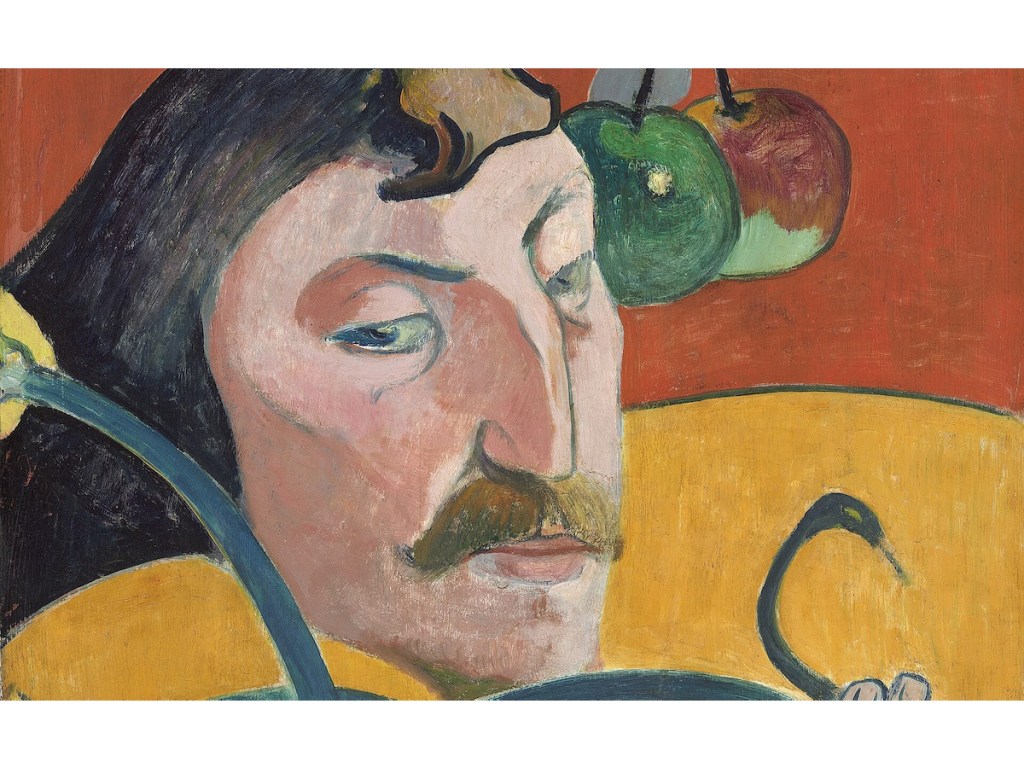

Do We Need to Vindicate Paul Gauguin?

Paul Gauguin frequently called himself a “savage from Peru.” Forget that he spent more time as a stockbroker in France than he did as a child in the Peruvian household of his aristocratic great-uncle, waited on by enslaved people. To indulge in the grand self-mythology he conjured up to accompany pieces like “Manaò tupapaú (Spring of the Dead Watching)” (1892), forget that.

Not until the 1970s did feminist and postcolonial critics experience what art historian Norma Broude called an “awakening.” Gauguin, his art, his lionized reputation as the modern primitivist, and primitivism itself as a movement faced a deconstruction so thorough that the 21st-century museumgoer usually knows at least two or three things about him. Namely: He was a French, middle-aged pedophile who preyed on, and reportedly spread syphilis to, 13- and 14-year-old girls in French Polynesia.

Is it time to reappraise?

Maybe, Sue Prideaux argues in Wild Thing: A Life of Paul Gauguin (2025), the first major biographical study of the artist in 30 years. More precisely, she writes, it’s time “to re-examine Gauguin’s life; not to condemn, not to excuse, but simply to shed new light on the man and the myth.”

Why now? Prideaux cites three reasons. A 2018 study carried out on teeth found at the site of Gauguin’s death (his “House of Pleasure” on the island of Hiva Ova) proved they were, with high probability, his teeth; they showed no traces of mercury or arsenic, minerals thought to be used as a treatment for syphilis at the time. The original, long-lost manuscript of Gauguin’s Avant et après resurfaced in 2020. And the Wildenstein Plattner Institute released its final volume of Gauguin’s catalogue raisonné in 2021.

Perhaps more tellingly, though, Prideaux wrote candidly in the Guardian in March that she felt she “couldn’t live in the dishonest and hypocritical position of loving the paintings and hating the man.” An uncomfortable dissonance familiar to many an admirer of many an artist, to be sure — and one that might spur a person to chart a path back to a comfortable equilibrium. But sometimes the concrete evidence needed for this redemption simply doesn’t exist.

This is not to say that Prideaux fails to rigorously analyze Gauguin’s life. Far from it. The report on Gauguin’s teeth, for example, lacks concrete answers on the syphilis question. It’s impossible to “confirm or deny,” the researchers write, whether he had or died from the sexually transmitted infection. But coupled with a recorded diagnosis from Gauguin’s doctor and visual connections between the rashes and sores induced by syphilis, eczema, and the bites of sandflies, Prideaux’s argument that it was simply a long-lasting rumor seems grounded in reality.

But the concern over whether Gauguin spread syphilis to teenage girls ceased to matter to me by the end of Wild Thing. Gauguin still had sex with and “married” several as a man in his 40s and 50s; abandoned his first wife and children to find societies untouched by the “civilization” he claimed to despise; and perpetuated colonial narratives that tie entire cultures to an open-handed sensuality, giving men like himself permission to indulge in violent sexual fantasies.

Prideaux straightforwardly acknowledges all of the above throughout Wild Thing. But so, too, does David Sweetman in his 1995 Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life, one of a few major biographies of the artist. Slight differences in access to materials don’t keep the two authors from coming to relatively similar, well-worn conclusions about retroactive judgment and the division of art and artist. (Reminders about the age of consent in France and its colonies at the time, 13, are peppered throughout both biographies.) For this reason, Gauguin’s “scandalous reputation” is not “largely undeserved,” as Prideaux’s publisher declares.

Rather, Wild Thing adds to the mix a slightly more charitable and compassionate study, rather than one that upends or transforms. It invites us to sympathize with Gauguin, and there are moments when Prideaux convinces us to — like in her fascinating examination of Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh’s turbulent friendship — just as Sweetman convinces us not to in the evidence he offers about Gauguin’s own contemporaries and their condemnation of his behavior. Where Sweetman sees in Avant et après an obsession with sex and a boastful, arrogant artist, Prideaux sees a man who “excoriates colonialism … pleading for greater justice and lower taxation of the indigenous people” and “silly stories.”

Both can be true. But Wild Thing‘s warm critical reception illustrates two things: the complex nature of Gauguin’s legacy and the fact that, in 2025, redemption arcs sell.

Wild Thing: A Life of Paul Gauguin (2025) by Sue Prideaux is published by W. W. Norton and is available online and through independent booksellers.