Juneteenth Is the Story of a Freedom Withheld

When the Union Army arrived in Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865, it brought with it General Order No. 3 — news of emancipation that had been technically in effect for more than two years. For many enslaved Black people in Texas, that day marked the first official recognition of a freedom they had never been allowed to claim.

Barney and Hester Smith, an elderly couple later interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project, recalled the moment with quiet clarity. “Old master didn’t tell us,” Hester said. “We just heard from others. Then the soldiers came and we left.” Barney, once forced to walk cattle from Texas to Louisiana and back, remembered the disbelief: freedom had come, but with no land, no money, no home.

Juneteenth, in that sense, was never just about liberation. It was about the delay. The gap between law and reality. Between what was promised and what was delivered.

The 2021 federal recognition of Juneteenth was framed as a sign of progress. But for many of us, it felt like another delay in new packaging. A day off for federal workers and corporate employees, many of whom were never touched by the legacy it commemorates, while those of us still bearing its weight are handed a symbol in place of something structural.

Because emancipation didn’t come with a paycheck. Or land. Or protection. It came with an absence, and in that vacuum, Black communities did what we’ve always done: We built systems to care for ourselves. Mutual aid societies. Churches. Co-ops. Cultural spaces. These weren’t nonprofits. They were infrastructures of survival, resistance, and self-determination.

Today, that legacy continues in the arts. You see it in peer-led grant pools, pop-up exhibitions, artist barter economies, and community-led education. But despite this ingenuity, the dominant art world still replicates the logic of extraction. Black, queer, disabled, and working-class artists are continually invited to be visible — but not paid. Platformed, but not protected. Our labor fuels institutions that rarely acknowledge our right to own, direct, or even survive off what we create.

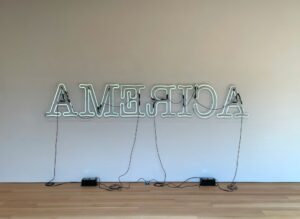

This isn’t slavery. But it’s something else that’s learned how to dress like freedom.

The plantation economy didn’t disappear — it put on a blazer.

The Cost of Prestige and the Price of Erasure

Take Brooks Brothers, one of the oldest American clothing brands. Its early fortunes were built on producing cheap, durable garments for enslaved laborers. That fact rarely appears in its marketing. Instead, it celebrates its heritage as the choice of presidents, financiers, and Ivy League elites. In the luxury sector, history becomes a value proposition — as long as it’s the right kind of history. Prestige is built by laundering the past, turning lineage into leverage while scrubbing out the violence that made it possible.

This same laundering happens in the art world. Institutions rush to platform Black artists while often avoiding any real conversation about how value is created, and who has access to it. Trauma becomes a curatorial talking point. “Equity” becomes a grant requirement. However, the underlying structure — the one that exploits artist labor while marketing itself as inclusive — remains untouched.

This laundering isn’t just historical — it’s aesthetic. It filters the images we’re shown, the stories we absorb, and the spectacle that too often gets mistaken for justice. You can see it not just in the past, but also in the way Black life is represented across contemporary visual culture. In Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death (2106), Arthur Jafa weaves together scenes of Black triumph and Black trauma, underscoring how visibility and vulnerability are so often collapsed into one, with no guarantee of care or consequence.

The work is mesmerizing, but it also indicts. It reminds us that Black representation is not equivalent to Black liberation. And in the art world, as in America at large, spectacle is welcomed more readily than structural change.

But redistribution doesn’t always come without conditions. Philanthropy has always played a complicated role in Black resistance, offering resources with one hand while reshaping the terms of liberation with the other. In the 1960s and ’70s, institutions like the Ford Foundation backed Black cultural work under the banner of civil rights and community uplift. But those grants often came with quiet expectations, steering movements away from radical self-determination and toward state-sanctioned notions of visibility, economic growth, and cultural legitimacy.

In Top Down: The Ford Foundation, Black Power, and the Reinvention of Racial Liberalism, historian Karen Ferguson shows how Ford’s investments in “Black empowerment” worked to neutralize the Black Power movement’s most transformative aims. By prioritizing bureaucratic infrastructure over grassroots organizing — funding intermediaries and nonprofits instead of liberation schools or assemblies — Ford helped reroute radical energy into administratively digestible programs, severing many movements from their militant roots.

That same tension haunts the arts today. When institutions built on capital extracted from slavery now underwrite artist grants or sponsor museum exhibitions about “equity,” we have to ask: What is being funded, and what’s being made impossible?

But if funders shaped the limits of past movements, artists have always expanded the possibilities of the present.

And yet, artists are already building something different. Something reparative. Something real.

What Artists Already Know: Building Power Without Permission

Artists have long developed strategies to reroute the flow of value. Alex Strada, for instance, has modified standard resale agreements to embed redistribution directly into the art market. Her contracts stipulate that any profits from the resale of her work must be used to acquire artwork by women and underrepresented artists, ensuring that value generated by her practice doesn’t get hoarded but reinvested.

