Alan Michelson’s Answer to the “Vanishing Indian” Myth

As a child, Alan Michelson often rode the T past sculptor Cyrus Edward Dallin’s “Appeal to the Great Spirit” (1908) outside the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). He was riveted by the statue’s grand horse and the powerful yet melancholy figure wearing a striking Plains Indian war bonnet. It was only in his 20s that the artist learned that he had been separated through adoption from his own Native heritage and Mohawk birth family in the Six Nations of the Grand River in Ontario, Canada. He soon learned that the Dallin sculpture he marveled at in childhood symbolized the nefarious “Vanishing Indian” myth, which cast Indigenous peoples as doomed to extinction.

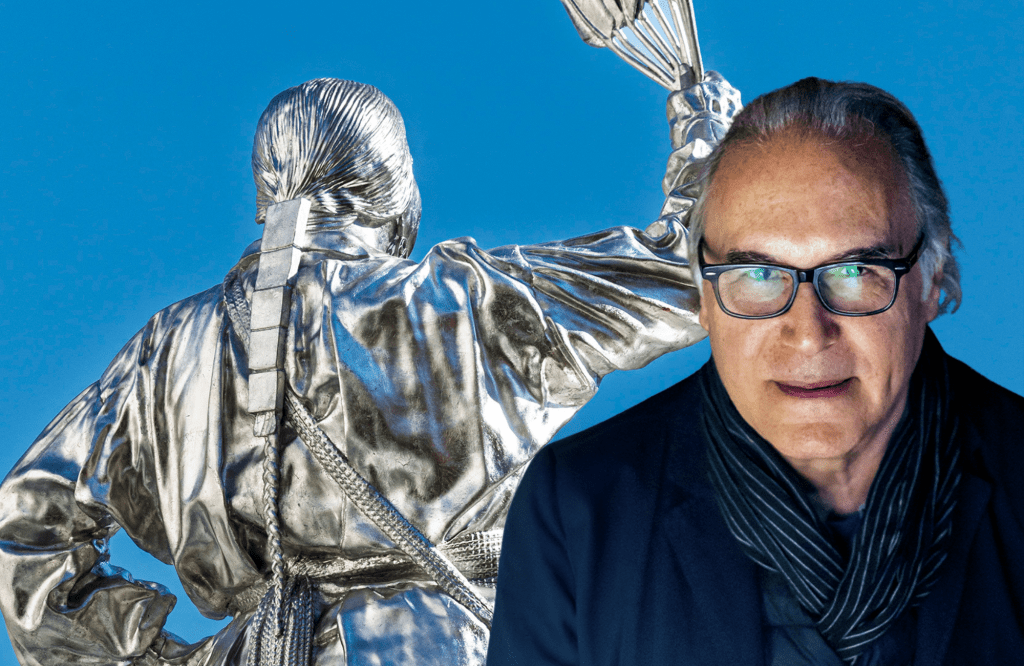

Last year, after four decades of reconnection with his Indigenous community, deep historical research, and the development of a highly acclaimed practice in video, installation, and public art, Michelson returned to the MFA to install his answer to the 1908 sculpture: two platinum-gilded bronze sculptures of living Native leaders who are Indigenous to the land now known as Boston. The gleaming forms of Aquinnah Wampanoag artist and activist Julia Marden and Nipmuc artist Andre StrongBearHeart Gaines Jr. stand proudly on the two large plinths on either side of the MFA’s entrance, resolutely toppling the myth that Indigenous peoples have disappeared from this land and honoring the vitality of Native communities today.

In this episode of the Hyperallergic Podcast, Michelson joins Editor-in-Chief Hrag Vartanian to discuss the process and inspiration behind this pair of works, titled “The Knowledge Keepers” (2024). They also discuss the dinosaur tracks on Mt. Holyoke that inspired the artist as a child, the reasons George Washington is known as a “Town Destroyer” in many Native languages, and how Michelson sees the land as a silent witness to history. We also talk with Ian Alteveer, the chair of Contemporary Art at MFA Boston, who walks us through the fascinating process behind “The Knowledge Keepers,” which is the inaugural installation in a series of monuments that will greet visitors at the museum’s main entrance.

Subscribe to Hyperallergic on Apple Podcasts and anywhere else you listen to podcasts. Watch the complete video of the conversation with images of the artworks on YouTube.

A full transcript of the interview can be found below. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

AM: I was exposed at an early age to dinosaur tracks. My mother enrolled me in my first drawing class when I was seven years old. And from the place where she dropped me off on the street, you walked up a driveway that was paved with some of the fossilized stones —

HV: No way. Wow.

AM: — with dinosaur tracks. So I would literally time travel. As soon as I got out of the car, I’m like thousands of years in the past. And my imagination was just set off like a fire. And I was a curious guy. I went for it hook, line, and sinker. So I think that that’s sort of the foundation of some of my time travel.

I guess I think of the land as a sort of silent witness. And so then if I pull up some things, then maybe I’m the mouthpiece or I’m an advocate. Sometimes I feel like I’m an advocate or a speaker for things that can’t speak.

HV: Hello, and welcome back to the Hyperallergic Podcast. You were just listening to the voice of artist, Alan Michelson, an artist and Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, who’s based here in New York City. As a child growing up in Boston, he’d always been fascinated by Cyrus Dallin’s “Appeal to the Great Spirit,” which is a sculpture of a Native warrior on a mighty horse that’s been outside the museum since 1912. It’s a beautifully done work, but illustrates a nefarious myth called “The Vanishing Race.” The idea that indigenous people in America had completely lost the battle with their colonizers and would soon disappear. Many years later, with years of work as an acclaimed artist under his belt, Michelson was commissioned to sculpt his answer to that sculpture, and that’s what we’re here to talk about.

