Blue-Chip Works by Rothko, Richter, and Picasso Headline Art Basel, Where Dealers Cast Wide Range of Price Points and Styles Against Market Uncertainty

For decades, Art Basel in Switzerland was the only fair that mattered—the undisputed apex of the art market calendar. But in 2025, that certainty has splintered. With a bloated and chaotic global fair circuit and new contenders arriving every year (oh, hello Art Basel Qatar), even loyalists have started to ask: is Basel still top dog? For the galleries that brought the right material, it would seem so. David Zwirner sold a sculpture by Ruth Asawa for $9.5 million and a Gerhard Richter painting for $6.8 million. Gladstone sold an untitled Keith Haring from 1983 for $3.5 million, while White Cube moved a Georg Baselitz for €2.2 million. Thaddaeus Ropac also did especially well, with a Baselitz going for over $1 million.

This year, Art Basel, now in its 55th edition, opened under clear skies and heat—80 degrees Fahrenheit and climbing. For the 291 exhibitors participating, it’s the last chance to reframe a summer season defined by tepid auctions and cautious collecting.

In a soft, unpredictable market, the smart dealers have realized that the most effective strategy is to hedge their bets by casting a wide range of price points, periods of art history, and artistic styles. As art adviser Gabriela Palmieri put it, “Uncertainty in the world is mirrored by the uncertainty over what will motivate even the most discerning collectors. The response has turned Art Basel into a place where more really is more.”

Galleries that have previously relied on previews and multiple reserves (they still do) are now betting on volume and visibility as well. Robert Diamant, the founder of Carl Freedman Gallery in Kent, England, which isn’t showing at the fair this year, told ARTnews on the sidelines that collectors are increasingly snubbing more “academic works” rooted in art history in favor of “colorful things.”

Moody Rothko Steals the Show

Talk of the conflicts raging in Ukraine, Gaza, Israel, and Iran is hot on fair-goers’ lips, but that hasn’t deterred wealthy collectors from lounging in the fair’s sunbaked courtyard while sipping champagne and slurping back oysters. Art Basel is a bubble.

Was the heat making buyers lethargic? David Nolan, founder of his eponymous New York gallery, thought so. “It was a little slower than usual, however, business remains healthy overall,” he told ARTnews. “We’ve made some sales to new clients, though the majority have been to clients known to us.”

Hauser & Wirth, Switzerland being their home turf, naturally came out with force by headlining its booth with a hypnotic, moody Mark Rothko from the early 1960s. The painting wasn’t on any of the PDFs circulated by the gallery ahead of the fair. “There’s only so much you can see on a screen—nothing replaces the moment you stand in front of a work in real life,” Iwan Wirth, the gallery’s cofounder, told ARTnews.

The work, No. 6/Sienna, Orange on Wine (1962), was first shown in the1964 exhibition that introduced Abstract Expressionism to Switzerland, “Bilanz Internationale Malerei seit 1950” at the Kunsthalle Basel, just on the other side of the Rhine from the Messeplatz. While the gallery wouldn’t share the price, works from this same year have sold for between $30 million and $50 million at auction in the last 20 years, including at Christie’s in 2022.

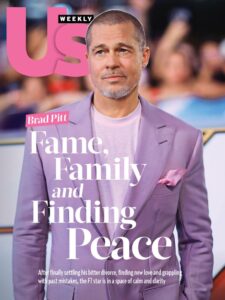

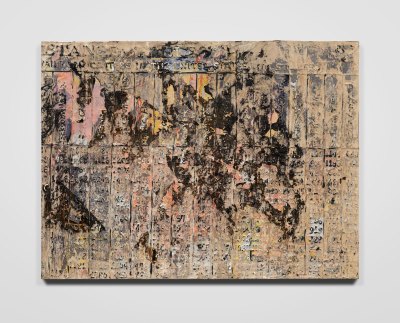

Mark Bradford, Ain’t Got Time To Worry, 2025.

Photo Keith Lubow/© Mark Bradford/Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

When asked if Basel’s Art Basel still has the sway it once did, Wirth gave a confident “yes,” adding that “a lot of people start collecting here because it’s a great introduction to the art world. It always has been.”

