Jen DeLuna’s Blurred Paintings Bite

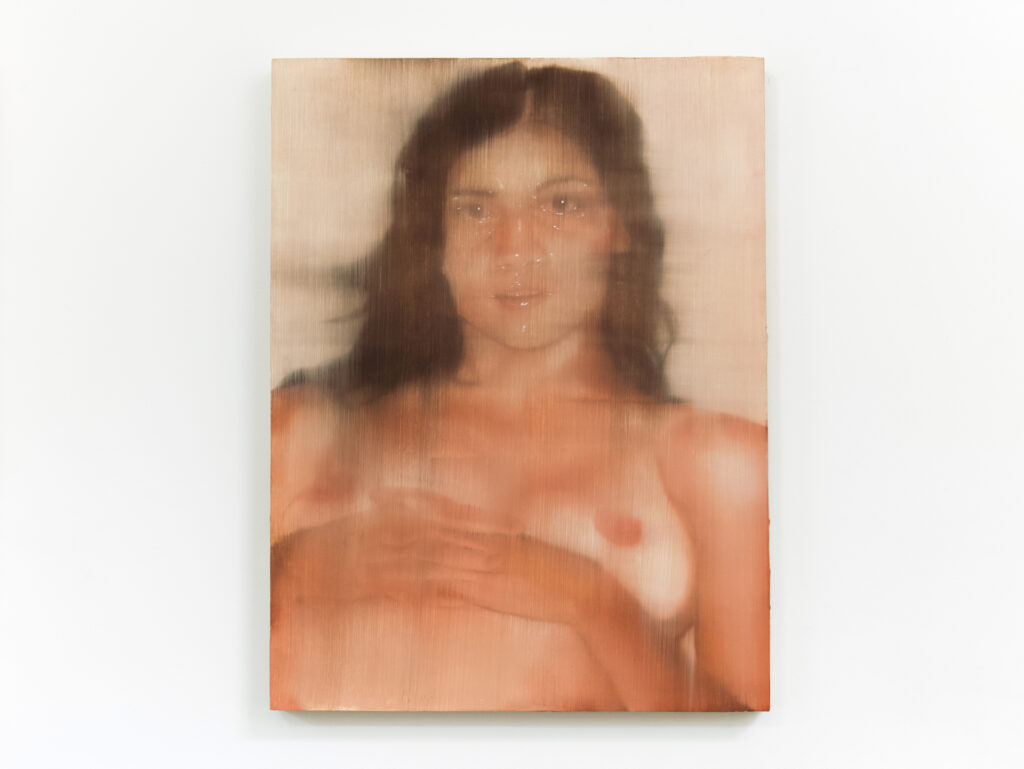

With the swipe of a huge brush, Jen DeLuna blurs her paintings before they can dry, freezing the image in a hazy moment. She describes the effect: “It’s like that feeling of memory fading, like something you can barely grasp.” Indeed, the works have a powerful feeling of uneasiness about them. Based on vintage found photographs, their combination of movement and stillness is inherently painterly.

“I would consider myself, first and foremost, a portrait painter,” she says, but DeLuna doesn’t know the identity of any of the women she paints. Many of the photographs she has used lately are images of ’70s pin-up girls, as in works like Rallying Sigh (2024). She zooms in on their faces or cropped parts of their bodies, removing them from any context but leaving the viewer with a strange sense of their commodified origins. “I like to be respectful to whoever this person is,” she tells me, which is part of why she calls her works “portraits,” despite their anonymity. Carefully painting someone’s face is “like falling in love,” she says, smiling at the cheesiness of her own remark.

I visited DeLuna’s studio while she was in residence at PLOP in East London. A massive painting of a slobbery, fanged, gaping dog’s mouth greeted me as I walked in. “This is the largest painting I’ve worked on, ever,” DeLuna told me. Going from a home studio in Boston to her own space for the first time has opened up new levels of scale. “I don’t think I realized how limiting my space was.”

The dog mouths are a new avenue for DeLuna. Like her portraits of women, they are blurred before highlights are added, giving a paradoxical finish that is both unstable and glossy. But the dogs are confrontational: They can be hard to look at for too long, their frozen ferocity leaping off the canvas. When I ask her about works like Hounding (2024), DeLuna talks about how dogs are associated with servitude and domesticity, but the underlying aggression of their animal nature never goes away. She always hangs them alongside her portraits of women. “There is a dialogue between them,” she says, “without being too prescriptive or too explanatory.”

DeLuna’s practice is refreshingly formalist and intuitive. She justifies certain decisions by deciding simply whether she wants, or doesn’t want, to do something. Others have called her work “glamorous” or “violent,” comparing it to fashion photography, Gerhard Richter’s work, and plenty more. She finds describing it herself much harder. “To imbue so much meaning into my work feels so decadent,” she said. She had never seen Richter’s blurred photo works, or painters with styles like hers, before developing her own practice as a BFA student at Carnegie Mellon University. Now, she says, all she sees online is work that looks like hers, because “that’s how the algorithm works.”

On their own, DeLuna’s renderings of women and of dogs are striking: Her method of painting creates a magnetic final product that invites prolonged looking. But hung together, the works are staggering. They force us to confront the violence inherent in the way we look at women, a menagerie of eyes and mouths evoking carnality in jarringly different registers.