Asian Diasporic Artists Ask How We Create Our Self-Images

PASADENA — One fascinating thing about parenting is seeing how your children combine your mannerisms with their exposure to the larger community in their own developing personalities. My five-year-old daughter loves mimicking the dance choreography of Blackpink and is growing up in a time when K-pop is a global sensation. My preteen daughter loves to read, and her personal library is filled with books by Asian-American authors telling stories that center Asian-American girls. Both girls are growing up in a city with the largest Korean diaspora outside of Korea. I often wonder how simply being exposed to this abundance of Asian bodies and cultural representation — an experience quite different from my own childhood — is influencing their growing senses of self, specifically their racial identities as mixed ethnicity Asian Americans.

my hands are monsters who believe in magic, curated by Kris Kuramitsu at the Armory Center for the Arts, features the work of 10 artists from the Asian diaspora. The exhibition focuses on the fragmented nature of identity and the circular loop of external and internal feedback involved in self-image creation, with particularly interest in how technology and media feeds into this process.

This idea is modeled in Miraj Patel’s installation “Indexing” (2025). Here, a smartphone flashlight shines light through a portrait of the artist onto a British photographer’s colonial-period image of an Indian man, resulting in a hybrid in which the artist’s image is projected onto the colonizer’s abstracting gaze.

Amia Yokoyama’s installation “Wyrm Theory” (2025) similarly reflects this process: fragmented videos of body parts and stop-motion-animated clay forms projected onto a web of porcelain discs and steel wire speak to how the boundaries between the self, the outside world, and the media we consume can become blurred. This makes it difficult to ascertain the difference between personal preference and the internalization of others’ narratives. The narrator in Diane Severin Nguyen’s video “If Revolution is a Sickness,” which loosely tells the story of a Vietnamese girl in Poland joining a K-pop-inspired dance group, sums this tension up succinctly by asking: “Once I memorize their words, will I lose my voice? Is it true that only a photograph can see inside?” Later in the film she declares: “I must appear to myself as I wish to appear to others.”

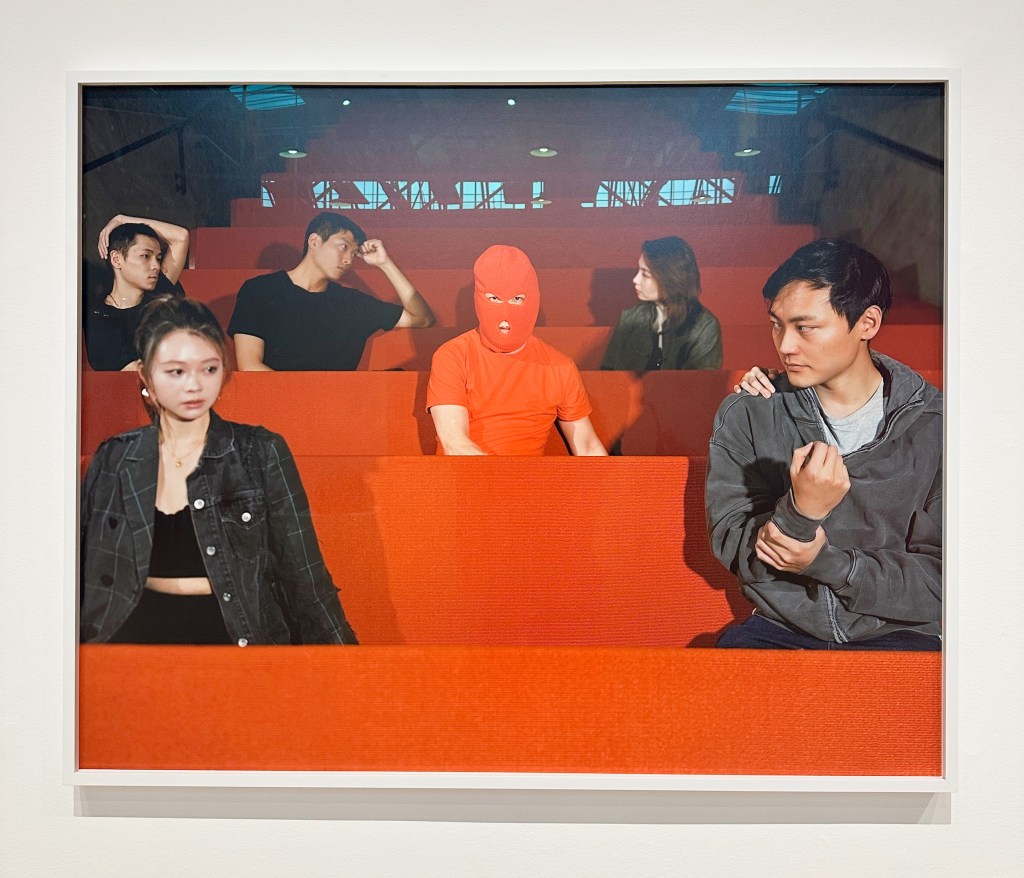

In Jarod Lew’s photograph “Blending in Orange” (2024), a presumably Asian figure wearing an orange shirt sits in a row of orange benches. In order to blend in with the seating, the person has obscured their face with an orange balaclava, which anonymizes and generalizes them. Notably, the other figures in the scene (also presumably Asian) are all dressed in shades of black and gray, without their faces obscured. It’s as if the artist is saying that assimilation into one group necessarily requires both dissimilating from another group and a disintegration of self. The figure in orange stares back at us, asserting their agency in this performance of both assimilation and self-obliteration.

Perhaps in the end the only authentic Asian-American identity is personal and individualized. In other words, we can only truly blend in with our selves. The paradox is that this individual authenticity can only be envisioned and visible in the context of and in response to others — our family and our communities, and through the representations and narratives we consume.

my hands are monsters who believe in magic continues at the Armory Center for the Arts (145 North Raymond Avenue, Pasadena, California) through December 14. The exhibition was curated by Kris Kuramitsu.