Chaos and Control: The Rise and Fall (and Rise Again) of Liam and Noel Gallagher

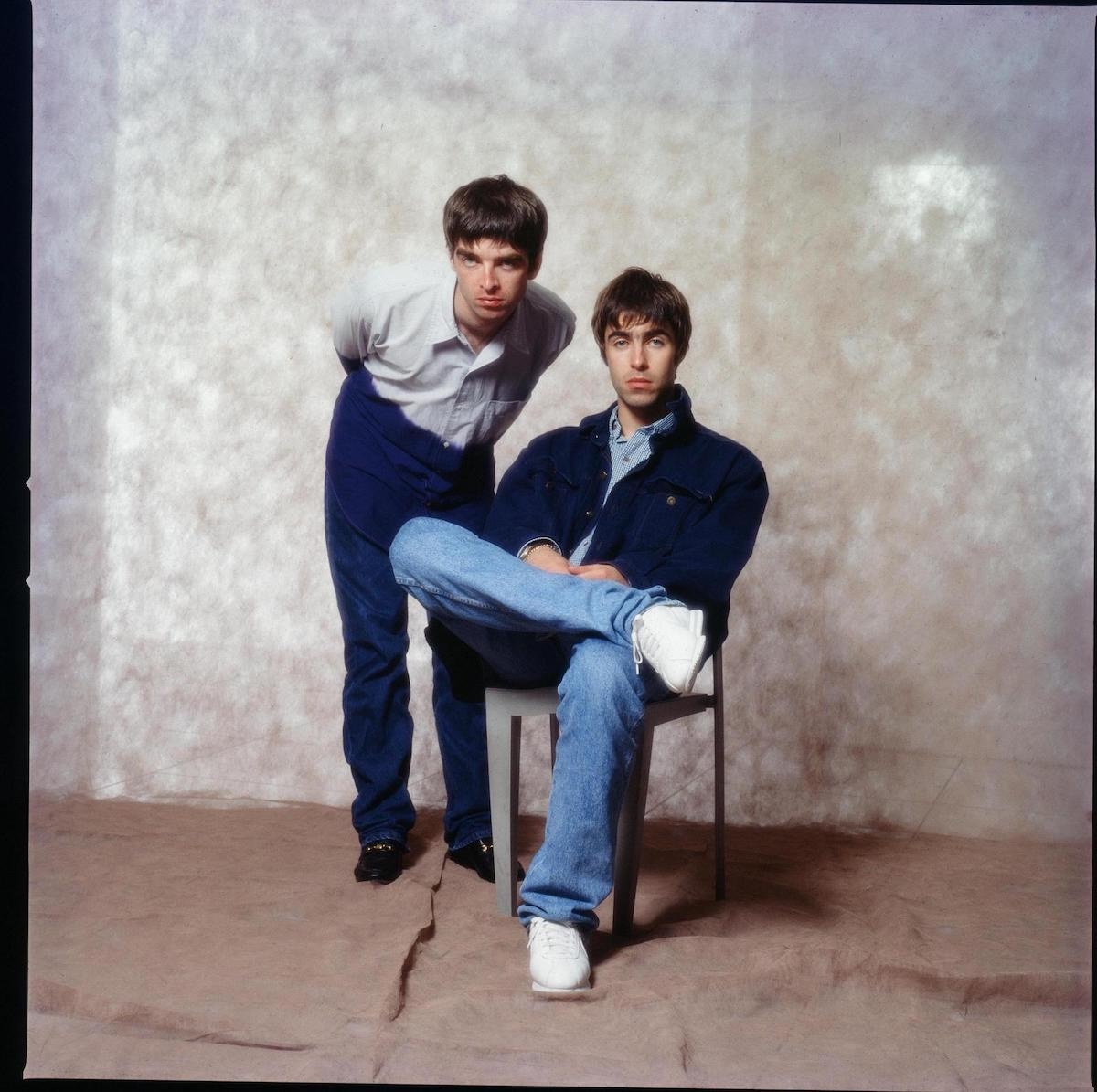

Oasis never did anything quietly. Not during the band’s first 15 years together, leading a ’90s Britpop movement with distorted guitars and soaring melodies, and certainly not with last year’s surprise announcement of a global reunion tour in 2025. At the center of that story are brothers Noel and Liam Gallagher, a couple of Manchester, England, bad boys who did very, very good.

