How the Motorcar Helped Fuel Feminism

ST. LOUIS — American car culture has long seemed synonymous with a particular make of men: showy, and yet unsure that they have something to show, as likely to ogle a woman’s figure as they are a curvaceous fender.

Roaring: Art, Fashion, and the Automobile in France, 1918–1939 flips that conflation between motorcar and machismo on its head — or shall we say steel or aluminum roof. Steering through two decades of the early 20th century, Roaring reveals how inextricably fine art, fashion, and automotive design were bound together to define the moderne. Arguably even more thought-provoking is how the era’s ardor for speed, movement, and individual autonomy not only informed the arts, but also carried subtle feminist implications. What if a looser skirt lets you Charleston a little faster? What if the drive for independence could be ignited behind the wheel?

At the exhibition entrance, we encounter a 1928 wooden Citroën coupe hand-painted by French-Ukrainian artist Sonia Delaunay, along with the marque’s promotional poster of two chic mademoiselles regarding a scarlet roadster. Across the gallery, a 1925 portfolio of Delaunay’s pochoir watercolors depicts a brigade of ladies in brightly colored activewear, leading to a vitrine containing an ensemble designed by French-Polish designer Sarah Lipska, who also did costumes for the Ballets Russes. This entry sets the stage for the next five galleries, each of which unfurls the surprising overlaps between fashionably zippy cars and the intrepid “New Woman” of the early 20th century.

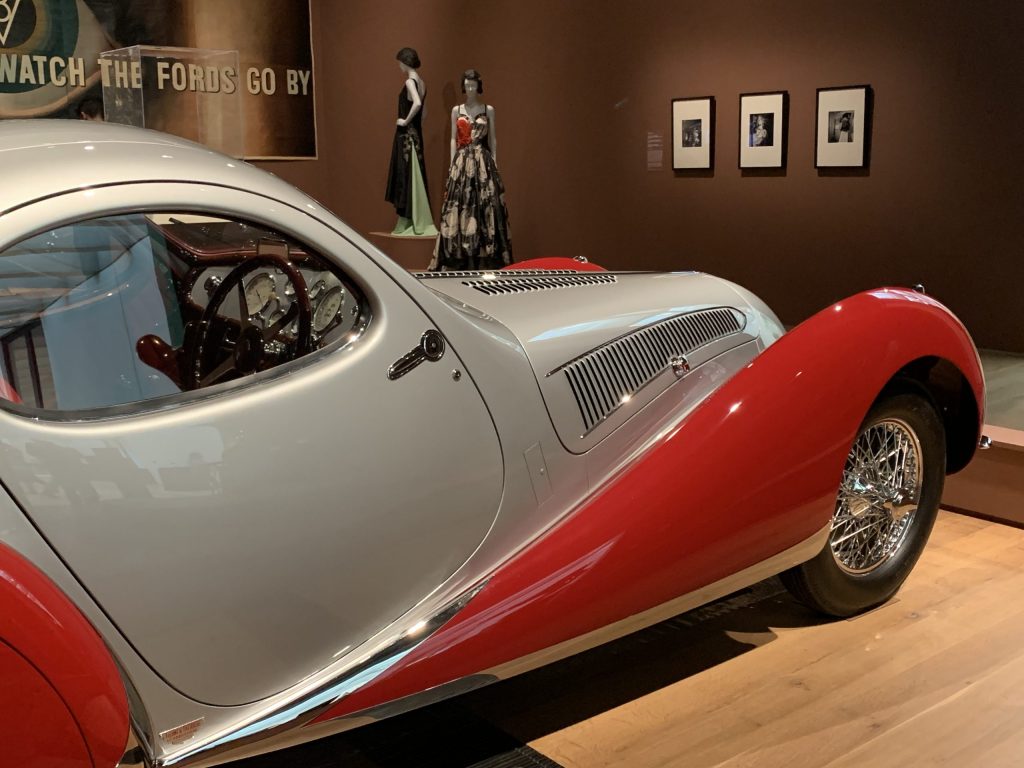

With 11 vintage vehicles on view — including no fewer than four gleaming French-designed Bugattis — autophiles will not be disappointed. And for those generally unmoved by the automotive, these objects serve as sculptural proof of a time in which automobiles were as much art as machine, in felicitous dialogue with apparel designed by the likes of Elsa Schiaparelli, Eileen Grey, Jenny Sacerdote, among other trailblazing women whose work was duly fêted at the 1925 Paris Exposition. As evidenced by the sumptuous garments on display, corsets and stiff fabrics were dropped for fluid silhouettes, ensuring maximal mobility; ornate embroidery was swapped for aerodynamic lines and Art Deco-inspired geometric patterns.

The penultimate section, titled “Women at the Wheel,” vrooms with the sound of “Bugatti Queen” car racer Hellé Nice swerving around a track before gaily lifting a trophy for at the Actor’s Championship Grand Prix. “Another Victory for Feminism,” reads the intertitle of the scene projected on the wall. Across the gallery, we see footage of Jazz Age entertainer (and car enthusiast) Josephine Baker presenting her onyx and emerald Delage D8-85 at a Parisian Concours d’Elegance (competition of elegance) in 1935 — a decadent affair for French socialites, often leashed to pulchritudinous pooches. Below the film stretches a similar model, a gleaming Delage D8-120, made two years later, inviting us to imagine the St. Louis-born legend alighting from its lavish cabin.

With its eclectic array of objects and triumphant joie de vivre, this is a show in which the art of curation impresses as much as any individual artwork — but never such that the conceit overshadows the beauty of what is on display. By the time I arrived at the final room — “Bodies Transformed,” lined with Lanvin gowns assembled around a 1938 Figoni Teardrop Coupe and 1937 Delahaye — I felt as if my own body was galvanized; I would never see its ability to zip and zoom so freely in the same way again. Nor would I neglect the automobile’s role as a symbol of agency and speed, no matter how much I prefer the stroll to the drive.

Roaring: Art, Fashion, and the Automobile in France, 1918–1939 continues at the Saint Louis Art Museum (1 Fine Arts Drive, St. Louis, Missouri) through July 27. The exhibition was curated by Genevieve Cortinovis with Sarah Berg and Ken Gross.