How Painting Saved One of Our Most Iconic Designers

It feels impossible not to envy Peter Mendelsund — the man who can do everything, and well. Masterful designer of some of our era’s most recognizable book jackets. Lauded author of fiction, as well as books on graphic design. Creative director of the storied monthly The Atlantic. Accomplished classical pianist. And now, movingly expressive painter.

But as his new book Exhibitionist demonstrates to devastating effect, it was desolation that made him one. Depression during the pandemic brought him to the existential brink. As related in the journal entries accompanying lush reproductions of 100 paintings he made throughout this period, his state of mind grew dangerously bleak during his family’s sojourn at a New Hampshire farm. Variously angry — songbirds “never shut the fuck up,” he fumes, the sight of a heron only makes him “jealous of its stupid single-mindedness”; unable to eat or sleep; fretfully superintending a stash of painkillers and alcohol; and filled with self-loathing, he descends to abyssal depths.

The ladder appears in an unlikely place: the arts and crafts store Michaels. Without a plan, he finds himself loading his basket with acrylic paints and pre-primed canvases; next, he goes to the hardware store for less fine art-y supplies. He then repairs to an old barn on the rental property with only a vague notion of what to do, and even less knowledge: His wide-ranging education seems to have covered every subject but painting. Yet his resolution to try provides the avenue of escape from his beleaguered mental state: Only doing could propel him from incipient unbeing. He starts, and finally — “I had felt something while painting,” he writes. “What I felt was movement.”

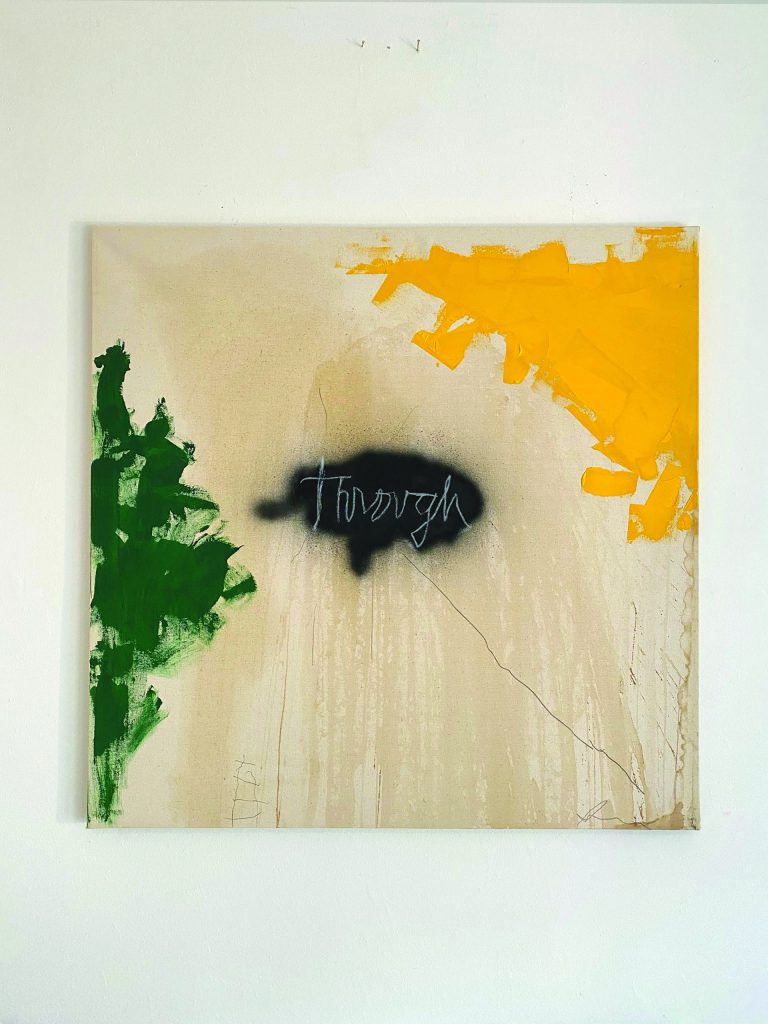

Fittingly, the works that result from this act of self-healing (although painting is far from reductively redemptive, as the journal also examines philosophy, music, literature, friendship, and a host of other searching subjects) are unconstrainedly gestural. Mendelsund’s version of action painting yields work in which acrylics are glopped on, squeegeed, worked over, left to the elements, and written on (using an extension or with his nondominant hand, to avoid preciosity). Other media include rainwater, which lends a delicate melancholy to the surface; coffee; whiskey; mud; spray paint; Sharpie.

Giving himself the freedom to explore without preconceptions or preconditions — he claims little familiarity with art history, although his oeuvre contains echoes of the giants of 20th-century art, from Klee and Miró through the Abstract Expressionists, with a final fillip of Basquiat — kicked something loose in Mendelsund. But it unleashed not only a generative creativity, but also a long-awaited reckoning with the dark memories of his bedeviling yet deeply loved father, also an artist.

“Depression is a language: frequently mistranslated,” Mendelsund avers. The paintings in Exhibitionist speak eloquently — and obstinately — for themselves.

Exhibitionist (2025), written by Peter Mendelsund and published by Catapult, is available for order online and in bookstores.