Cameron Rowland offers another lens — one that makes the inaccessibility of reparations structurally visible. In Disgorgement (2016), Rowland established a Reparations Purpose Trust comprising 90 shares in Aetna, a major U.S. insurance company that once issued policies on the lives of enslaved individuals. The trust stipulates that these shares cannot be liquidated unless the federal government formally implements a reparations program. If and when that happens, the shares will be sold, and the proceeds will go directly to the federal agency responsible for distributing reparations.

Until then, the wealth — like so much historical compensation owed to Black communities — remains inaccessible, legally and conceptually locked away. The trust is not a metaphor. It’s mechanism. A sculptural structure that critiques both the accumulation of capital from slavery and the impossibility of reclaiming its full cost under the terms of the current system.

And here’s the quiet cruelty: Aetna is not alone. JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Bank of America — these financial giants built portions of their wealth by underwriting slavery: financing plantations, insuring enslaved people as property, and investing in the economies that profited from bondage. Today, their philanthropic arms bankroll artist residencies, museum exhibitions, and cultural programs. The money circulates through the art world, often without acknowledgment of its origins. Their money moves through the very systems artists depend on for visibility and survival, usually without any mention of where that wealth came from. Disgorgement doesn’t just indict one company; it forces us to ask: What does it mean to build an artistic practice inside a funding ecosystem that still profits from what it refuses to repair?

The abovementioned banks are now celebrated as patrons of the arts. Their logos are printed on museum walls. They headline art fairs. They underwrite biennials, fund curatorial positions, and buy naming rights to education wings. This is what cultural laundering looks like: the rebranding of racial violence as civic generosity. And still, the artists whose communities bore the cost of that history are routinely asked to donate their time, waive their fees, or be “grateful for the exposure.” The wealth is visible. The redistribution is not.

As Saidiya Hartman writes in Lose Your Mother (2006), “The afterlife of slavery is not a metaphor.” That afterlife is material, measured in housing segregation, wage theft, surveillance, and cultural extraction. It is also aesthetic, embedded in how Black pain becomes a commodity, while Black autonomy remains unfunded. Juneteenth doesn’t mark the end of that story — it reminds us that freedom, once delayed, must be defended on every front.

If Rowland critiques the inaccessibility of justice, and Strada offers a pathway to redistribution, then Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) provides a mechanism for enforcement. Founded in 2008, W.A.G.E. created a certification system requiring nonprofits to pay artists based on budget size. It’s a scalable tool that exposes how often artists are expected to subsidize the institutions they sustain. But to shift the system, funders must require — not just recommend — its use.

Together, these three approaches — Rowland’s structural critique, Strada’s contract-based redistribution, and W.A.G.E.‘s labor enforcement model — form a composite toolkit for artist equity. But to transform those tools into systems, we need to think bigger.

That means shifting not just how artists advocate, but also who is accountable.

Enter the logic of “wage-shifting”: reallocating the burden of artist pay from under-resourced organizations to the funders, institutions, and philanthropic bodies that hold the wealth. If you can require a land acknowledgment or an anti-racism statement in a grant application, you can require a commitment to pay artists. If you can fund a curatorial fellowship, you can fund the labor of those whose work fills the galleries. Equity isn’t an aesthetic. It’s a budget line. And accountability shouldn’t be optional.

We’ve been here before. Juneteenth isn’t only a marker of what’s been withheld — it’s a reminder of what we’ve already made, the futures we’ve long been practicing.

After emancipation, Black mutual aid networks emerged to fill the gaps left by government abandonment, including burial societies, land trusts, cooperative farms, credit unions, and freedom towns. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Panther Party’s survival programs expanded on this lineage, offering free breakfast for children, medical clinics, and educational initiatives grounded in political consciousness and community needs. These weren’t charity. They were systemic correctives — artist-designed, visually resonant, and politically functional.

That spirit didn’t disappear — it evolved. Now in its 20th year, The Laundromat Project stands as a model of the kind of artist-led, community-rooted infrastructure Juneteenth asks us to remember. Built on the belief that everyday spaces — such as laundromats, sidewalks, and front porches — can be engines of cultural exchange, The LP supports artists of color in embedding their work where they live, not just where they exhibit.

Like the Panthers, like the freedom towns, The Laundromat Project proves that we don’t need permission to build power — we just need proximity, practice, and the will to redistribute.

So let’s stop mistaking visibility for value. Let’s call unpaid opportunities what they are: exploitation dressed up as exposure. If we are serious about equity, then artist fee transparency must become the norm, not the exception. Contracts should reflect our communities, not just markets. Funders must be held accountable — not simply for what they say they support, but for what they materially sustain. Freedom isn’t granted through gestures. It’s built through structure. And it’s defended, again and again, by those willing to insist on more.

Juneteenth was never about what we were given. It was always about what we claimed. It still is. And this time, we’re not waiting.