Apocalypse Art Has Never Been More Relevant

PARIS — Amid collective failures to stop genocide and fascism in 2025, the Book of Revelation’s scenes of vivid combat between good and evil hit home. How satisfying to behold Saint Michael impaling a dragon in a Rhineland manuscript, for instance. At the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) in Paris, a show tracing the Apocalypse across the longer arc of art history is not just another exhibition about the Bible, but a far more biting critique.

Apocalypse: Today and Tomorrow takes place in the exhibition hall of the François-Mitterrand site of the BnF, which holds one of the largest collections of Medieval European manuscripts in the world, having inherited the French crown’s collection after the 1789 revolution. Playing to its strengths, the exhibition displays numerous Medieval manuscripts illustrating the Apocalypse alongside the work of artists who have reinterpreted these themes, including Albrecht Dürer’s woodcuts, William Blake’s lush paintings, and lesser-known engagements by Odilon Redon and Wassily Kandinsky.

The Book of Revelation, previously called the Apocalypse, is the Bible’s most ekphrastic text. With vivid allegorical imagery, its author, John of Patmos, sought to cajole readers into choosing virtue over vice before it was too late. The popular fixation on the end of the world glosses over this ethical imperative: John of Patmos’s overriding concern was moral complacency in the here and now. The fear that this year might be our last was meant to motivate better choices today. John of Patmos wanted readers to vanquish their inner demons and reject the deceptive force of evil. And for centuries, artists have had a field day reinterpreting the jarring visions he offered as motivation.

In Revelation 12, for one, John of Patmos envisions an epic battle between a dragon and a woman clothed with the sun, depicted in a 13th-century manuscript from Salisbury on display in Apocalypse: Today and Tomorrow in impeccable condition. Two centuries later, in 1498, Albrecht Dürer would illustrate this scene in his iconic series of 15 woodcuts, also on view in the exhibition. In both the Salisbury manuscript and Dürer’s woodcut, the woman’s face demonstrates her steely serenity — she is prepared for the inevitable combat with evil.

Elsewhere, Odilon Redon reinterprets Revelation 20, in which an angel locks the evil dragon into an abyss for a thousand years. In his series of 13 lithographs from 1899, Redon leaves the angels out, focusing on evil in the form of an enchained serpent. The grayscale palette imbues the scene with a palpable sense of darkness, alluding to the abyss in a way that the brighter colors of the illuminated manuscript tradition cannot.

The Whore of Babylon in Revelation 17 is perhaps John of Patmos’s most notorious character. It may be tempting to lambast her as the misogynistic result of early Christian slut-shaming. But many scholars believe that John of Patmos was in fact playing with a lesser-known metaphorical tradition in Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Hosea, in which prophets called out men for “spiritual whoring,” or betraying the Shema’s command to love god and instead lusting after worldly power, wealth, and status.

In a Flemish manuscript from around the year 1400 on view at the BnF, the Whore of Babylon is bedazzled in a decadent gown and gold tiara to symbolize that wealth after which many men mistakenly lust. William Blake couldn’t resist making her topless in his 1809 watercolor, which betrays a misplaced erotic charge. The original intention was likely to personify the lust for worldly power as unfaithful to God. Glib as it may sound, when money and power are aggrandized instead of reviled by many purported Christians today, it’s convenient that the original meaning of the Whore of Babylon has been lost in translation.

In Revelation 18, John of Patmos envisions a fire destroying the city of Babylon, followed by a vision of a new heavenly Jerusalem in Revelation 21. The city of Babylon was understood to be an allegory for a city of greed, whereas Jerusalem is a virtuous city of holiness. In an illustration from a 13th-century Beatus Commentary on the Apocalypse produced in Arroyo, Spain, an unknown illuminator vividly depicts Babylon on fire, with people fleeing the building as their worldly possessions are consumed by the flames. The vision of the heavenly Jerusalem is represented by a more abstract, 13th-century edition of Lambert of Saint-Omer’s Book of Flowers, produced in the Cambrai region of France.

Finally, in the Last Judgment in Revelation 20, God metes out punishment to the wicked and rewards the virtuous. The BnF offers a rare opportunity to see its depiction in the 12th-century Psalter of Westminster, produced in Medieval London. Centuries later, Wassily Kandinsky portrayed the Last Judgement in his characteristically abstract painting “Jüngster Tag” (1912), in which two amorphous entities appear to separate, alluding to good on one side and evil on the other.

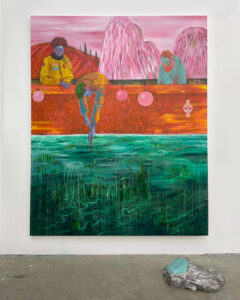

The thesis of Apocalypse: Today and Tomorrow breaks down when we reach the 20th-century rooms toward the end. Most modern and contemporary artists were not interested in the Book of Revelation. At times, it felt like the curators were shoehorning canonical artists like Otto Dix — who exposed the destructive impulses of war and modern society — into the show. A specific focus on artists such as Germaine Richier, whose multi-headed horse in “Le Cheval à six têtes, grand” (1954–56) does work with Revelation as a source text, would have landed better.

Although the final room of contemporary art explores disasters in general, it felt disconnected from the earlier Biblical emphasis. For example, Anne Imhof’s “Untitled” (2022) is vaguely Apocalyptic with glowing plumes of smoke, but it doesn’t engage as directly with the source text. The exhibition strains to include contemporary French and European blue-chip artists, even if they were not directly referring to the Book of Revelation. In many ways, the last room repeats the stretched approach of the Royal Academy’s 2000 show Apocalypse: Beauty and Horror in Contemporary Art, in which any artist exploring disaster was curated as connected to John of Patmos’s text.

Apocalypse: Today and Tomorrow would have benefited from a more narrow focus on the Book of Revelation in the 20th and 21st century, instead of casting a wider net on portrayals of disaster. But it still offers an incredible opportunity to reflect on the choice between good and evil at the heart of the Apocalypse of John of Patmos, and to observe rarely seen manuscripts from the BnF vault.

Right: Detail of unrecorded illuminator’s the Woman and the Dragon, Apocalypse Manuscript (c. 1250), produced in England, probably Salisbury, held in the BnF’s département des Manuscrits Français #403, folio 19 verso

Right: Detail of an unrecorded illuminator’s the Heavenly Jerusalem, in Lamber of Saint-Omer, Book of Flowers (c. 3rd quarter of the 13th century), produced in the Cambrai region of France, held in the BnF’s département des Manuscrits Latin #8865, Folio 42 verso

Apocalypse: Yesterday and Tomorrow continues at the Bibliothèque nationale de France through June 8. The exhibition was curated by Jeanne Brun.