For Glenn Ligon, Language Is Material

The Brant Foundation’s Glenn Ligon isn’t a deep dive into the artist’s career, but it is a concise overview that does something rare: it gives the art space to connect with the viewer. The show’s eight works, all drawn from the Brant’s collection, are spread across four stories, two of which are dedicated to one installation each. Almost like a “greatest hits,” it includes stenciled text paintings, neon signs, and one video installation.

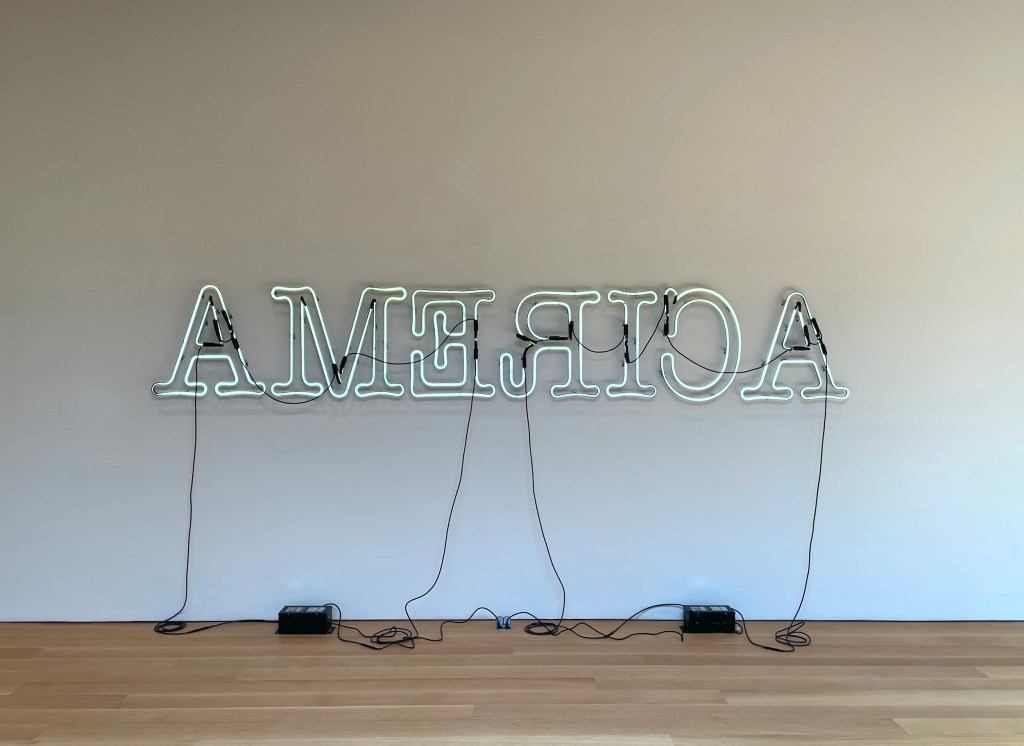

The staff suggests starting with the floor where text paintings are paired with one of Ligon’s best-known pieces, “Rückenfigur” (2009). The title refers to a device in art, most often associated with Caspar David Friedrich, of depicting a figure from behind, as a means for viewers to project themselves into the work and contemplate the scene. One obvious interpretation of Ligon’s piece — a white neon sign reading “America” with the letters backwards — in relation to the title, is of a White America that’s turned its back on everyone else. It’s a strong, direct statement, but the artist’s work lends itself to more than a single, straightforward reading. His use of language as a medium points up its failings as well as the viewer’s stake in what’s said and whether or not it’s legible to us.

A text painting on an adjacent wall alternates the names “Malcolm” and “Martin” in black on a red ground (“Deferred (Malcolm/Martin),” 1991). As the repetition transforms the names into sounds, they visually degenerate, becoming almost unreadable at the bottom of the canvas.

Other works take the limits of language further, including “Stranger #64” (2012), where illegible text from James Baldwin’s essay “Stranger in the Village” (1953) becomes a palpable object through layers of oil stick, acrylic, and coal dust. What’s initially an aesthetically enticing dark gray surface emerges as an unsettling embodiment of Baldwin’s story of the racism he encountered in a small, all-White town in Switzerland.

The outlier in the show is “Live” (2014), a silent seven-channel video installation screening footage of comedian Richard Pryor’s 1982 stand-up film Live on the Sunset Strip. Ligon has made text works based on Pryor’s material in the past, so it’s all the more disorienting to see him performing — here, fragmented, the different screens showing just his face, arm, torso, or crotch — without hearing him.

Even without the sound, anyone who’s familiar with Pryor knows that racism is a recurring subject of his comedy, just as it’s a through line in Ligon’s art. By breaking his image into parts, the artist may be alluding to the fragmentation and fetishization of the body that many people of color endure. But again, it’s not that clear-cut. We’re watching someone whom most people will recognize. Like the text paintings that communicate visually rather than verbally, through their formal breakdown or manipulation, “Live” shows Pryor’s act in minute detail, through expressions and body language that are often more resigned or pained than comedic.

For me, “Live” was the most infuriating and meaningful work in the show, a frustrated attempt at communication that actively involves the viewer. If you’re not interested in the comedian, you may watch for a few minutes and then walk away. But otherwise, how long can you stand to watch someone speak without hearing what they’re saying?

Glenn Ligon continues at the Brant Foundation (421 East 6th Street, East Village, Manhattan) through July 19. The exhibition was organized by the foundation.