“The Knowledge Keepers” are a pair of sculptures unveiled in late 2024, modeled on two living community members who are indigenous to the Boston area. Over a century later, they gleam with a silver finish, a powerful response to the myth of “The Vanishing Race” that undergirds the “Great Spirit” sculpture nearby. In this episode, we’re going to talk all about his story from reconnecting with his indigenous heritage after years of being separated from his birth family through adoption, his wide-ranging site-specific public art practice, what it means to be Indigenous from the northeastern United States, why George Washington and many other U.S. presidents are called “town destroyers” in some Native languages, and the place he feels most at home; here in our beloved New York City.

We also visited with curator Ian Alteveer at the MFA in Boston, who told us about the process behind the new addition to the museum’s facade, which coincidentally is also part of the inaugural Boston Public Art Triennial that starts in May 2025 and continues until October. I’m Hrag Vartanian, the Co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of Hyperallergic. I think we have a lot to cover and to talk about. So let’s get started.

HV: Welcome, everyone. Today, we have Alan Michelson. Hi, Alan. How’s it going?

AM: It’s going well.

HV: I’m really excited to talk to you about your project that’s currently up at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, “The Knowledge Keepers.” Congratulations, by the way.

AM: Oh, thank you.

HV: We met each other about 10 years ago at the indigenous New York conference that you helped put together. And I still think about that conference because it was a really great opportunity to open the eyes of a lot of us to an Indigenous history here that has been hidden. And I bring that up particularly because so much of your work is about those layers of history that are often erased, that are often ignored, that might be repurposed in different ways and also just different perspectives. And that’s one of the things I appreciate about it. And in this case in Boston, you’re responding to a specific sculpture that you remember from your own youth as well as through the years?

AM: My interest in history goes back to childhood. And when we moved to Boston, when I was nine, my stepsister took me on the Freedom Trail, which you’re probably familiar with.

HV: Yep.

AM: It’s marked by a red line and it goes past these nationally significant historic sites. But what impressed me the most at that age was a very modest monument that wasn’t even visible above street level. It was a circle of cobblestones, about a dozen feet in diameter, that was marking the site of the Boston Massacre from 1770, one of the catalysts of the American Revolution. And I remember standing on those cobblestones and just thinking, “Wow, people were killed here a couple hundred years ago.” And it was electrifying somehow through the soles of my feet. And that ended up being a sort of basis in a way for a lot of the work that I do, which is site-specific and raising up histories that are not visible at surface level. So MFA Boston was one of those sites from my childhood. And the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, was my first sort of encyclopedic museum as a child.

HV: We never forget those, do we?

AM: Yeah, we don’t.

Ian Alteveer: Hi, I am Ian Alteveer. I am the Beal Family Chair of the MFA Boston’s Department of Contemporary Art. When I arrived at the MFA Boston in the fall of 2023, one of the first activities and programming areas that I needed to tackle was what to do with these two plinths that were at our main entrance on either side of the stairs. They had been occupied for a number of years by two rather nondescript cast iron urns that were soon to be removed. And all thought that this would be an amazing opportunity to ask a living artist to contribute something special to our entrance. We conceived of the project as an annual –– or biannual, or something in the middle there –– opportunity for an artist to make a really big impact in a space that is our first point of entry for the public. A fantastic colleague, Marina Tyquiengco, our associate Curator of indigenous art in the Department of Art of the Americas, put Alan’s name forward.

The team all thought that Alan would be an amazing choice for this first go round, for a variety of reasons. He spent time from about age eight to about age 18, riding the T back and forth every day on the way to school, looking at the museum, looking at the sculptures in front of the museum. And then he returned at some point to go to art school here as well. So that was important to us too, that there was some connection to the city. And also, of course, because of those connections, he had quite a sophisticated take, I think, on the sculpture that’s there by Cyrus Dallin.

AM: My memories of that sculpture go back to nine years old. I’ve seen it in all kinds of weather and all sorts of ages and all sorts of understandings of art. It’s called “Appeal to the Great Spirit.” And it’s a plains rider, nearly naked, but wearing a very stereotypical war bonnet.

HV: But also generic moccasins.

AM: Generic moccasins. He’s on a stilled horse. It’s a very still sort of monument. And it’s striking in its own way. I mean, Cyrus Dallin –– like many of the sculptures of his generation, Augustus and Godens and a lot of those –– they were skilled sculptors. And so the thing about the “Great Spirit” is that it’s not without appeal.

HV: Right.

AM: So that sort of gives it a certain power. But I’m not sure that that statement is really relevant today. It was taking a humanitarian stance, or I think he thought it was taking a humanitarian stance, at a time when Native people had been reduced and had been decimated. And it was implying that this could be the last of a people.

HV: I mean, he’s playing with the Vanishing Indians trope, right?

AM: Absolutely.

HV: Which was super, super prevalent then. And it was almost like it was an assumption that Native people were going to disappear.

AM: Yes. And thank God it was proved wrong.

HV: Right. Yeah.

AM: I know from being a Bostonian that Bostonians know how to read that sort of era sculpture. It’s all around. It’s all in the public parks. And I just thought that if I could do a different version of that, that would hold its own in terms of look and in terms of materials, — it’s platinum-gilded bronze — that they would be able to be in better conversation with that and hopefully change the atmosphere in the front of the museum.

HV: Do you remember the first time you saw the “Great Spirit?” Did you feel like, “Hey, representation”? Or was it, “What is this?” What was that kind of relationship?

AM: At nine, I was not that sophisticated, so I just was like, “Wow.” I loved horses and that sort of romance, the American West, all that stuff.

HV: That’s how it functions, right? It does appeal to those different things.

AM: Exactly. It was the hit of the Paris salon in 1909 or something, which is why it ended up there.

HV: The thing about that sculpture, too, is that it’s reminiscent of other images of the “Vanishing Indian” trope, right?

