Depicting the Unseen: Yiqi Zhao on Migration, Memory, and the Female Form

Yiqi Zhao is a visual artist and illustrator whose work exists in the potent space between personal myth and social critique. Navigating themes of gender, migration, and cultural identity, Zhao employs a distinct ink-based visual language that draws heavily on surrealism and symbolic subversion. Her meticulous yet emotionally raw compositions interrogate how the body, especially the female form, is shaped by external systems of power and expectation. From intimate watercolours to dense ballpoint pen illustrations, Zhao’s art captures what it means to endure, adapt, and reclaim.

This is most vividly seen in her Limited Strength series, a collection of works that transforms traditional Chinese symbols like cranes, mirrors, and flowing hair, into complex metaphors of restraint and resilience. In Escape, the viewer is met with a striking visual vortex of figures submerged in ink-dark waters, their long hair entangling and anchoring them. One woman rises defiantly above the chaos, pulling herself upward with her own hair—a lifeline as much as a tether. Other works in the series such as Safe House or Jail? And Shut Up intensify this tension, depicting crouched, faceless bodies ensnared by decorative yet oppressive motifs. The technical precision of her lines contrasts with the raw urgency of her themes, creating a sense of internal rupture contained within meticulously drawn forms.

In this interview, we explore how Zhao reclaims the human figure as a site of both struggle and resistance. We discuss her symbolic vocabulary, why hair recurs as both shackle and strength, how the act of concealment becomes an act of commentary, and how her transnational journey from China to the U.S. and now the UK informs her layered, often haunting narratives. What emerges is not just an artist documenting emotional states, but one reshaping visual culture through deeply personal and politically charged storytelling.

In Limited Strength, you reclaim the nude female form through ink and surrealism. How do you balance vulnerability and defiance in these depictions, and what makes the body such a powerful site for resistance in your work?

The nude body, for me, is a battleground where vulnerability and defiance collide. In Limited Strength, I use ballpoint ink—a medium as unyielding as societal scrutiny—to etch figures whose postures oscillate between collapse and rebellion. In Shut Up, a woman’s hair morphs into barbed wire, ensnaring skeletal cranes (traditional symbols of wisdom twisted into oppressors). The body’s power lies in its unapologetic presence: nakedness strips away armor, forcing viewers to confront raw humanity. Defiance isn’t found in grand gestures, but in the quiet act of occupying space without flinching.

Traditional Chinese symbols, like cranes or hair, appear as both lifelines and restraints in your work. How do you intentionally subvert these motifs to critique cultural and patriarchal narratives?

Cultural symbols are palimpsests—we inherit their beauty, but also their burdens. Cranes, emblematic of longevity and nobility in Chinese tradition, become jagged enforcers of silence in Shut Up, pecking at a woman’s throat. Hair, traditionally a marker of femininity, transforms into chains or weapons. By distorting these motifs, I mirror how patriarchal systems weaponize tradition: what was meant to elevate becomes a cage. Subversion here is survival—a way to reclaim narratives buried under centuries of expectation.

Vagabondage captures the emotional cost of migration through a single glowing umbrella. What does this fragile object reveal about your experience of displacement, and how do you translate that into visual language?

The yellow umbrella in Vagabondage is my paradox: a shelter so fragile it threatens to invert into a cage. Its glow is a desperate plea for visibility—See me, but don’t define me. I painted the umbrella suspended in a muted rain, its interior cradling a figure dotted with sparse, starlight-like droplets—subtle brushstrokes hinting at her ambivalent ties to the world. Floating in gray-toned drizzle, the umbrella becomes both cradle and isolate. Displacement is not just physical—it’s a state of psychic suspension, yearning to be acknowledged yet resisting categorization. The umbrella isn’t refuge; it’s a translucent boundary between self and other.