The tour will reunite the oft-warring siblings for the first time since their acrimonious, and probably inevitable, breakup in 2009. For long-suffering fans, and a new wave of curious younger followers who never got a chance to see Oasis in action, the tour will bring new life to a career that began with the sensation of their 1994 debut album Definitely Maybe and 1995’s (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? Dates begin this July in the U.K. and Ireland, followed by North and South America, Asia, and Australia. (Tickets for the North American tour sold out in an hour.)

More from Spin:

- Tropical Fuck Storm Batten Down the Hatches

- A Decade of Feeling ‘Emotion’: Looking Back at Carly Rae Jepsen’s Most Underrated Album

- Young Thug Welcomes Travis Scott, T.I. At First Post-Jail Show

With the first concert in Wales now less than a month away, Oasis are currently deep into rehearsals, where the band is sounding “fucking FILTHY,” as singer Liam posted enthusiastically on X.

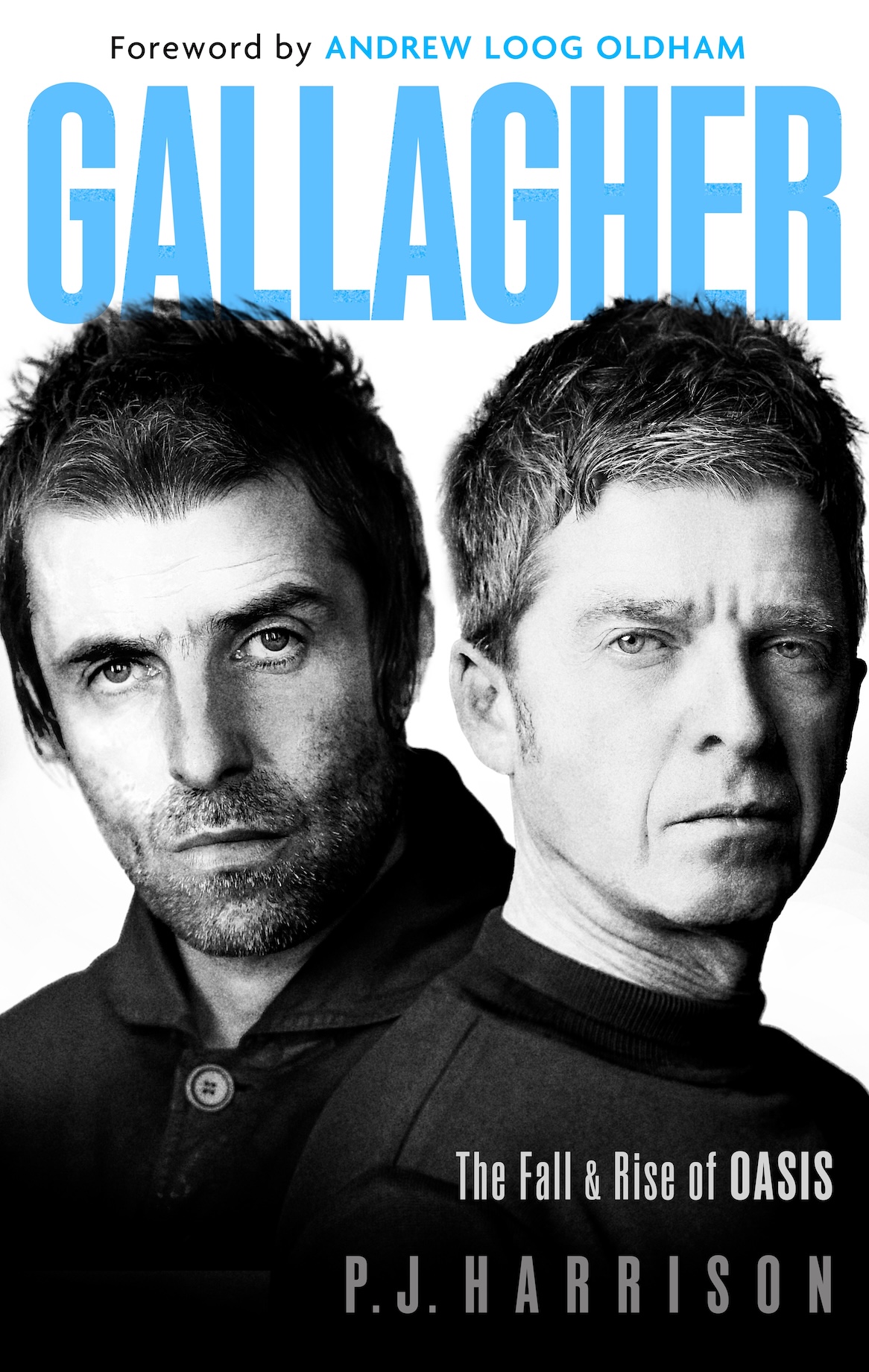

Among those paying close attention is P.J. Harrison, a former label owner and artist manager, who has written a new book, Gallagher: The Fall and Rise of Oasis. Starting as an adolescent fan of the first Oasis releases, Harrison later became a sometime associate and observer of the band on the road and, for one day, in the studio.

The book, released this August, is less a traditional band history than a deep look at the family dynamics within. Noel, the oldest by four years, was the musical mastermind and songwriter behind the guitar, Liam the sneering rock star at the mic. They represented a Britpop movement that also included Blur, Supergrass, and Pulp. While loud guitars had already made a comeback through the grunge explosion in the U.S., Oasis touched a nerve by melding classic rock with post-punk attitude and mod haircuts. The early records mined T-Rex on “Cigarettes & Alcohol,” Rolling Stones swagger on “Supersonic,” and large-scale Beatles psychedelia on “Champagne Supernova.”

