Chloë Bass Eschews the Clichés of Mixed-Race Art

Chloë Bass likes to people watch, and our emotions are her medium.

She’s part of a lineage of artists across fields who critically explore race and social performance, eschewing simplistic narratives — from writer Danzy Senna to the late conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady. Bass’s practice of using text with assemblage, mirrors, and urban signage embodies what she has described as “emotional wayfinding,” the semiotics of our emotional lives and the social and political undercurrents that shape them, on the level of individual neural pathways and latticed networks of families and strangers. Bass requires us to slow down and sit with ourselves, an increasingly difficult task in 2025. What feelings, moods, and memories can words conjure? What emotional traces linger when you take those words away?

These questions bubble up to the surface of Twice Seen, Bass’s solo exhibition at Alexander Gray Associates, dedicated to O’Grady herself. Here, Bass plumbs mixed-race life and the puzzles of visibility, double consciousness, and perception through two works: “we turn to time” (2024), a multi-channel video installation; and “PRETEXTS” (2025), three text-engraved mirrors hung across from descriptions of poetic scenes. As she told Hyperallergic in 2023, her practice is partially rooted in a concerted effort to “emotionally reach people where they’re at.” In Twice Seen, she walks the path alongside us.

If you’ve been on TikTok in the last four years, you’ve seen the “mixed-girl poetry” skits and overzealous “nobody ever thinks I’m Indian” videos. These annoying and, more importantly, self-exoticizing, additive approaches to mixed-race art and political expression sprang to mind as I stepped into Twice Seen. The two works on view refuse to parrot such longstanding myths of mixed-race Black people as “tragic,” or saccharine, often apolitical romanticizations of in-betweenness. Bass’s artistic practice, grounded in her own background as the only child of a Trinidadian artist and poet and a Jewish psychoanalyst and translator, predates and will certainly outlive the tired TikTok clichés.

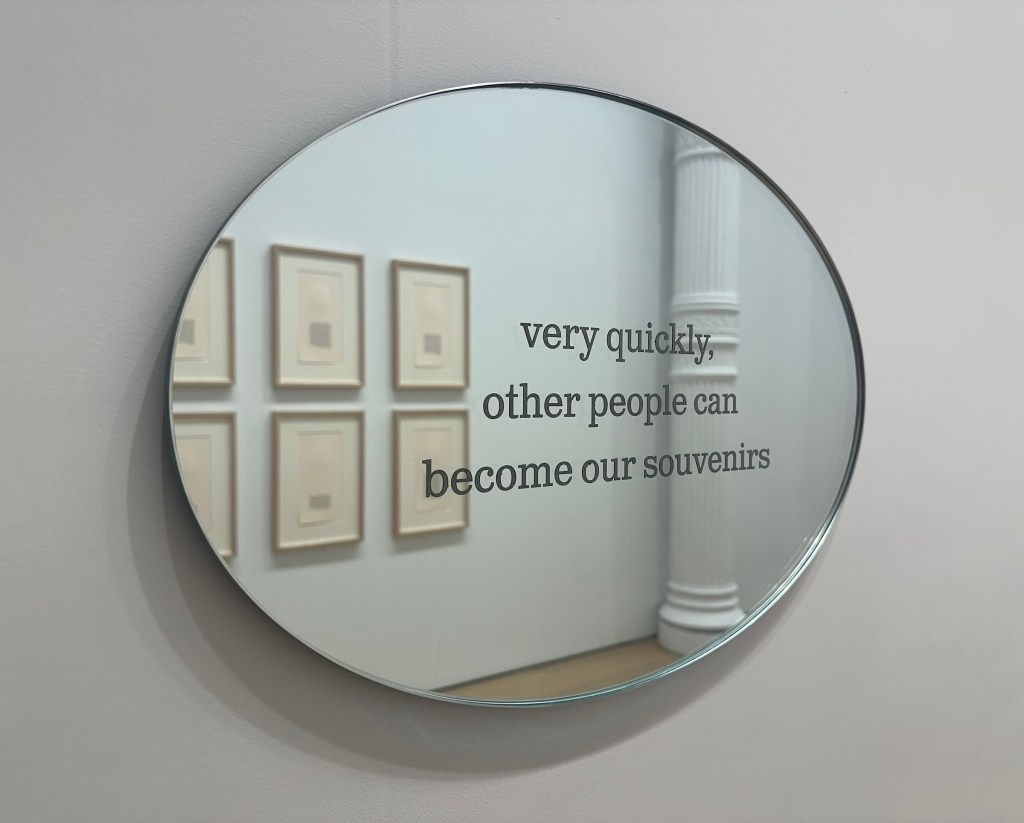

The three engraved oblong mirrors in “PRETEXTS” drew me in immediately with their painful truth: “very quickly, other people can become our souvenirs.” Reading this sentence unleashes a flood of historic and contemporary wounds, evoking the centuries-long practice of turning a person into a thing, dehumanized for enslavement and collection. The following mirror nudges us to the next step: “unremarkable things will happen, made special by their capture.”

Each word has clearly been carefully chosen and inscribed. I couldn’t help but think of recent campaigns for Western museums to repatriate artworks and human remains, and Tamara Lanier’s victory last month in her legal battle with Harvard University to reclaim daguerreotypes of her enslaved ancestors, Papa Renty and his daughter Delia. “Capture,” too, feels like an intentional reference to the same forms of violence and co-optation that Bass is interested in, while implicating photography and visual art in their perpetration — and even us, the viewers, who are caught in the mirror’s frame, if only for a moment or two.

The message on the third mirror points to the future: “the accumulation of tiny moments builds the greatest reverence of all.” On the opposite wall, a set of six sheets Bass salvaged from her mother’s printing process bears letterpress texts, narrating a scene from a film we cannot see: a 1960s home video of family members dancing.

This is not a set of affirmations or feel-good platitudes. I took it as a challenge from the artist. She’s daring us — particularly those of us from multiracial backgrounds — to redefine “capture,” to pay attention to seemingly unremarkable things, and refuse to turn ourselves and one another into novelties.

Nothing in “we turn to time” is particularly remarkable. The video installation, in the next and final room, shows clips of meals and everyday life filmed by American mixed-race families and projected onto four white walls. Parents and children goof around before a meal, cousins put on a performance of “Let It Go” from Frozen, grandparents evaluate the next generation’s cooking skills. Each family’s home movie flickers to life, cuts to black, and crops up on a different wall. It’s a cacophony of tender scenes that we may not expect to encounter in a gallery, but it inevitably ignited my own memories of gatherings, loved ones, shared meals, and play. Crucially, it’s not possible to watch every scene. Some moments will slip through your fingers like sand, but the ones you catch are precious.

Chloë Bass: Twice Seen continues at Alexander Gray Associates (384 Broadway, Tribeca, Manhattan) through July 26. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.