AM: Yes.

HV: And it was actually the most optimistic one, in a weird way. I feel like most of them are really, really depressing. They’re very defeated. Do you think there’s something unique about that sculpture that also may have appealed to you?

AM: Yeah. I mean, I think it’s the body language, if you could say that. The pose of the sculpture is less of that stereotype of the dying Indian, but I was thinking about it. There’s something sort of Christian, it seems to also —

HV: You’re right!

AM: — enter into it.

HV: That’s such a good point.

AM: It’s like a crucifix. But in usual crucifix paintings, the head of Christ is always bowed down looking like that.

HV: Right.

AM: There are a few that are like this [gestures with arms outward and head up]

HV: That’s right.

AM: And I was thinking that that might’ve inspired him in some way.

HV: You know what that brings up for me too? That’s also this image of like, “Lord, why have you forsaken me?”

AM: Exactly.

HV: Do you know what I mean?

AM: That’s what occurred to me.

HV: Oh, I just got a little chill…

AM: Yeah.

HV: That is kind of creepier than I thought.

AM: Yeah, yeah.

HV: Because there’s kind of this…ooh.

AM: Well meant, probably.

HV: Yeah.

AM: I mean, I don’t think it should be junked. I don’t think it should be hidden. But I do think mine should stay there.

HV: Yeah. So let’s talk about “The Knowledge Keepers.” There are two sculptures of a local Nipmuc activist.

AM: Andre StrongBearHeart Gaines, and also Julia Martins. She’s an artist and also a community leader.

HV: Right. So both of these figures, one male, one female, are sort of at the entrance of the museum. And they’re also made of bronze, and then they’re covered with platinum.

AM: They’re gilded, yes.

HV: Gilded with platinum, apologies.

AM: Yes.

HV: And they have this kind of really radiant energy at the entrance. Tell us a little bit about your thinking behind this and a little bit about how you saw them in relationship to the entrance, the sculpture to the public.

AM: My models are live, thank goodness. Very accomplished people. Very important to their communities. They are Knowledge Keepers, and so they already are radiant. So it was posed like how do I capture that? So part of it was pose. Like, I knew I wanted Julia to be holding up that eagle feather fan. I also had seen images and seen talks by Andre StrongBearHeart Gaines. And so I just thought that would really counter the sort of passivity or the supplication, the sort of pleading plaintive thing of the Plains figure. So part of it was just wanting that life to come through, and then the material. So what should it be? And radiant substances have a certain sort of metaphorical and metaphysical significance to Northeastern Woodland people. So that glow is something that’s almost like medicine. Traditionally, it was from shells from wampum, but also there was Native copper in the Midwest that was traded. And then when silver came with the colonists, that became a big thing. So I was trying to riff on that and extend it. Turns out that silver leaf tarnishes almost immediately.

HV: Anybody who has silver knows that that’s a problem. [Laughs]

AM: Yes, yes. Well, outdoors, it’s even worse.

HV: Even worse.

AM: So we went with platinum, which is the most stable, the most durable of all those substances. That would be metals used for gilding. Not cheap.

HV: You bet. You got it in before the tariffs though. [Laughs]

AM: Yes. But it’s also forward-facing. It has futuristic associations as well.

HV: Absolutely. You definitely get that. There’s this sci-fi kind of aspect. It’s like space travel or something. Do you know? There’s something very futuristic about those images. And then also I think with the “Great Spirit” sculpture, it’s sort of like it changes the sculpture because he’s not alone anymore and he’s flanked by these two figures.

AM: Yes. In fact, if you stand at a certain spot and his upraised arms, it’s almost like the figures are in his hands.

HV: Oh, no, I got that immediately. And it’s sort of like… I loved how it almost felt like this person wasn’t alone anymore.

AM: Appeal answered.

HV: What do you think of the choice of making it silver? And I’d love to hear your take on how you think it completes the work or maybe complements other parts of the museum.

IA: It’s a great question. We went through a lot of possibilities with the finish for those particular sculptures. I think Alan is always really interested in color and in the materiality of things. It seems to play an important role, color especially, in a lot of past works. Color and reflection, I’d say. Once a sculpture is cast in bronze, you can choose to use a patina. Or, you could paint them, which kind of tends to dull some of the sharp edges of a nice bronze cast. Or, you can gild them. And Alan had thought about a metallic finish. Bronze itself is metal, and he landed on platinum in a really interesting way. He was researching this a lot and read some studies from anthropologists and archeologists who said that platinum is really an indigenous metal. It’s something that indigenous peoples in South America first discovered and used in all kinds of ways. What’s also cool about platinum is that it is one of the most incorruptible metals.

HV:Wow.

Ian Alteveer: So it is really protective. And as a result of that, it’s used for all kinds of applications and kind of space-age technologies, and it has this amazing, beautiful kind of otherworldly sheen. And so rather than being reflective, it is more shimmering. Right?

HV:Yeah.

IA: And so they have this beautiful, almost lunar quality, especially at night. And that spectacular gleam also is a protective coating. So Alan is kind of protecting these amazing people. Folks who pass by the museum, who are used to seeing every day, maybe the same old sculpture out there are now seeing something different, something spectacular, something glowing from the inside almost. So that’s also special too.

HV, to AM: Let’s talk a little bit about your own past. And I know your family’s from Six Nations, a reservation in Southern Ontario. And as I told you, previous to our conversation, I’ve been there. Because I grew up in Toronto, and so I remember going to the Six Nations, and it being the only reservation maybe that people in Ontario even knew, frankly.

AM: Yes.

HV: It was very popular. The powwows were very well attended, right?

AM: Yes, yes.

HV: And there was a presence in the community in a way that I think very few other Native communities, at least in Southern Ontario, had. How would you characterize it?