Harrison was among that first generation of followers, so he’s spent a lot of time thinking about the Gallaghers, once known as much for fights in hotel bars and alarming press interviews as radio hits. In the book, he closely examines their upbringing and their later solo careers, and describes the lingering impact on his generation of their rise from working-class Manchester.

“It just came along at that right moment in time when you’re entering your adolescence and there’s this exciting thing and it feels like it’s yours,” says Harrison, who came from a similar background in Liverpool. “It gives you the sense that actually you might not have to work in the factory. You might be able to do something else. And that’s priceless, because it certainly wasn’t coming from the school teachers or from the government. It had to come from somewhere.”

What was your reaction when you heard that Oasis was reuniting for a tour?

I was a little surprised, actually. I mean, not shocked. It always seemed possible, but I started to feel like maybe enough time had gone on that it might not happen. At some point you’re a bit too old, right? I was really impressed at how secret they kept it.

When it was announced, there was a lot of excitement and shows were quickly selling out. Where did the intense demand come from?

I think back to myself as a teenager and discovering the likes of the Rolling Stones way, way after their prime. Obviously, they hadn’t split up, but there’s that generation gap thing that happens where something catches a wave of people coming through and it moves into a space of being a heritage act. [For Oasis] it was probably the perfect amount of time between breaking up, having fans who were around the first time still be young enough to want to go to the shows, plus have these generations of younger fans excited by this big act from, well, history. It’s funny how time can be a bit of a head-fuck. If I think of Is This It by the Strokes now celebrating 24 years, that’s kind of scary. Plus Liam in particular had done a good job of keeping the Oasis experience relevant.

