A Massive Diane Arbus Exhibition Does So Little

The era of Diane Arbus’s cold, classist gaze is dead. It belongs to an America that no longer exists and to an artistic school of thought that has run its course.

Her “freak” photographs of disabled, disfigured, and disenfranchised people she ambushed with a camera in asylums and hospitals were morally challenged when she made them between the late 1950s and early ’70s, and have only soured over the decades.

Now, with all the cruelty of the world right in our faces, we don’t need Arbus’s bleak style of confrontational art. We’re not looking to be shocked, dissociated, and dispirited so that we can be led to some somber conclusion about the brutality of living. We’ve got plenty of that on our screens or in our lives. Instead, we’d rather cling to every bit of humanity there is left and search for a kindness that’s rare to find in Arbus’s work.

Making matters worse, a major survey of the 20th-century American photographer, currently on view at Manhattan’s Park Avenue Armory, is riddled with questionable curatorial choices that seem intended to prevent critical discussion of Arbus’s legacy.

The curator behind these choices is Matthieu Humery, who installed Constellation on a labyrinth of black scaffolding, just as he did for the original 2023–24 show at LUMA Arles in France. With 455 prints spanning her 15-year art career (she started as a fashion photographer), this traveling exhibition is the largest Arbus retrospective to date.

This enormous exhibition was possible thanks to LUMA Arles founder Maja Hoffmann, who acquired printer’s proofs of the works from photographer Neil Selkirk in 2011. Selkirk, Arbus’s former student and collaborator, became the only person authorized to print from her negatives after her death by suicide in 1971. Hoffmann is a Swiss billionaire and an art collector who has a stake in her family’s Roche Holding AG, the world’s fifth-largest pharmaceutical company, according to Bloomberg.

Despite their volume and scope, reflecting several periods of the artist’s development, the prints are displayed in no particular order, neither chronological nor thematic. Visitors wander through a dimly lit maze of randomly hung photographs, carelessly bundling together distinctly different subject matter — a mélange of Upper Manhattan bourgeois couples, carnival workers, nudist hippies, and “woman impersonators” — with zero context apart from a terse timeline of the artist’s life on a wall outside the exhibition.

The result feels like a real-life doomscroll, where untitled photos of unnamed people with disabilities captured with deer-in-the-headlights expressions on their faces appear right next to handsome, well-composed actors and writers such as Jayne Mansfield, Mae West, Norman Mailer, and Germaine Greer. Absent are wall labels with useful information about these pictures: who many of these subjects were, how she met them, and what they thought of her photographs of them.

Humery, who once pronounced, “I do not really consider myself as a curator,” explained in an interview with the Guardian that he “tried to keep out any kind of narratives so that visitors create their own narratives.” This is either lazy, ahistorical curation or an intentional attempt to disorient viewers and distract them from inconvenient questions about Arbus’s art. It’s hard to form a critical opinion about a body of work when you’re overwhelmed by hundreds of photos without a morsel of context, even if many of the faces are familiar.

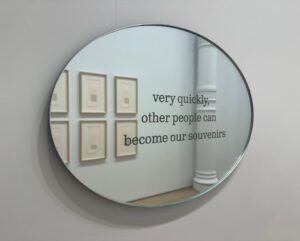

As I was grappling with these problems in Arbus’s work, I suddenly saw my reflection peering back at me inquisitively. For a moment, I thought I was hallucinating. A second later, I realized that I was looking at a tall mirror wall dividing the Armory’s 55,000-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall. The mirror partition was so convincing that Armory workers were positioned nearby to prevent visitors from colliding with it. On the face of it, this is just a cheap trick to make the show appear double its original size, manufacture some sort of voyeuristic play of gazing and being gazed at, or add a viral-baiting Yayoi Kusama-inspired infinity room effect to the show. But all this gimmickry ends up stunning and confusing visitors, rendering them as lost and clueless as a pigeon flying toward a glass tower.

Right around then, an Armory worker who saw me snapping photos of the show warned me that photography is prohibited for “copyright reasons.” A public relations agency later sent me sanitized installation shots that barely convey the experience of the show and do not allow discussion of specific photos. (I’m showing just one press photo here to give you an idea of the layout.) Why is this a problem? Because it indicates that the organizers want to control how the show is covered in the media. Humery, who promised to give visitors the freedom to “create their own narratives,” is in reality interested in just one narrative, actively preventing critics from presenting theirs. Because of that, I cannot show you what I saw and how.

Despite all the obfuscation tactics, one truth emerges from this heap of photos: a palpable class divide between Arbus’s subjects. Born to the affluent Nemerov family, owners of the now-defunct Fifth Avenue department store Russeks, Arbus was in her natural element in New York’s high society. In her photos, the rich look sophisticated and stately, while the wretched seem trapped in her gaze. But the rich, the poor, and the “freaks” alike look unhappy, even if some smile. The light of their eyes seems dimmed by Arbus’s troubled gaze, veiled by her dark aesthetic.

The late critic Susan Sontag identified this impulse as early as 1973, in a scathing essay in the New York Review of Books. “In their acceptance of the appalling, the photographs suggest a naïveté that is both coy and sinister, for it is based entirely on distance, on privilege, on a feeling that what the viewer is asked to look at is really other,” she wrote, adding that for Arbus, “both freaks and Middle America were equally exotic.” Sontag wrote her essay in response to an Arbus retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1972, which helped canonize the artist a year after her death. Since then, Sontag’s criticism has been largely pushed aside, and a market-backed orthodoxy has emerged around Arbus’s sensitivity toward the unfortunate and downtrodden. Never mind that she was reckless with the power of her camera and disregarded major ethical issues in her practice — her market soared, with some photos fetching over $1 million at auction.

It’s been a decade since the last major survey of Arbus’s work, hosted at the bygone Met Breuer on Madison Avenue in Manhattan. That show featured just about one-third of the photos now on view at the Armory. It’s disappointing that the organizers of the most extensive Arbus retrospective to date willingly abandoned their historical responsibility to continue the ethical debate over this major figure in American photography in favor of a spectacle-based “immersive experience.” They missed a precious opportunity to do justice not only to the people in the pictures, but to Arbus as well.