AM: I mean, there are few reservations or reserves east of the Mississippi. You know, Andrew Jackson took care of that. So it’s only people like yourself who are, let’s say, Torontonians, who are conversant with Six Nations and the powwows. There are some mini-reserves in New York, and the people around there are familiar, but most people just think Native people are only in the West.

HV: It’s also interesting because scratching the surface of the Northeast, there’s always something Native. Right?

AM: Yeah.

HV: That contradiction is very prevalent here.

AM: Well, there’s still lots of place names.

HV: Yes.

AM: So that’s, I think, what most people are familiar with, and then they’re familiar with the stereotypes.

HV: So in terms of your own sort of past, do you want to tell us a little bit about growing up? Where did you grow up and what was your relationship with your own communities?

AM: I have a bit of a complicated background. I was part of that probably 30% of my generation who were separated from their Native families through adoption. And so I grew up first in Holyoke, Massachusetts, and then our family moved to Boston. So I wasn’t even aware of my Mohawk background until I was in my 20s.

HV: Wow. So tell us a little bit, if you don’t mind sharing, what were the conditions for that adoption? We talk about family separations, but I guess people don’t often understand what that actually meant for people’s lives.

AM: There are all forms of Native removal, and I think that was trying to be the most benign. It was trying to answer a need. So in my case, it was a voluntary adoption. But then again, you could say that the position that colonialism had left my Native mother and family was not conducive to ––

HV: Oh, no. I would argue that it definitely, like those conditions like poverty and other things, those are structural, right?

AM: Yes. But adoption is age-old.

HV: Yeah, absolutely.

AM: It’s not confined to this. But I think that probably like many adoptees, you want to know.

HV: Absolutely.

AM: And you’re not told. In fact, there are laws in Massachusetts protecting all that information. So I was fortunate, being able to do that and to reunite with my Native family.

HV: I think just so the audience thinks about it too. I mean, could Native families adopt white children?

AM: I don’t think so.

HV: Yeah, that’s what I mean. So that’s what I’m saying, like, where the structural violence of the system is actually much more ingrained.

AM: Yeah, it was asymmetrical, for sure.

HV: Right, exactly.

AM: Yeah. Like everything.

HV: Yeah, absolutely.

AM: It represents power relations.

HV: Absolutely. Yeah.

AM: And it was in many ways. I mean, I was raised in a great loving family and was really well-educated in public schools and so forth. And I’ve tried to use that education to not only learn about my culture before I was even immersed in it ––

HV: You mentioned in your 20s is when you realized you had a Mohawk heritage. I mean, I would assume that there would be an amount of shock in that reality.

AM: It was mind-blowing.

HV: Yeah.

AM: Yeah. Just think of it, to be part of a relatively small population and then wanting to understand it, embrace it, and live in it, which is what I’ve been doing for 40 odd years.

HV: So when you first heard that, what impact did it have on you? Was it like, “Why was this hidden from me?” Or was it more of a, “Wow, this has just changed the ground beneath my feet?”

AM: Yeah. I mean, I always felt connected to the land here, and that was one of the first things that hit me. I am connected in some very powerful way that was subliminal. So I can’t say that was the biggest thing, but then it was all curiosity. Like, “How do I approach this?” I needed to learn. And so I’ve had some amazing teachers and mentors along the way. Members of my family from Six Nations, members of their larger social networks. Jimmy Durham was an important figure for me ––

HV: Absolutely.

AM: Edgar Heap of Birds. There were a lot of influences then.

HV: That generation, yeah. Did it change the way you saw certain objects? I wonder?

AM: It changed the way I see the world. And in fact, I think in my work, formats are important to me. And one of the reasons I like panoramic format and use it is because there’s not one vantage point. It invites multi-perspectives, and it invites dialogue in relation, because like some of the ones I’ve made are pretty big.

HV: Huge.

AM: So you end up being in dialogue with it rather than just sort of like a small picture where you just sort of gulp it and move on. And that’s one of the reasons I also like time-based art, is that things move. There’s not a story, there’s not a narrative, there’s not a sequential narrative in my work. Time is quite embedded in it.

HV: Absolutely.

AM: Yeah. Yeah.

HV: I want to talk about the piece “He(a)rd.”

AM: Oh, sure.

HV: I love that piece.

AM: Yeah. Yeah.

HV: So you did that in the UK, I believe. Correct?

AM: Yes. In 2005.

HV: And what was the name of the space you did it in, if I remember?

AM: It was Compton Verney.

HV: Compton Verney. And what you did there was you had the sound of a stampede.

AM: Yes, a bison stampede ––

HV: A bison stampede that visitors to this beautiful room designed by this neoclassical architect.

AM: John Adams, yes.

HV: John Adams.

AM: Yeah.

HV: You know, you hear this buffalo, this bison stampede through this sort of pristine white space, or at least they hear the sounds of it. How would you characterize the piece?

AM: It’s a beautiful space that John Adam designed. It’s marble and it’s very classical looking. And outside, I don’t know if you saw many pictures of it, it’s an invisible work in a way. It’s sound work. There were just speakers on either end of this thing, but I had arranged the sound, so it sounded like they were in the distance and then coming as you get closer to the other speaker, and then vice versa. So it would just go back and forth all day.

[Stampede sounds from Alan Michelson, “He(a)rd,” (2005)]

AM: There were these bucolic sleeping cows that were just outside.

HV: Did they freak out?

AM: No, they just were grazing away. So that was a cool piece.

HV: Oh, so that adds another layer, almost like this domestication, right?

AM: Yes, yes.

HV: You know, like from the bison to these cows is kind of like—

AM: Yes. A European cow versus an American cow.