In what way?

If you go to Noel’s shows, you get the songs, and it’s a good time. If you go to Liam’s shows, you get the experience, and you can only get that with him. He’d built a solo career that had stayed on the younger side of the audience, which is very tricky, particularly in the U.K.—but also from his social media usage. He transcended music and he found a great place for his voice—occasionally not the best place for it—in Twitter and other social platforms. And that captured the imagination of a younger crowd. Also, there’s an absence of guitar bands really dominating, so the path’s somewhat cleared for a heritage guitar band to come back in.

Does it make sense to you that Liam would be the one who made this reunion happen?

That’s a characteristic of his. The people who know him very well feel like he’s a person who’s very family oriented. He doesn’t really want to split that unit, and he tends to be the person to reach out. They’re two stubborn people, but I think Noel’s more stubborn. The thing with Liam, he does have to kind of break it before he then pieces it back together. [Laughs].

What led you to write this book?

I was a long-term fan from my adolescence. I was in Marina del Rey [Los Angeles]. I’d been there for a few months and then COVID happened. I’m looking at the marina from my apartment, thinking, “Well, what am I gonna do? I’m gonna go crazy.” The idea started in my mind that Liam is this fascinating person, but in the U.K. the public perception is of this tabloidy 1990s guy who is drinking beer, getting into fights. And that’s a long time ago. That’s a young man who’s gone from being on [public] benefits to being in the world’s biggest rock band in a space of 18 months. It’s a huge trajectory and an invasive level of fame. He is different now. He’s built this extraordinary solo comeback.

He’s worked to reconcile his family and move all of the pieces of his life back together. It’s surprising that there’s no biography about him, telling that story. [The book originally] was a study of the two solo careers. And then it just happened to coincide with them getting back together. That was a happy coincidence. Why is everybody so fascinated by these two brothers? Well, it’s because they don’t really get on, but when they’re together, they have this energy to them. Let’s try and get to the bottom of this if we can.

What is the essential difference between those two?

Noel is somebody who is okay in his own space and has the ability to compartmentalize and cut things off and ostracize people if needed. I think Liam needs that attention from his big brother, and he’s always trying to lean into Noel. I should say also with this I worked with a number of therapists, just to make sure that any behavioral observations were fair. So there’s the idea of the responsible child, which is Noel. He kind of thrives in professionalism and control and order. And Liam thrives in mayhem and chaos and rock and roll in his mind. So that dynamic, since they were children, is who they’ve always been, and it just keeps repeating.

You write a lot about where they’re from. How did that fuel what they became?

When it comes to Manchester, the social conditions were very specific. You have weather that’s similar with Seattle, but whereas the bands [there] that were coming out at the same time expressed downer kind of negative views [musically], the British pop sensibility has always been a bit more positive and upbeat. If things aren’t very good, the last thing you want to do is sing about that. You want to think about something that’s going to lift you up. In terms of class, they’re from a broken family, second generation, immigrants, domestic violence in the home. That’s not an uncommon story in that part of the world. And it’s hard. I don’t think people view them with the correct level of empathy. Classism informs everything in Britain, so it’s easy for people to say, “Oh, look at these louts, these Neanderthals.” And it’s actually, well, no, they didn’t have the same opportunities. They come from a very difficult background, and they were given some pretty appalling examples of how to be, and a lot of trauma thrown in with that.

They come from those backgrounds and succeeded to the level they have. At that point in time, you just didn’t see people like Oasis on TV. If you were my age growing up, in similar circumstances, you didn’t see those people. So these guys who look like ordinary lads, taking on the world on their own terms, who sounded and looked like you, was just huge. It gave a whole generation of people the idea that it was possible for them.

From that perspective, are they in the tradition of previous generations of British rock bands, like the Sex Pistols or the Beatles?

