic moment. The 2010s social media environment—which shaped so much recent discourse about the artistic activism that was this book’s impetus—looks quite different today, with many liberals retreating from X, and a general sense of fatigue with call outs and misinformation. Historical perspective is vital to understanding the present, and O’Neill-Butler does an excellent job chronicling recent artistic activism’s half-forgotten predecessors. But one moral of that history is to be careful what you wish for: even when it pans out, well-meaning citizen journalism or neighborhood revival art projects can have unintended downsides.