Many of the gallery’s mid-career stars—such as Rashid Johnson and Mark Bradford—are presenting new work that looks backward, toward early influences, modernist touchstones, and overlooked figures in art history. One of Johnson’s new “Quiet Paintings” revisits the material-heavy techniques of his earlier career—scraping and layering into thick surfaces, while tilting its hat to influences from art brut and Sigmar Polke. Titled Spectrum (2025), it sold for $1 million on Tuesday. The gallery also sold two works by Bradford for $3.5 million each, two George Condo’s for $2.45 million each, and a Louise Bourgeois for $1.9 million.

An untitled painting, from 1957–58, by Joan Mitchell in Pace’s booth at Art Basel 2025.

©Joan Mitchell Foundation/Courtesy Art Basel

Hedging Bets, Alleviating Risk

Pace’s booth at Art Basel is organized with a deliberate split: fresh contemporary works are shown along the outer walls, while the gallery’s historical masterworks anchor the interior. The presentation spans a wide price range—from under $30,000 to a $30 million Picasso—making clear that the gallery is covering all corners of the market.

Among the contemporary highlights are Pam Evelyn’s Focal Length (2025), which sold for $85,000, and Kylie Manning’s Jetty (2025), bought for $115,000. Inside the booth, near $30 million Picasso is a major Joan Mitchell, both works on reserve at the close of Art Basel’s first preview day.

Pace reported over strong first-day results, including Agnes Martin’s Untitled #5 (2002), which sold for over $4 million, and Emily Kam Kngwarray’s Anooralya – Yam Story (1994), which went for $450,000. Other key sales included Arlene Shechet’s Fictional First Person (2025), snapped up for $150,000 and Elmgreen & Dragset’s The Visitor (2025), sold to Leipzig’s G2 Kunsthalle for $300,000.

Pace’s least pricey offering was Li Hei Di’s artwork Triple Flood (2025), which sold for $28,000. Over at Marianne Boesky’s booth, prices started at a similar point. Boesky told ARTnews that she is “insulating” her booth from the “challenges impacting the secondary market” by offering “primary market material at attractive price points between $30,000 and $1.8 million.”

Gagosian’s booth at Art Basel 2025, featuring Pablo Picasso’s Tête de femme (1951) and Enfant assis (1939).

Photo Owen Conway/© 2025 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy Gagosian

Gagosian, too, is casting a wide price net with a selection of works roughly between $30,000 and $2 million. Its booth, curated by the Venice Biennale and MCA Chicago veteran Francesco Bonami, straddles secondary market gems and new works by Jadé Fadojutimi, John Currin, and Sarah Sze. These are hung next to notable pieces by Christo, Picasso, and a grisly Richard Avedon image of Andy Warhol’s mangled torso.

It would be absurd not to mention that the entrance to Gagosian’s booth has a retooled version of Maurizio Cattelan’s infamous Him (originally a kneeling Hitler effigy). For the reworked version, dated 2021, titled No, Cattelan has covered the dictator’s face with a paper bag, keeping his piously interlaced digits and infamous herringbone suit.

Gagosian’s booth at Art Basel 2025, featuring Maurizio Cattelan’s No (2021), foreground, and a 2023 untitled painting by Rudolf Stingel.

Photo Owen Conway/Courtesy Gagosian; Art, front to back: ©Maurizio Cattelan; ©Rudolf Stingel

Brisk Sales and ‘Less Americans’

Thaddaeus Ropac reported brisk sales by early afternoon including James Rosenquist’s Playmate (1966), which sold for $1.8 million to a European institution; 1981’s Lipstick (Spread) by Robert Rauschenberg for $1.5 million; and Claire McCardell 9 (2022) by Alex Katz for $800,000. The gallery also sold three works by Baselitz including Hier jetzt hell, dort dunkel dunkel (2012) for $1.8 million. (Baselitz, along with Lucio Fontana, will be the first two artists shown at Ropac’s new Milan gallery when it opens in September.)

David Zwirner had sold 68 works from its stand by 5 p.m. The most notable the $9.5 million Asawa and $6.8 million Richter, as well as two new works by Dana Schutz, which sold for $1.2 million and $850,000. Zwirner also has on offer a Richter that, according to a well-informed adviser, is priced at $28 million. (A Zwirner rep said the gallery is not disclosing the price of that artwork.)

