Internet Misinformation Is the New Medieval Magical Thinking

Iconophages: A History of Ingesting Images by Jérémie Koering is a dense, well-researched book on what seems, at first glance, a hermetic subject matter. It charts the history of rituals involving the eating and drinking of icons, or religious works of art, beginning in Ancient Egypt and continuing through the Byzantine Empire, Middle Ages, and even the 20th century. Dousing the Met Museum’s “Magical Stela (Cippus of Horus)” (360–343 BCE) and drinking the water that passed over it, for instance, supposedly cured venomous snake bites. (It didn’t.) But hidden beneath entertaining but obscure references to licking, bathing religious icons (and drinking the bathwater), grinding relics into powder and eating them, and other fun esophageal tales, is a story about the cultural evolution of the mind-body complex.

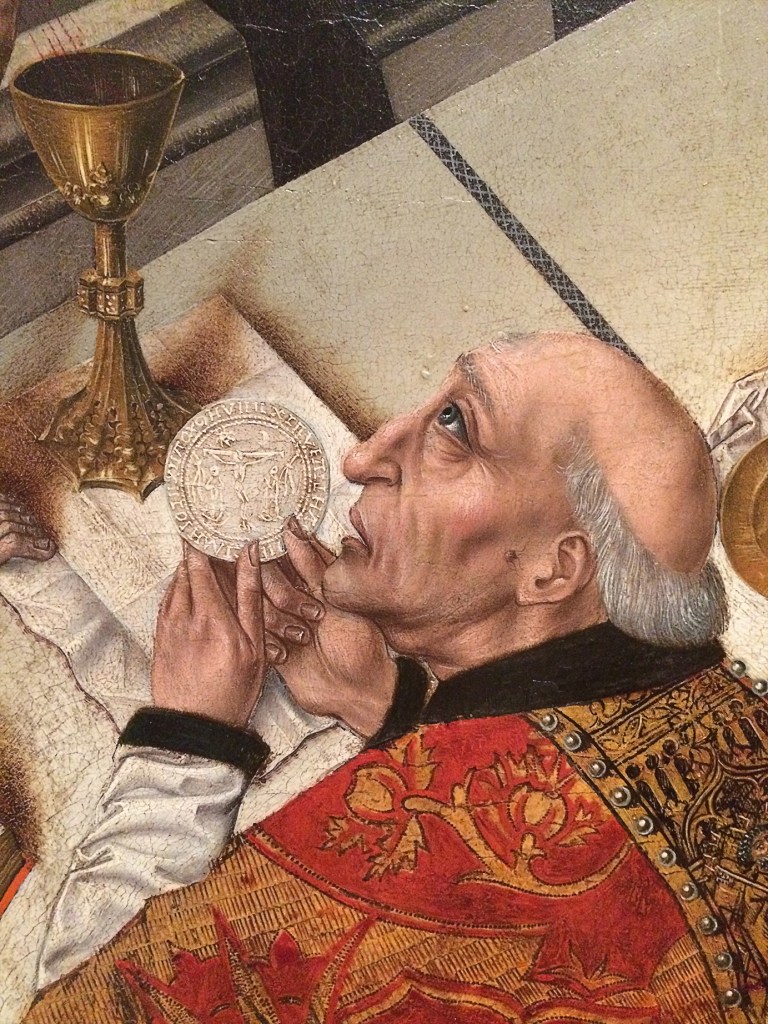

A significant part of Koering’s thesis is that in the pre-Christian era, such as in the ancient city of Byzantium, magic and religion were one and the same. According to this logic, the icon made visible the holy being, and ingesting it established a relationship between the consumer and the divine power, as well as membership in a cult of shared belief. Then, this consumption became symbolic. At the 1551 Council of Trent, the Catholic church adopted the ritual of eating a cracker as a symbol for the body of Christ, and the drinking of red wine as the blood of Christ.

This seems simple enough, but Iconophages is not an easy read. It is filled with primary documentation so detailed that it seems to lack a bigger picture — scores of pages delineating how the bloodstained shirt of Thomas Becket was soaked in water that was then used to cure a woman suffering from paralysis in 1170 Canterbury, or how small woodcuts illustrating the miracles by the Medieval jurist Giuliano di Francisco Guizzelmi were regularly placed in the mouths of the deceased to bring them back to life. The book is essentially a long, detailed list of such cases, and I found myself wondering what exactly all of this was meant to tell me about human desire. Are we just governed by the fear of death, and searching for an easy fix, even it obviously doesn’t work? Or are we simply a culture of simpletons? Still, readers might, like me, enjoy the gross and gory fairy-tale quality of it all.

The most relevant thing about Iconophages, however, is how a version of this ritualistic consumption has continued into our century. After Trump and his gang of irrational fundamentalists took command, I couldn’t help but read this book as a parable about his particular sphere of the internet, another site of fetishistic consumption filled with icons, as well as logos, emojis, memes — and fueled by the irrational and its symbolic transubstantiation into misinformation and lies. There, we find conspiracy theories about vaccines, climate science, dangerous “others”; there, the cult-like Make America Great Again movement assigns supernatural powers to Trump; there, a different form of consumption, such as the purchasing of iconic meme coins, promises a cure. Internet misinformation is a new form of medieval magical thinking, a populist version of dogma meant to assuage contemporary fears. If we are to learn from Koering’s historical examples, this form of magic never did prolong life or eliminate the plague. Rather, Ideological polemics — the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation — resulted in centuries of hostile feuding tribes. And here we go again.

Iconophages: A History of Ingesting Images (2024), written by Jérémie Koering, translated by Nicholas Huckle, and published by Princeton University Press, is available for purchase online and in bookstores.