Jordan Wolfson Makes Puppets of His Viewers with a New Work in Basel

In the middle of a room full of working people, there’s a large bird cage-like structure made of cameras and cables. Someone is inside of it; a flash goes off. Just next to this structure there’s a dummy similar to the kind used in crash tests. On both sides of the room there are four plots marked out with black tape. Inside each plot, couples wear VR goggles. They walk backward and forward with their arms stretched out, and are being directed by assistants in black.

This is your first introduction to Jordan Wolfson’s new work, Little Room, at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland. This VR work requires two people to have their bodies scanned—though how exactly this scan will be used within virtual space is not made explicit at first. The wall text reveals little, telling viewers that what they will experience will be “morally and emotionally challenging.” With Wolfson, this disclaimer comes as a matter of course.

Wolfson made his name in the 2010s with puppets, violence, and controversy. Female Figure (2014) featured a sexy animatronic witch who danced in front of a mirror, locking eyes with her audience through the glass. Colored Sculpture (2016) was a nasty little boy doll repeatedly hurled at the ground, and Body Sculpture (2023) took the form of a titanium cube with exquisitely articulated arms that appeared to touch itself, even mime, in its own cube-way, cube-suicide. Little Room is an explicit mix of tactics derived from Wolfson’s puppet-centric art and one of his most iconic works, the VR piece Real Violence (2017).

In that work, the audience member is dropped into an urban setting on a sunny day. The stillness is interrupted by the appearance of two characters, Wolfson and another man, who is kneeling on the ground, holding his hands up in a pose of supplication. Wolfson is holding a bat. He begins to beat this man to death in front of you. Blood splatters. Recalling the controversy that followed this piece at the Whitney Biennial, I approached Little Room with trepidation.

Installation view of “Jordan Wolfson: Little Rooms,” 2025, at Fondation Beyeler, Riehen, Switzerland.

©Jordan Wolfson. Courtesy Gagosian, Sadie Coles HQ, and David Zwirner

The process of being scanned, while similar in its gestures to going to the doctor or through the security line at an airport, is the first movement into another reality. Like an initiation rite, the piece begins with crossing a number of thresholds. The first threshold is finding a partner. Fortunately, I was quickly paired with another lone viewer, an artist with elfin features. “We’re about to get very intimate,” I told him. I had no idea.

We were told to get ready to enter a full-body scanner, and that our silhouettes would be very important. Near the queue, there was a simple black vanity with a double-sided mirror, wipes, hair ties, and tape, as well as baskets for personal effects. People wearing long dresses or skirts were encouraged to put on a pair of grey sweatpants. I was instructed that I should tie my hair back by an assistant who was in the middle of taping someone’s flowing culottes tight at the knee. I was then passed off to the next assistant who was in charge of taking the scan. A platform inside the cage calibrated and raised itself slightly, responding to my measurements. Inside the cage, many cameras were pointed at me. I was told to prepare for the flash.

After our respective scans my partner and I sat at a table and made small talk as we watched the room for clues of what we were about to experience. In a square in front of me a man and a woman have begun the experience, their eyes obscured by the heavy VR headset. They had just finished the calibration. The woman suddenly stepped back, startled, and began to laugh, then to cry. An assistant put a pair of headphones over her ears while she wiped a tear with the bottom of her T-shirt. It dawned on me, too late perhaps: she was reacting to herself. Wolfson had made puppets and animators out of each of his audience members by having each couple don each other’s skin.

Installation view of “Jordan Wolfson: Little Rooms,” 2025, at Fondation Beyeler, Riehen, Switzerland.

©Jordan Wolfson. Courtesy Gagosian, Sadie Coles HQ, and David Zwirner

When Real Violence premiered at the Whitney Biennial, the piece sealed Wolfson’s reputation as an edgelord. Wolfson insisted that this work and others were not political, that his art was just about violence (despite the fact Real Violence did contain one culturally specific element: Hanukkah prayers that figured prominently on its soundtrack). Given the nationwide movements against gender- and race-based violence and a focus on representation and identity politics that defined the 2010s, his refusal to have his work answer to those terms cast him as a provocateur. Yet it was a role Wolfson seemed to play with pleasure.