HV: Right. Yeah, I love that layer. That’s so great. I’ve noticed this one pattern in your work, like your sculpture in Richmond, Virginia, where there’s a relationship to this “older figure” that may have been pivotal in the history of America, in the case of Virginia, where it’s like a building designed by Thomas Jefferson.

AM: Yes.

HV: Right? And in this case, about this room that’s sort of designed or in the case in Boston where you’re responding to this older sculptor.

AM: Yes, yes.

HV: Tell me a little bit about that relationship. What is it that really excites you and what ignites your imagination there?

AM: It was prevalent this summer when I was able to show at the Thomas Cole House.

HV: Another figure, right?

AM: Yes. You could say he’s not only the father of the Hudson River School, but maybe of American painting in general.

HV: Landscape painting, for sure.

AM: Yes. And so you’re right. Maybe that model of not starting from scratch, but starting from some sort of conversation with something that’s preexisting, and then working from the present and wanting to project something into the future. But I was exposed also at an early age to the dinosaur tracks ––

HV: Oh, I love that story that.

AM: –– in Holyoke. Yeah.

HV: Those are the first recorded, or at least that publicly known dinosaur tracks, right?

AM:

Yes, yes.

HV: And that’s in Holyoke, Massachusetts.

AM: Yes, yes.

HV: That blew my mind, I didn’t realize that.

AM: A couple of miles from where we lived, and there was this sort of folk sculpture of a dinosaur that I just loved. That was the first sculpture I really loved.

HV: Right. It was like a roadside attraction.

AM: Yes, it was a roadside attraction.

HV: Right, right.

AM: But the tracks themselves were amazing. Kids love dinosaurs. My mother enrolled me in my first drawing class when I was seven years old. I was the youngest in the class. From the place where she dropped me off on the street, you walked up a driveway that was paved with some of the fossilized stones —

HV: No way. Wow.

AM: –– with dinosaur tracks. So I would literally time travel. As soon as I got out of the car, I’m like thousands of years in the past. And my imagination was just set off like a fire. And then the house itself was like this Addams Family spooky sort of mansion with old oriental rugs. It’s sort of dark. It had things like arrowheads, then it had Hudson River paintings. It had a weird big music collection. It was a cabinet of curiosities.

HV: [Laughs] Right, right.

AM: And I was a curious guy. I went for it hook, line, and sinker. So I think that that’s sort of the foundation of some of my time travel.

HV: I mean, it makes sense because you do a lot of works where there’s the impressions of objects, right?

AM: Yes.

HV: Which reminds me of the way you’re talking about the dinosaur tracks or the fossilized, where you’ll embed them in these stones or the piece you did at Wave Hill where you do the different vegetables or casts that appeal almost like rosettes or flourishes and other things in the room.

AM: That’s great. I never related those two. Yeah. Yeah.

HV: I think it feels very connected.

AM: Yeah, it is very connected. So the idea of something being a tracker, a trace, that is standing for an absence.

HV: Right.

AM: And with dinosaurs, it’s very absent.

HV: Absolutely

AM: I mean, extinct.

HV: Absolutely.

AM: But you can look at any site that way as there are traces, and some of them are no longer there. Some of it is just information that… So one can dig in a site without physically touching it.

HV: Absolutely.

AM: That’s part of my process. But I ––

HV: And time travel at a site.

AM: Yes. And that’s what I do, and ––

HV: I know that’s exactly what you do. That’s why I bring that up. I mean, the time traveling.

AM: Yeah. It’s a habit, and it’s one that serves me well in my work. Sometimes I get these feelings. Honestly, my first major public artwork was the Collect Pond piece, “Earth’s Eye,” in 1990.

HV: That’s amazing.

AM: And ––

HV: Talking about the hidden history of a site, we have here in New York, which is the Collect Pond, which used to be around where the tombs are.

AM: Yes, exactly. Yeah.

HV: Right there. Which is ––

AM: The Court District.

HV: For those of you who are not from New York, the tombs are where the courts and the prison are in Lower Manhattan. So that’s a very symbolic site.

AM: Exactly. And you couldn’t make this up because entombed underneath all that was a living pond, a spring-fed, major pond. Something that was probably half the size of Walden Pond and is deep and is pure. That was just in the way of all that mercantile, extractive activity.

HV: Right. And you also mentioned the fact how they sort of made it toxic. Right? It’s not like it disappeared out of nowhere. They just literally made it toxic with all the stuff they’d pour into it. The oils and whatever.

AM: They poisoned their own water supply. It was insane.

HV: Yeah. Which is so bizarre, right?

AM: Yeah. It was insane. I mean, you think about who allowed that, what sort of governing body allowed that. But anyways, there’s a karma to it because they thought they could maybe develop it as new land. And they had this scheme to do it, to make it a residential fancy place called Paradise Square, but they had neglected to remove the vegetation when they buried it, and all of it started to rot and stink and sink.

HV: Oh, wow.

AM: So it became a stinking mess, as did the slow little stream that they turned into a canal; that’s how they drained it to the Hudson. And then the canal became smelly and they buried it under Canal Street.

HV: It became Canal Street. Exactly.

AM: Yes. But just the thought of this beautiful pond and wetlands that was supporting so much diverse life and was a Lenape site because there was a large midden on the Western shore where Tribeca is now. A huge midden, big enough so that the Dutch named it. They named that area Colchoke, which meant “shell point” or “chalk point.”

HV: Got it.

AM: And they were extracting those shells. I mean, in that case, they just bulldozed them in their 19th century way. That was part of the landfill. But I think of that, I think there’s just all those oysters. That’s a kind of archive down there too, of thousands of years of generations and generations of Indigenous people eating and dining on oysters and shellfish right there.

HV: Right. Yeah. And even thinking of the fingerprints they must have left. Think of the different worlds or the activities that happened around these things. And now of course, in New York, they’re replanting oysters, right?

AM: Yes, yes.

