Rhea Dillon’s Oblique Portraits of the Black Diaspora

Within Rhea Dillon’s studio cubicle at the Whitney Independent Study Program (ISP), the artist and writer talked quietly about preparations for three exhibitions, opening weeks apart over the summer: her ISP group exhibition; a solo show at the Heidelberger Kunstverein; and a booth in the Statements section of Art Basel Switzerland. Famed for Marxist-leaning, theory-rich seminars, the ISP is a clear fit for the 29-year-old artist, who has temporarily transplanted from South London; her work engages a canon of Black and Caribbean historians, novelists, and poets including Kamau Brathwaite, Beverley Bryan, June Jordan, and Sylvia Wynter.

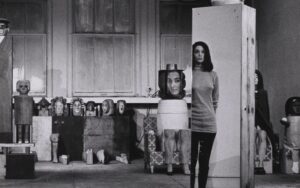

A second-generation British citizen with family in Jamaica, the artist often draws from her correspondence with the Caribbean, and critiques the sociopolitical ceilings inherited with diasporic identity. Sculptures such as Caribbean Ossuary (2022)—included last year in “Tituba, qui pour nous protéger?” (Tituba, who protects us?) at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris—suggest an immigrant’s aspirational longing for Old World luxury. The work presents a mahogany cabinet, echoing one owned by the artist’s grandmother, tipped on its back and seeming to float like a ship across the gallery floor. Within, items from a cut-crystal tea service (for when “the queen came”) hover atop a mirrored backing.

Dillon often produces sculptures like this one, crafting visceral portraits of postcolonial Black experiences from everyday objects, symbols, and language. Reflecting on her work’s territorial politics, Dillon said, “I think about land very physically now—soil, as opposed to geographies or trajectories,” citing American anthropologist Vanessa Agard-Jones.

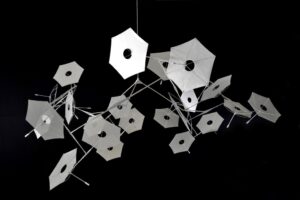

Dillon’s 2024 exhibition “An Alterable Terrain” at Tate Britain bridged the body and its diaspora through fauna. She presented a fragmentary Black woman, abstracted in a sparsely arranged constellation of sculptures representative of eyes, mouth, lungs, hands, feet[1] , and reproductive organs. In Swollen, Whole, Broken, Birthed in the Broken; Broken Birthed, Broken, Deficient, Whole—At the Black Womb’s Altar, At the Black Woman’s Tale (2023), dried calabash gourds are mounted on an angled plinth of sapele mahogany; some fractured, some whole, they stand in for womb, breasts, and vagina. Dillon calls out the commodity equivalence slavery drew between human flesh and wood, and underlines the parallel migrations of Black people and plant life.

Complementing her theoretical rigor with “poethics” (per the artist, borrowing poet Joan Retallack’s term), Dillon imbues her artworks with linguistic slippages and nonsensical evasions. Dillon’s writing favors elision and repetition, the latter shaping sections of her libretto for Catgut—The Opera, performed at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 2021. Pointing to photographs in her studio, Dillon explained this linguistic approach through a series of drawings central to “Gestural Poetics” at Paul Soto Gallery in Los Angeles last year. Originating when Dillon learned that “spade” was a racial slur, the oil stick drawings repeatedly rehearse the contours of the playing card icon, distorting the derogatory expression into a tree, a shield, or a pair of breasts. Looking over the recurrent symmetries of her drawings, the artist wondered, “Can I extend a definition? Or can I create a new definition through repetition?”