Jackie Amézquita’s Baked Bricks Chart the History of Migration in LA

This past winter, Jackie Amézquita had several test bricks arranged neatly on a table in her studio in Los Angeles. In a departure from earlier work, each of these bricks, made with soil and masa de maíz (corn dough), had been inset with a mixture containing other organic materials—blue pea flower, cocoa, cochineal, charcoal, bee pollen, coffee beans, achiote—that gave them brilliant hues of blue and mauve or deep tones of ochre and black. That so many biomaterials are easily accessible in LA speaks to the city’s history of migration and the legacies of colonialism, Amézquita said.

She started using soil in her work after a performance in which she walked from Tijuana to LA over eight days. Every time she finished a bottle of water, she’d fill it with soil. By the journey’s end, she had collected some 18 samples—and began thinking about her findings as an archive and a site of memory. She remembers wondering, “If Earth could speak, what would it say? What stories would Earth share?”

Amézquita recalled the creation myth in the Popol Vuh, in which, after some trial and error, the gods used corn to make the first humans. To make her bricks, she freezes them to hold their shape and then bakes them in an oven for several hours, flipping them every so often in a process she compared to cooking tortillas on a comal. After they’ve dried and before a second bake, she takes them outside to receive some light. “I think of the sun as giving life and other energy to the work,” she said.

It took her about two years to perfect the balance in her soil-and-masa bricks, which have figured in multiple works, including her 2023 installation El suelo que nos alimenta. The wall-size piece, commissioned by the Hammer Museum for that year’s Made in L.A. biennial, comprises 144 square bricks made with soil from each of LA’s neighborhoods and incised with drawings representing different communities.

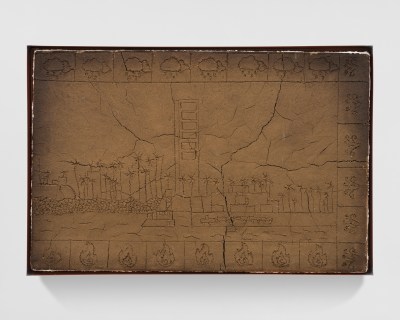

Jackie Amézquita: Oro Negro (detail), 2024.

Courtesy Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles

Her brick-related works also evoke the history of migration, which is a central concern to Amézquita’s practice—especially as it relates to her family. She moved to LA from Guatemala in 2003, following her mother, who moved in 1987. Her grandmother migrated from Mexico to Guatemala during the Cristero War in the 1920s and lost her most important documents along the way. “She had to start again from the ashes,” said Amézquita, who added that her grandmother’s resilience got her thinking: “How can we rebuild the pillars of histories that have been erased, trying to understand and piece everything together?”

Such questions inspired her to introduce charcoal and ash into her work, just before the wildfires in January ravaged parts of LA and severely impacted many of her friends. She sees them now as a metaphor for regeneration. “We’re still standing,” she said. “We’re still holding on. We can create something out of what was erased or destroyed.”