HV: It’s sort of ironic, right? Now it’s like there’s this big movement to bring in all these millions of oysters to clean the waters of New York and return them to a more natural state.

AM: Yes, yes. Well, are you familiar with my midden piece?

HV: Yes. Yes.

AM: So that was a partnership where I was lucky to collaborate with the Billion Oyster Project.

HV: That’s right. That’s the project. That was the MoMA PS1 piece. Correct?

AM: It’s great. Yeah. I mean, one oyster can clean up to 50 gallons of polluted water.

HV: Isn’t that crazy?

AM: Yeah, it’s amazing. So using a nature-based solution, to me, is brilliant. It should be embraced.

HV: Yep.

AM: Yeah, so upcoming for me is a project with more art.

HV: Nice.

AM: So I’m sort of their commissioned artist for next year. And I’m hoping to work again with the Billion Oyster Project. I have another oyster project in mind.

HV: Love that.

AM: One of the things I like about casting is that it’s like what you see is what you get. It’s in many ways the most true form of representation that you can make of a three-dimensional object.

HV: Absolutely.

AM: Sometimes I feel like I’m an advocate or a speaker for things that can’t speak.

HV: Oh, that’s powerful. That’s powerful. And also, I think the casting also, coming back to the notion of time, freezes something in a moment.

AM: Absolutely. I’m a fan of this brilliant British psychoanalyst and author, Adam Phillips. And just in passing, at the end of one of these conversations, he just said something like, “Art monumentalizes life, it stops time and invites space for reflection.” Something like that. And I think that’s exactly what it does.

HV: Spot on.

AM: Yeah.

HV: Yeah, I think that’s really powerful. You also write, you make video…

AM: Yeah.

HV: How would you connect these all together in terms of your general artistic practice? characterize thatfor people?

AM: I think that what you pulled out about casting, I’m trying to, within this massive subjectivity that is art, have something that rings true, have something that’s… There’s a documentary aspect to my work, and yet there’s enough that separates it from fact or the usual forms, typical forms of documentary. So I try to mix that with a lot of formal experimentation and experimentation with materials. In my video work, I’m trying to give video some thickness because it’s considered this two-dimensional thing.

HV: Yeah, yeah. Well, I would even say texture.

AM: That’s a better word, maybe.

HV: I feel like there’s texture in the video pieces you create that both makes the image more powerful, but also sometimes obstructs it a little bit. Like, there’s this kind of almost like a grain.

AM: There’s a contest actually.

HV: Yeah.

AM: Yeah, I sort of set them into relation, and the relation sometimes ends up being a conversation, but one that maybe one can drown out the other sometimes in it. Like, with the midden piece, I projected extreme panoramic video, like 30 feet by six feet or something like that, onto three tons of shells that were laid out in a wedge-shaped thing.

HV: And it was the waterfront, was it? Which waterfront was it? I’m trying to remember.

AM: It was formerly really good oyster grounds that was on the very polluted Newtown Creek.

HV: That was at Newtown Creek. That was ––

AM: Yeah.

HV: Yes. Right up here actually.

AM: Yeah. And the Gowanus as well.

HV: Yeah. Yeah. So Superfund sites.

AM: Superfund sites that were once beautiful sites of oyster ––

HV: And those who may not know Superfund are super polluted sites the government designates for special funding for cleanup.

AM: Yeah. So in the case of the midden, first of all, you could see it from three different levels.

HV: Right. So this is in the MoMA PS1, that sort of like that hall kind of atrium space, the taller duplex space where there’s often only one work, like a large installation work.

AM: So from the main floor, you could look down at it and it flattened out because you’re looking down. But then as you got to the basement and then sub-basement, and as you got really close to it, I noticed that the video seemed to harden, and the shell seemed to liquefy.

HV: Interesting.

AM: You know what I mean?

HV: Yeah.

AM: It’s like the sort of flowing colors of the video on the shells made them less hard, but it hardened the video, if you know what I mean.

HV: Yeah, yeah. I get that.

AM: Yeah. I used to paint actually that way, where I would cover my canvas with materials that I collected from the site. Could be twigs and little things and leaves and stuff. And I would then paint something that was figurative over that. And so there’d be a little contest. I got that from Kiefer, just a contest between the material itself speaking and then the other. And so there’s a way in which the video, even if it’s not narrative, has a narrative quality to it. And there’s a way in which shells or Turkey feathers are mute, but very expressive of nature. So it changes that there’s something declarative maybe about the video and something that’s just like a drone about the object that I’m projecting onto. But then I got into things that are a little more complicated, like a human face, like George Washington’s.

HV: Ah, let’s talk about that one.

AM: Yeah.

HV: But first I just want to clarify for Anselm Kiefer, for those who may not know the German artist, because he works a lot with memory too, which really connects with yours.

AM: Yes.

HV: And I mean, the memory of genocide specifically, he often works with, right?

AM: Yes. He was an important artist for me when I was moving out of abstraction into figurative work. In fact, he was probably the impetus for it.

HV: He’s your bridge. I like that.

AM: He was. Yeah. Yes.

HV: I love that. So let’s talk about this piece, because the George Washington bust, I think it’s an incredible piece. You bring up the history that in the Mohawk Nation, he was called “town destroyer.”

AM: Yeah.

HV: Or is it a Haudenosaunee word? Remind me, please.

AM: He inherited a title from his grandfather who was the first upon whom the local Natives, I think they were Susquehannocks, that he murdered, so ––

HV: Down in Virginia?

AM: Yeah. Or around that area.

HV: Yeah.

AM: There were wars in the late 17th century. I think that it probably translated slightly differently in all the different Nations’ dialects and languages. Even at Six Nations, if you listen to my thing, you’ll hear different pronunciations of it.