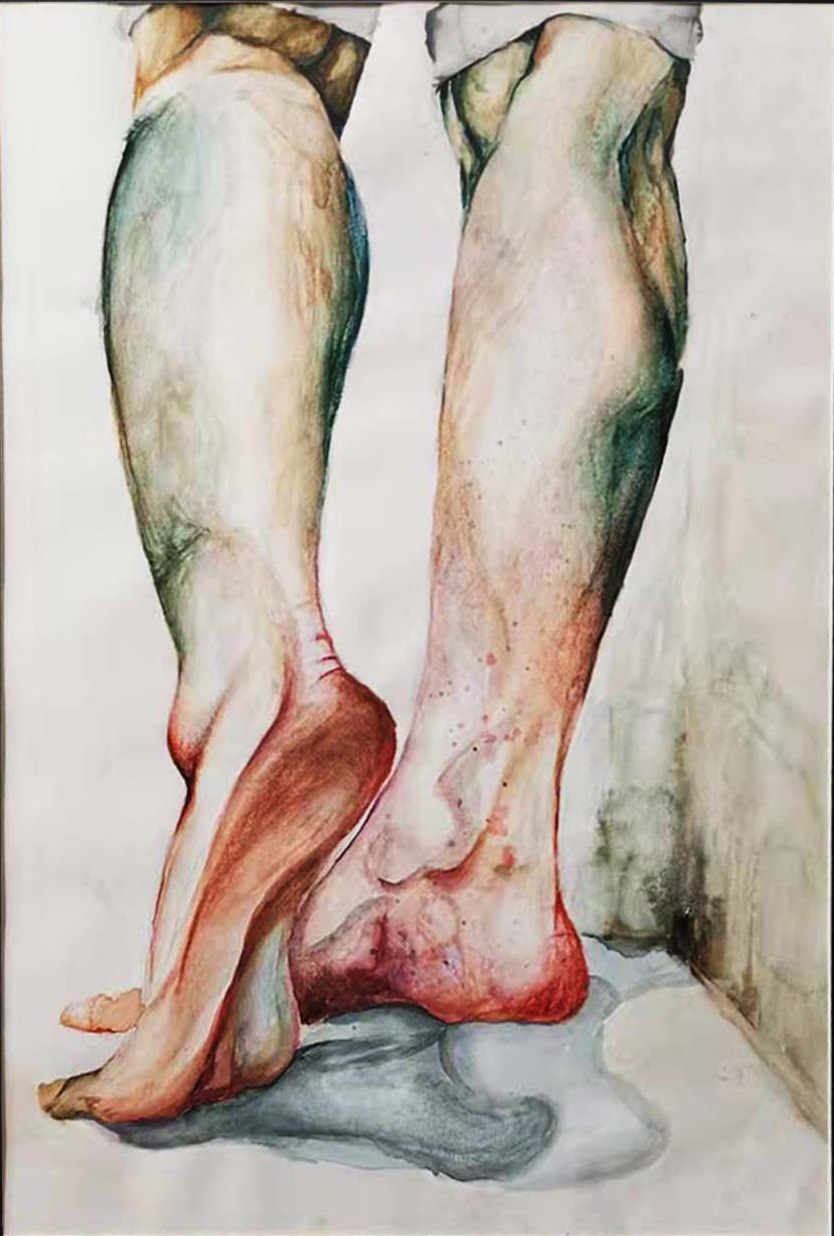

Medium seems inseparable from message in your practice—ballpoint ink, watercolor, oil. How do these materials shape the emotional tension in your work, and what draws you to them over digital or more conventional techniques?

Ballpoint ink’s permanence mirrors societal judgments—once marked, they’re nearly impossible to erase. In Limited Strength, its rigid lines reflect the inflexibility of gendered expectations. Watercolor bleeds unpredictably (as in Anchor’s capillaries), mirroring the body’s fragile resilience. Oil’s tactile layers (Vagabondage) carry the weight of memory. Digital tools lack this aliveness; traditional mediums breathe, stain, and resist—they’re collaborators, not mere instruments.

Anchor zooms in on your ankle, transforming it into a metaphor for endurance. Why that part of the body, and what does it reveal about the quiet, often overlooked strength you explore across your practice?

The ankle is an unsung hero—bearing weight, yet rarely celebrated. In Anchor, I magnified my own ankle to map its terrain: the blues of hematomas, tendon networks like root systems. This microcosm reflects macro resilience. We fixate on grand displays of strength, but survival often hinges on the quiet persistence of the overlooked. The ankle, like migration, demands constant recalibration—balance isn’t static, but a muscle memory of adaptation.

Your visual language sits at the intersection of surrealism and personal myth-making. How does this dreamlike approach help you confront the psychological aftermath of cultural dislocation and identity fragmentation?