I think the Pistols sonically had a bigger influence on Oasis than the Beatles. Obviously, in terms of inspiration and a muse-like figure, the Beatles are above all for Oasis. But to me, they sound a lot more like the Stones and T-Rex and the Pistols than they do the Beatles. It’s the underclass doing something they shouldn’t really be doing in theory and succeeding. And that’s the thing that’s inspiring. And the same with the Beatles. That entire phenomenon came about from these working-class lads and one middle-class lad from a very tough post-war Liverpool.

What was the impact of those first Oasis albums?

If you think of where music was at in Britain around that time, there was a lot of U.S. R&B on the radio. There was quite a lot of dance music. There weren’t really guitar bands around. Definitely not cool ones. With the first Oasis album and some of the other bands that came around that time, it made the guitar and the rock and roll band seem like the coolest thing ever. And culturally, that was how it was for a decade. It meant that in every music shop in Britain, there were adverts saying, “Guitarist wanted for band, influences: Oasis, the Beatles.” Nirvana in the U.S. had a similar effect. It just changed everything.

They had a pretty entertaining and controversial media presence even outside of whatever songs they had on the radio or on MTV. Claiming to be better than the Beatles got people upset at the time.

They continue to be a gift to the media. They are both quote machines. Liam’s funny in a sort of surrealist kind of way. Noel’s just a witty fella, and they both find it quite hard to resist taking shots at people, including each other. They’ve got that skill of the precision barb. If you put them in a room together in the ’90s, the interview would often turn into an argument between the two of them as well. So that’s kind of incredible for the journalist.

What about their rivalry with Blur? I’m sure that was good for both of them.

I kind of wonder what it may have done to some of the stress levels, but commercially it was probably good for both of them. I think that was just manufactured by Blur’s label and NME, and what they were playing into, again, was the class thing. [Blur] were these art school boys from Essex, which is the antithesis of these council estate yobs from Manchester. They have a twinkle in their eye and all of those more middle-class characteristics versus these guys who are quite direct and don’t mince their words.

How did you first enter the Oasis world and what did you see there?

I used to work with the Redwalls from Chicago. We were great friends and Oasis took them on tour. That was the first introduction, but I had multiple bands that I worked with, so it was a thing that just kept happening over a few years—from about 2005. You’d go on the road for a few months at a time, and just sort of naturally start spending time together [with Oasis]. It was great. I didn’t see any nonsense between the two brothers.

I never spent social time with them both at the same time. You’d either be in Noel’s room or Liam’s room. And then there was a time in the studio at the Village Recorder in Westwood [Los Angeles]. Liam had gone to get married, but I don’t think he told anybody. So he just wasn’t there. [Laughs] Noel was there.

The title of your book is Gallagher, not Oasis. Clearly the most important thing about the book and the reunion is those two together.

When Oasis started out, they were a gang. And I love any band who look like a gang of friends. It’s so romantic. And that was the power. And then as Bonehead [aka Paul Arthurs], Guigsy [Paul McGuigan], and [Tony] McCarroll dropped out of the picture, it became about Noel and Liam, and if you look back on it, it probably always was. So I called it Gallagher because I wanted it to be more of a story about family and trauma and toxic masculinity in a way. I wanted to focus on the story of two men. So it’s an Oasis book, but it’s about the two men called Gallagher.

What do you imagine the incredible public response to their reunion announcement will do for them or to them?

Legacy and ego are important to artists, and there’s a little itch there that wasn’t scratched in the way they bowed out, not quite being on their terms. They obviously cleaned up during the years that they were touring, but the live arena moved on. Probably, when they look at people like Taylor Swift, they think, “God, imagine we were getting that.”

America’s the most interesting part of it, because they’ve done everything in Britain—they’ve played the biggest shows people could do. They couldn’t be bigger. In the U.S., every time it was set up for them to come in and take off, they fell out with each other or something. So it’s time to right that wrong. Doing huge NFL venues in the key [American] cities is something they’ve never achieved before in their career. That’s a new achievement for them.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.