Post-pandemic, amid another Trump presidency, it’s difficult to find his edgelord persona quite so sexy or subversive—there’s enough to fear between the rise of the alt-right, ICE, and so much else. The mid-2010s were about debating what violence was—a microaggression, an artwork, a cop wrapping his bicep around a Black man’s throat and choking him to death. By 2020, the terror of fascism and genocide had reached a fever pitch, changing that discourse entirely.

If Wolfson is such an artist of his time, what is he now? I wondered this to myself as a headset was placed on my head. A white void, lined with a grid that seemed to stretch into infinity, began to appear. My partner in this piece was told by an assistant to calibrate the headset by walking and flipping his palms so that my skin can fit itself to his body. There were technical difficulties. The anticipation was difficult to bear. I had always been curious to know what it is to see myself as others do. The opportunity to do so had finally arrived, and I realized I was frightened.

My hands appeared before me with hair on their knuckles. Glancing down at myself, I saw my partner’s clothing: a striped shirt, beige pants, white sneakers. A figure—myself—appeared in my periphery. She was there, her eyes wide fixed in a bloodshot demonic stare, glitching, body folding and unfolding. Without meaning to, I said the word “stop” out loud.

From the hips down I was quite distorted, shorter and wider than I am, with very small feet. I tried to look up my dress, but it didn’t work. I couldn’t take my eyes off her, even as I wanted to flinch. Then a rectangular mirror appeared in the void. I could see myself wearing my partner’s skin. His face and gaze were all wrong, and I couldn’t get his arms to work, sometimes they disappeared completely. I tried dancing, and his body shuddered.

Male and female voices began chanting a poem with flat affect. My mouth was opening and closing to match its words: “God molested you.” The word “transparency” chimed as I looked down at myself in my partner’s body, seeing empty space ringed by the outline of his pants and sneakers. The mirror flipped, passed through us, and we followed it. There was a phantom feeling of touch as I skimmed my hand over the surface of the mirror, like trying to grab a beam of light. The poem continued: “Look at your hands, I love you. Look at your hands, I hate you.” We circled each other in that timeless void. The VR goggles suddenly began streaming reality. It was over.

After removing the VR headset and the headphones, my partner and I sat down and drank a glass of water. “You have spots,” he said, and I rolled up the sleeve of my sweater, which I had taken off when I was scanned. I looked at my own freckles, a bit dazed. I realized my internal monologue had gone completely silent during the duration of the experience, and in the moments afterward had to readjust to hearing my own thoughts again. My partner’s experience wasn’t as absorbing. The audio in his headset was broken—he hadn’t heard anything.

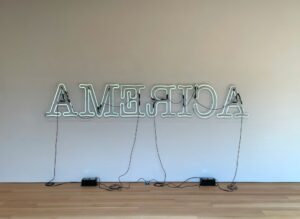

Jordan Wolfson, Little Room, 2025.

©Jordan Wolfson. Courtesy Gagosian, Sadie Coles HQ, and David Zwirner

It turned out that the body-switching experience made for a good bonding moment. My partner-in-art and I spent the next few hours wandering around the Beyeler talking about the work. The intensity of the experience, like a physical glow, eventually sloughed off, along with any frustrations with technical frictions. What remains are strong images of encounter, as when that twitching, uncanny body of mine appeared, followed by the moment I saw his face on mine, stiff, carved, and distorted. I’ve been left with a new memory.

Little Room could easily be read as an overly self-referential work, remixing the most obvious mediums and thematic aspects of his practice. But what makes this piece an elegant continuation of his body of work is that it is a quiet, compelling response to the criticism he received over the years. In Little Room, he tries to solve a problem: can the artist skirt the moralistic demands of representation?

Wolfson has often used white characters—including versions of his own body—to create supposedly apolitical scenarios in which violence isn’t racialized. But by putting the bodies of audience members into the work, something hyper-specific is achieved.

VR has often been touted as an “empathy machine,” with the potential to create understanding and care across disparate groups, as anthropologist Lisa Messeri noted in her recent book In the Land of the Unreal. It seems too neat to think that Wolfson has used VR in this way. Rather, with Little Room he seems to give imagined critics exactly what they want—not to think of the artist anymore, of what anything represents, but to experience themselves, that entity we are all obsessed with. As for your role puppeting the Other, good luck with that burden, because it’s not on Wolfson anymore. If there is violence in that room, it’s something you brought with you. Can you handle that?