[Music plays, various speakers recite “Hanödaga:yas” in the audio of Alan Michelson’s “Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer)” (2018)]

AM: That was the first time, really, that I’ve used the figure in my work. A lot of my work is about what human beings have done. It sort of shows results, but it doesn’t show the people.

HV: And traces.

AM: Yes, traces. Exactly. But it’s like the part standing for the whole. It’s not typically figurative in that way. So that was the first time that I sort of got into that. But this idea of history as a projection, that also occurred to me. Right?

HV: Right.

AM: It’s a projection often of a fantasy, often of what I would distinguish between history and heritage. I think, okay, heritage maybe can be a neutral term. The way I’m meaning it though, it’s very inflected history. It’s a very biased history. It’s sanitized history. And so our image of George Washington, which is in our wallets, you know, everywhere ––

HV: Yeah. Yeah. Everywhere.

AM: –– there’s really such an icon to take the liberty of, “Give me liberty.”

HV: Yeah. Yeah.

AM: That was a step for me. It’s not unlike, in a way, dealing with the Dallin in front of the Museum of Fine Arts you saw.

HV: Yeah, absolutely. I see the connection directly.

AM: Yeah. Yeah.

HV: And the thing about that Washington piece is, again, this term, “town destroyer,” it sort of changes our idea of who he was. And it reminds me of when I visited the Seneca Nation in Western New York. Like, when they talk about JFK, they have a whole different history from the understanding than mainstream America. They see him as negative, because he took their land, you know.

AM: Yes.

HV: And it reminded me of that, where Washington then becomes this figure that has been transformed. Like, no matter what Houdon did, and tried to glamorize him into this almost ancient Roman-like figure, you’ve sort of projected onto him this other history.

AM: Yes.

HV: These maps, these different traces of violence that have brought up… Now, do you think that that piece…how would you connect that to your interest in sculpture in space and time?

AM: I think that in a way, the bust is a trace as well, because it’s based on a cast.

HV: Right.

AM: But I wanted to just get into his title, “Town Destroyer,” a little bit, because every subsequent American president is known that way.

HV: Oh, I see.

AM: Yes.

HV: So all of them. So the name started there, but then it sort of…

AM: Yes. Yes, they inherited. So that was also prevalent. Even around New York, there was a Dutch governor named Corlear. Corlear’s Hook was once a place on ––

HV: Oh, of course.

AM: Yeah. So all the subsequent governors we called Corlears.

HV: You’re kidding.

AM: Yeah. So it stuck.

HV: Right. Right.

AM: And in the American Revolution, the revolutionaries were known as the Bostonians.

HV: Really?

AM: Yeah. So there was a sort of consolidation of these sorts of things. And if you think about it ––

HV: I love that because it also pokes into the mythology, right? It pokes it through it, and sort of gets to a different perspective, which is like your kind of work is on in general. Apologies, go ahead.

AM: Yeah. No, no, that’s true. This idea of presidents as town destroyers, there have been few that haven’t destroyed some towns, and that’s been turned into sort of this glorious American history. But most of it is pretty bad actually.

HV: Yeah, absolutely. And even when Natives fought the American Revolution, they didn’t really get anything.

AM: Yeah. I mean, the Tuscarora and Oneidas, some of them sided with the Americans, and their land was ––

HV: Taken as well.

AM: –– taken as well. Yeah.

HV: Yeah. I’d love to talk a little bit about place and site, which seems to be very important to you.

AM: Yes.

HV: What is it about that? Is it a positionality? I mean, I know we’ve talked about landscape as being an important part of that, but what is it about place that maybe roots you in something or… What is it about that idea for you?

AM: I guess I think of the land as a sort of silent witness. And so then if I pull up some things, then maybe I’m the mouthpiece, or I’m the advocate.

HV: Totally. And silent witness, there’s a big tradition in America, especially of trees being silent witnesses of different kinds of silent witnessing.

AM: Yes.

HV: And one of the things, I think about landscape, I’d love to hear your sort of thoughts about it, but I feel like it also ties into this false idea of the landscape being pristine before Europeans arrived, right? As opposed to Natives who were actually crafting the landscape. And the landscape itself has its own sort of history and power in narrative quality that we often don’t want to see. And I’m curious, does that resonate for you? How do you approach the landscape in different ways?

AM: Again, I get feelings about landscapes, and I think that because indigenous culture is relational with the Native place names, they’re descriptive. But there’s some sort of love that I read in those descriptions. This is the place where the two waters meet, or there’s like a mini poem in these. And so there’s a reverence there and there’s a knowledge there, like “The Knowledge Keepers”. And so I try to be in dialogue with spaces like that.

HV: Yeah. Now we’ve been having this great conversation. Is there anything that we haven’t talked about? And specifically about the Boston work that you’d want to address, is there something about that? Maybe even talk a little bit about how your relationship to a museum like the MFA has changed over the decades.

AM: Yeah. Well, of course, the first time there was interest on their part was in the Hannah Deguia’s photo series that I did. And so they acquired that a few years ago. Fortunately, they have an Indigenous curator there, Marina Tyquiengco. And that’s happening more and more at major art institutions. So it’s nice when museums are opening themselves up to work like mine. And like you say, it’s being integrated now. It’s not like this, “Oh, this is here. This is exotic” ––

HV: This is “Native room.”

AM: Yeah, it’s not like that. But there are still many group shows that are being made where Native artists are not thought of, but it’s changing. It’s starting to change. And that’s really good. I hope that the non-Native curators will continue to learn about our cultures and our artists, because I think that it’s important for curators to be responding to work very honestly and applying the same sorts of critical faculties that they would apply to any work. And I don’t always see that with some of the selections. They seem lazy and not in depth enough. There’s better work by some of these artists or by different artists that they’re not even thinking of.

HV: The last thing I want to ask you about is Robert Smithson, because you have an interesting relationship.