Over at White Cube’s booth, shortly after the first groups of collectors had entered the Messe, a stern Jay Jopling, the gallery’s founder, told ARTnews it was “a bit early to reveal any prices, but we’ve already sold loads of stuff.” They included David Hammons’s Untitled (2012) and Red Birds (2022) by Cai Guo-Qiang. Jopling declined to disclose prices.

The gallery’s global sales director, Daniela Gareh, later told ARTnews that “it’s been a strong first day—we’re particularly pleased with the institutional placement of several key works.” They include three editions of Danh Vo’s In God We Trust (2025) that went for $250,000 each. Two were sold before the fair kicked off and another on Tuesday. Guo-Qiang’s Red Birds went to an unnamed European institution for $1.2 million.

Mathieu Paris, the gallery’s senior director, told ARTnews that “there are definitely less Americans at the fair this year.”

White Cube also sold a Baselitz portrait of the artist’s wife made in 2023 for $2.2 million, a large-scale work by Tracey Emin for over $1 million, and an acrylic on canvas painting by the late Sam Gilliam for $975,000.

View of White Cube’s booth at Art Basel 2025.

Photo Alex Burdiak/Courtesy White Cube

‘Great Atmosphere’

Art Basel’s CEO Noah Horowitz said this year’s edition felt more focused—less party chatter, more serious engagement with the art itself. He pointed to a broader generational and geographic mix on the fair floor, and noted that for younger collectors, Basel remains “a rite of passage” regardless of what anyone says. Basel’s bid to stay culturally relevant while navigating a market in flux can be seen clearly in the Unlimited sector. Once dominated by older European men, now reflects a wider range of perspectives, Horowitz said, from American artists like Diane Arbus, Lorna Simpson, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres to artists from Lebanon, Greece, and Russia.

Andreas Gegner, a senior director at Sprüth Magers, told ARTnews that “we are having a fantastic first day at the fair—the atmosphere is great.” The gallery’s sales included Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (WAR TIME, WAR CRIME), from 2025, for $650,000; HORIZON. Shortness of Breath (2025) by Sterling Ruby for $350,000; and Rosemarie Trockel’s Golden Brown (2005) for $850,000.

Not all works were flying off the shelves, though. It was tougher going for Mazzoleni Gallery, with spaces in London and Turin, which was struggling to find a buyer for a shredded Lucio Fontana made out of copper titled Concetto spaziale (1962). In fact, the gallery, which is displaying a selection of Italian masters, was still waiting to confirm a deal, but said there had been “lots of interest.”

Ashkan Baghestani, Sotheby’s vice president and head of sale, told ARTnews that “if you look around the fair, there’s obviously still a lot of wealth in the world, despite what’s going on.”

He continued, “The May sales were really positive for us, all the small collections we had did well, anything under $2 million did super well. There was depth of bidding, records for artists, quality of property, so I think this brings positivity going into Art Basel.” He added that he’s looking forward to seeing how Art Basel’s new fair in Doha plays out in February. “I’m excited. It’s smaller, very well curated, it will be interesting.”

Olga de Amaral, Lienzos C y D, 2015.

©Olga de Amaral/Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Louise Hayward, a London-based partner at Lisson Gallery, told ARTnews that Art Basel “still represents the climax of the year for us.” By midday, the gallery’s confirmed sales included Dalton Paula’s Xica Manicongo (2025) for $200,000, Lee Ufan’s Response (2025) for $850,000, and Olga de Amaral’s Lienzos C y D (2015) for an undisclosed sum.

ARTnews asked a despondent Kenny Schachter, the artist and Artnet News columnist, if he thought the fair had lost any gravitas over the last few years. “I measure my life by how many Art Basels I have left, so if I go by the ‘Gagosian scale,’ I’d say I have about 17 remaining, and it’s not getting any better—it needs more vitality,” he said, noting that Basel Social Club, a startup fair a 20-minute walk from the Messeplatz, had “invigorated me. You want to see new ways of thinking. The art world is the most staunchly conservative industry, nothing prepared me for how backward-looking it is. It’s so resistant to change, and that’s disappointing.”

So, did Basel’s first VIP day mark a rebound, a reprieve, or a launch of a new maximalist strategy? Depends on who you ask—and how much they sold.