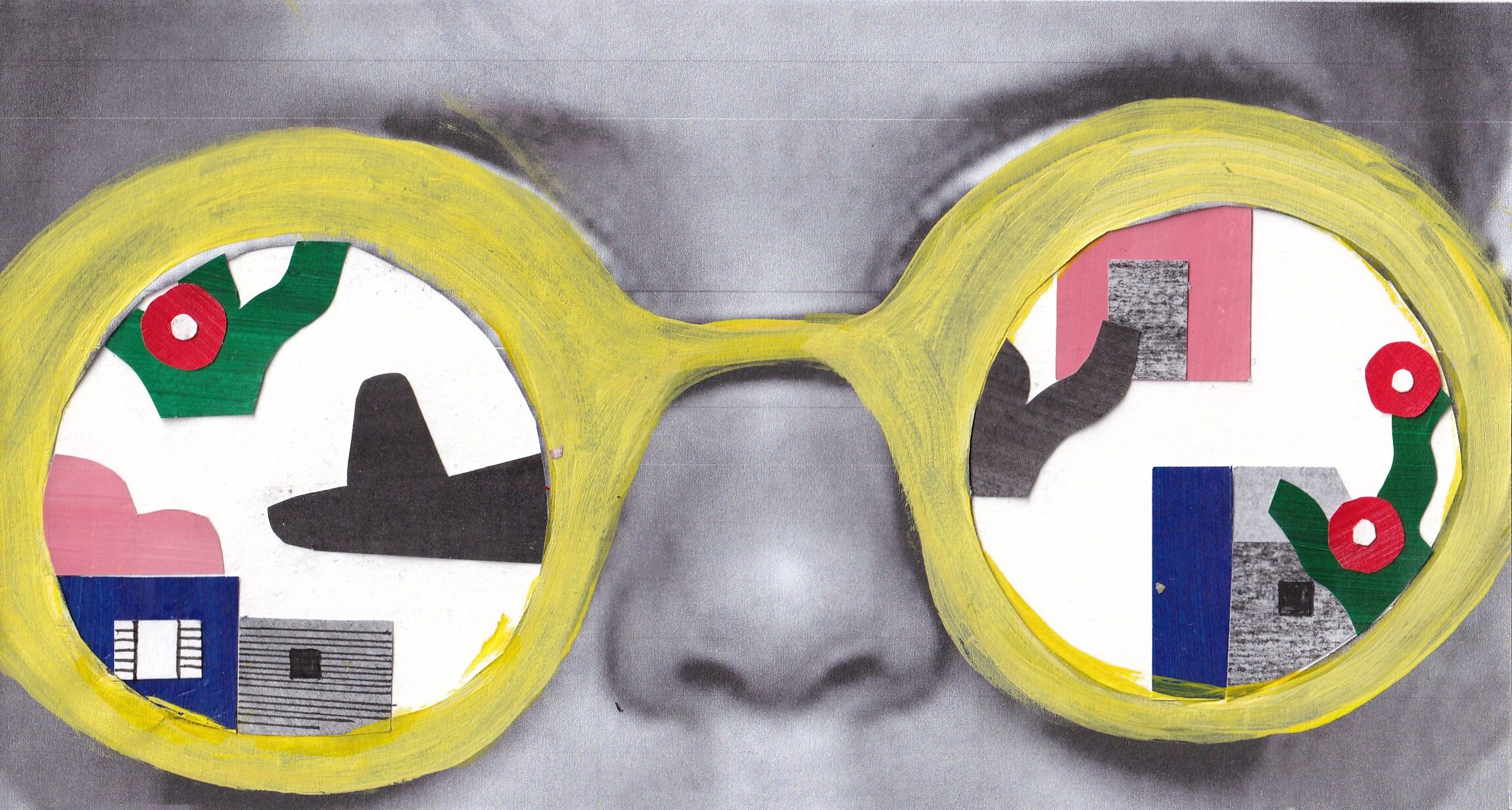

Surrealism grants permission to fracture logic. When I paint hair as both noose and lifeline (Escape), or collage WWII radio operators into AI-dominated landscapes (Lost and Found), I’m not escaping reality—I’m distilling its absurdities. Dislocation shatters identity; surreal reassembly becomes a coping mechanism. These dreamscapes aren’t fantasies, but emotional x-rays—they reveal the bones beneath the skin of “normalcy.”

As an artist shaped by China, the U.S., and now the UK, how has your evolving sense of ‘home’ influenced your creative voice, and how do you see your practice contributing to conversations around migration, memory, and resilience in a global context?

“Home” for me is a verb—an act of stitching roots from transient moments. My work (Lost and Found, Vagabondage) rejects the myth of seamless belonging. By layering materials—faded textures of dyed paper, WWII photographs, foam board’s honeycomb grids—I reconstruct the migrant’s patchwork identity. Globally, migration is often reduced to trauma porn or statistics. My practice insists on its complexity: it is loss, but also invention; rupture, but also rebirth.

The post Depicting the Unseen: Yiqi Zhao on Migration, Memory, and the Female Form appeared first on Our Culture.