AM: Bob?

HV: Yeah.

AM: Yeah. Well, I’m drawn to the land, and of course I was drawn to artists who are also drawn to the land, but there’s something … it shows hubris.

HV: Yes. What? You don’t think you can just change the landscape whenever you want? [Laughs]

AM: Well, exactly. Okay, so that’s it. So the sense of entitlement that created the United States seems to have empowered these artists who usually aren’t associated with empire or stuff like that.

HV: Yeah. That’s right.

AM: But in a way, they disregarded it.

HV: Well, I mean, isn’t that the ultimate privilege? To be able to ignore it? [Laughs]

AM: Yes. Yes. I mean, in a way it’s extractive, but… I know he’s an intriguing artist for me because he was sort of Icarus. He died in the plane that was looking at one of his aerial views, trying to research a site. So there’s something sort of legendary about him, and also something disturbing… Like this brilliant guy from this little tract house in New Jersey trying to find his way. And in a way, I do love some of his work. I love Spiral Jetty. It’s complicated ––

HV: It is. Well, that’s what I like. I think that’s the sculpture in Boston where you can acknowledge the problem there, but you also want to be in conversation with it.

AM: Yes.

HV: Right? It doesn’t feel like a lecture. And I think that’s why your work works so well. It’s like there’s a conversational quality that brings the viewer in.

AM: Yeah. I believe strongly, and I should tell my students, there has to be some attractor, there has to be some sort of magnet for people to give your work the time of day. Because visual art is the most democratic of arts, I think, because you can get a lot from looking at something in a very short time.

HV: That’s right.

AM: So it’s very economical in a way.

HV: And cross-cultural and all those things that language is not.

AM: Yes. And it has this very compact power that can then have large reverberations. And unlike performance-oriented, even musical or theater or performance art, you’re not stuck.

HV: No.

AM: If it’s not to your taste, you’re not stuck. I love that about a sculpture, something that’s just mute, it’s on the wall or whatever. It’s like, “Yeah, okay.” Yeah.

HV: Totally.

AM: But it’s like ––

HV: And you can consume so much of it in a way you can’t with books.

AM: Yes. Yes.

HV: You can’t with ––

AM: Exactly.

HV: You just take it all in and sift it.

AM: It’s promiscuous, isn’t it?

HV: It really is.

AM: Like, you watch your museum, and it’s like ––

HV: Totally.

AM: “Wow. I’m just too much.” I was just recently in Rome, and it definitely had that.

HV: No, it’s like drinking it in.

AM: Yeah.

HV: It’s like that level, like a fire hose.

AM: Yes.

HV: It’s like drinking from a fire hose a little bit, where it’s all these levels.

AM: Yes. You get that rapture sort of at a certain point.

HV: Yeah.

AM: Yeah, it’s amazing. And it’s intense, and I think that intensity is part of what draws people to art, and it’s often lodged in the artists.

HV: Absolutely. I love that. So my final question is going to be, what is the question you hope people think about when they see your work? Is there a question that you would like them to think about? And obviously there are probably many questions, but I’m just wondering if you could isolate one question that you think really sort of gets at some of the ideas you talk about, and perhaps people sometimes don’t see or discuss as much as they should.

AM: How much is it?

HV: [Laughs] That’s funny, Alan. I like that.

AM: No, no, I ––

HV: [Laughs] Will it fit all my credit card?

AM: I don’t think I’ve ever been asked that, by the way. [Laughs]

HV: Really? [Laughs]

AM: No, it’s clearly a fantasy.

HV: Next time I see you, I’m going to be like, how much is that, Ala? [Laughs]

AM: These things come via email. You just open up one day and it’s like, “Alan, is this available?” And you start to levitate in the chair.

HV: Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

AM: Yeah, so let’s see. A question that I would want people to ask…

HV: Yeah, maybe a conceptual question? Or perhaps, something like, “What is my relationship to this object?”

AM: Yeah. Well, I intend my work to be relational. It’s a set of propositions.

HV: Right.

AM: And so I want people to, if they become engaged with it, to just go with whatever they want to do.

HV: Great.

AM: Yeah. That’s all.

HV: Love that. Well, thank you, Alan. It’s been a pleasure.

AM: It’s been a pleasure.

HV: And hopefully people will see “The Knowledge Keepers,” which will also be part of the Boston Art Triennial.

AM: Right. Which opens on May 22nd to the public. And I believe that “The Knowledge Keepers” is going to be up for longer than a year. I just heard that that might happen.

HV: Whoo-hoo! I hope they acquire it.

AM: Yeah, it was mid-November and now it’s going to be, I think, more than next November.

HV: Right.

AM: And yes, it would be great if they did and write cards and letters.

HV: Right, exactly. Everybody send their energy into the universe. But also just being part of the Boston Art Triennial sounds really exciting too, because it’s going to bring a lot of new eyeballs and context for the work.

AM: Yes. And some really good contemporary Native artists, Nicholas Galanin and the New Red Order.

HV: Oh, yeah. Amazing.

AM: Yes. So it’ll be great.

HV: That’s great. So congratulations.

AM: Thanks.

HV: And hopefully people will spend their time with it and explore all your work.

AM: Ah, thanks.

HV: Thanks so much for listening. This episode was edited and produced by Isabella Segalovich. And like all episodes of the Hyperallergic Podcast, it’s supported by Hyperallergic members. So if you want to join thousands of other people to support the best independent arts journalism out there, telling stories no one else is telling, please consider becoming a member for only $8 a month or $80 a year, because Hyperallergic needs your support to ensure that we can continue to bring the stories you want to hear. Thanks so much for listening to this episode. My name is Hrag Vartanian, Editor-in-Chief and Co-founder of Hyperallergic. See you next time.

[Audio from Alan Michelson, “RoundDance” (2013)]