Galleries That Play the “Responsibility” Game

You see it sometimes in blue chip galleries: shows that seem to be reaching toward something more akin to a museum exhibition, in which curation, contextualizing information, and objects play an atypically large role for a commercial enterprise. It feels like David Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth have made some of the biggest gestures in this direction over the past few years. In addition to exploring expansive bodies of work, it seems obvious that these efforts are aimed at adding weight and legitimacy to both the galleries and the work they sell. By creating an intentional simulacrum of a museum, they are ultimately saying, we can play this game too.

This desire to step outside of institutions while still modeling their behavior was at the top of mind when I walked into Mother Nature in the Bardo. On view at High Line Nine, an event venue that sits just below the High Line park in Chelsea, the exhibition was curated by Evanly Schindler, the founder and former publisher of BlackBook magazine. From Judd to Monet to Rauschenberg; from Kusama to Dali to gilt-framed works by members of the Hudson River School, including Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Cole, names we more often encounter at major art institutions cover the walls of this space. Alongside them are pieces by contemporary artists such as Ebony Patterson, Nicholas Galanin, and Serge Attukwei Clottey. But unlike in a museum, everything is for sale.

Hyperallergic readers will be well-versed in the fact that most museums are not, on the whole, benevolent institutions. A vast laboring class keeps them running, and many even manage to do great work, but museums’ reliance on excess wealth is just always going to lead to problems. Ultimately the commercial and institutional art worlds are not all that separate, with money, people, and artworks regularly moving betwixt and between.

Yet, it’s still notable that a commercial undertaking like Mother Nature in the Bardo works so hard to present itself with an institutional veneer, making claims that it “fosters a sense of shared responsibility” while exploring “the impact between art, culture, and the environment.” It also proclaims on wall texts and in the catalog its collaborative relationship with UNESCO (in fact, the agency’s Global Education Monitoring Report is an “impact partner” and will receive 10% of the profits from any sales).

Perhaps curator Klaus Biesenbach’s foreword for the catalog reveals a bit too much about who this show thinks it’s addressing as he recounts the impact of Hurricane Sandy on his property in the Rockaways: “Saturday night there was an evacuation order, and even I had to leave back to Manhattan.”

“…even I…”

Clearly, Biesenbach does not think he’s speaking to the thousands of inhabitants of the Rockaways who had no other place to go, like one of my colleagues at the time, her husband, whose business was washed away in the storm, and her two children, who all held out in a storm-damaged building for weeks after Sandy, without electricity, until they eventually became climate refugees, moving south.

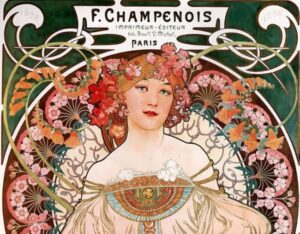

But even as this show and its catalog (which, bizarrely, for a book by a former publisher, is filled with pixelated and blurry images) seem to set themselves up as easy targets, they also hold up a mirror with their overreaching claims and wildly unaccountable content — seven of the eight catalog essays are by men, all are by contributors from the US and Western Europe, with virtually no meaningful acknowledgement of frontline communities in the Global South experiencing the most impact from climate collapse. By borrowing the costume of a museum exhibition, this show is a reminder that we should all be more critical of claims about what any exhibition, anywhere, is accomplishing in the world and exactly how it’s having an impact.

Mother Nature in the Bardo continues at High Line Nine (507 West 27th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through April 30. The exhibition was curated by Evanly Schindler.