Louise Bonnet Wants You to Feel Her Paintings in Your Bones

In her cartoonish yet sophisticated paintings of people, Louise Bonnet toes lots of lines—between familiarity and misrecognition, seduction and ick. Speaking of toes, she is especially skilled at painting big ones, those underappreciated appendages that allow us to stand upright and thus, according to Georges Bataille, be human. Pisser Triptych (2021), which featured in the 2022 Venice Biennale, boasts an overlapping set of feet painted in incongruous scale, as if belonging to different humanoid species: a small set of big toes are jammed into a fleshy, larger pair. In Kneeling Sphinx 2 (2021), clenched, extra–long toes indent a squatting woman’s rump.

Bonnet’s paintings feel true to life, though not because they are rendered with accuracy. Rather, her strategic exaggerations deftly capture the ways that bodies are sites of both pleasure and discomfort, how they can disgust and also delight, can feel alien yet also like home. Acknowledging all of that simultaneously is what makes her work refreshing and rare.

The Los Angeles–based Bonnet takes on the female nude—art history’s favorite subject, and feminism’s most debated—and transports her to a fantasy world, where she is blissfully free from both moralizing and misogynist ideas of how she “should” be. Her body is her own—often appearing to burst out of the canvas’s rectangular confines, her flab and rolls shiny and supple—but this doesn’t always mean her corporeal experience is pleasant. Itchy awkwardness is palpable; mysterious bodily fluids abound.

To discuss Bonnet’s latest work, we met up ahead of the opening of her two-person exhibition at the Swiss Institute in New York, a duo show with Elizabeth King titled “De Anima” that focuses on a shared affinity in both artists’ approaches to figuration, centered simultaneously on objecthood and liveliness. Complementing Bonnet’s cartoons are King’s uncanny wooden dolls. The two had been working in dialogue for a year or so, but after Bonnet lost all the work she’d made for “De Anima” to the LA fires in January, she started again from scratch. Meanwhile, SITE Santa Fe International commissioned the artist to create a new series for the next edition of the biennial, opening in June. We discussed both bodies of new work below.

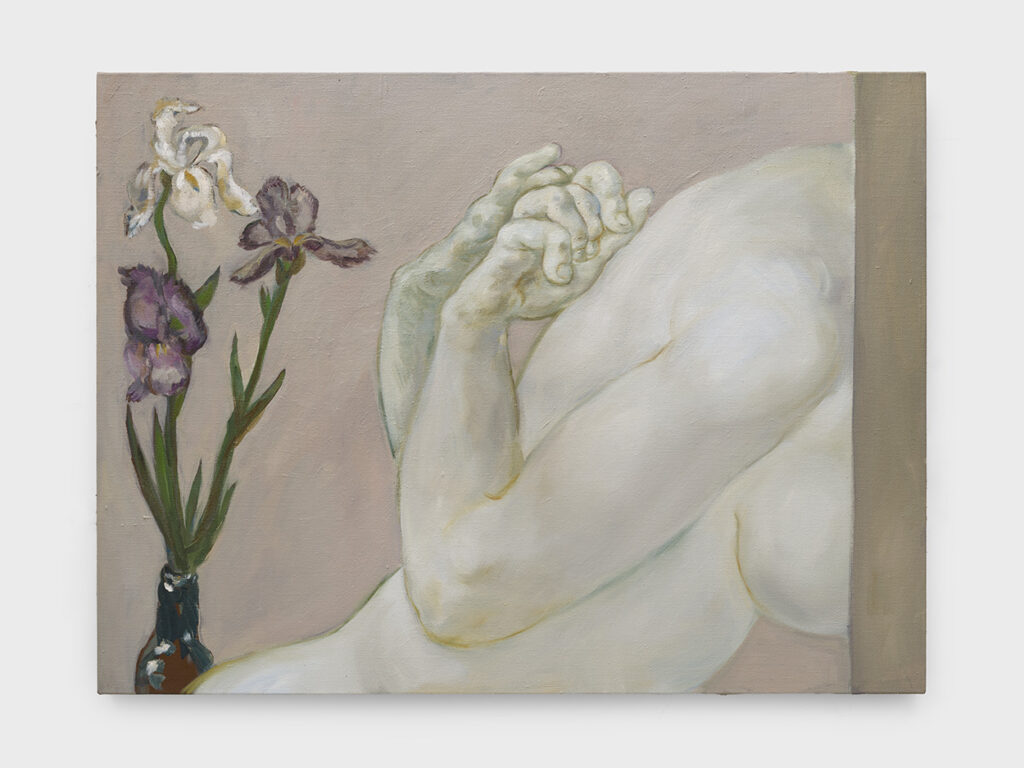

Emily Watlington: The first thing I noticed in your paintings at the Swiss Institute is that they are closer crops; in previous work you often showed the full figure, but here you are focused specific body parts.

Louse Bonnet: I really wanted to emphasize gestures that are routine but that we might not be totally aware of, or see ourselves doing. One is called Shoelace, another is Bra (all works 2025); they show people tying and fastening, but the garments have been removed. I imagined explaining these movements as if to an AI or an alien—or even to a man or someone who doesn’t wear bras! I was also reading about British spies who, during World War II, learned various gestures so that they might pass as French. They would parachute in, then hide their parachute really fast, and then walk down the road as if they were French. They’d eat garlic chocolate so that they would smell French. They re-sewed their buttons in the French style rather than the British. They never put their hands in their pockets.

I also painted walls and screens and doors in order to emphasize that you are seeing something intimate, peeking in. I’m always thinking about movies, and with this work I kept picturing a scene in Rosemary’s Baby—which I’ve seen a thousand times—where she’son the phone sitting on the bed, and it’s shot from behind the door, so that she’s hidden.

EW: You have a way of mashing together pop cultural references and art historical ones rather seamlessly—and yet there is a productive awkwardness to the amalgamation, too. I know your background is in graphic design. What got you interested in the more painterly, art historical realm?

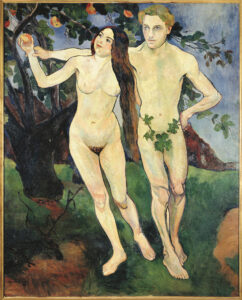

LB: I’ve always been interested, but I guess I got better at being able to paint. All the plants in these paintings come from the Garden of Eden, like figs and lilies. It’s more an art history version of the Bible than it is about following the text. The figures in my paintings in the Garden of Eden and so they are naked; their garments are missing.

EW: Naked and without shame—that makes sense, because to me, your paintings take on the female nude and bodily grossness while avoiding shame or moralizing. I’m curious about the proportions, like the huge foot in Shoelaceand the tiny foot in Shoe.

LB: I wanted to try making the shape kind of abstract, especially with Shoe. I also worked from pictures for these paintings, which I never do. I noticed I was starting to basically copy the picture, and I wanted to fight that.

EW: The heavy top figure with the small foot really captures the feeling of wearing heels and wondering if you’ll topple over. You’ve talked before about being drawn to the unidealized proportions of Manet’s Olympia.

LB: Yes, they’re why I think that painting is so great: something’s wrong in it. Another painting [of mine] is called Zipper, and I was hoping that you might recognize the gesture maybe not with your eyes but with your body or muscle memory—like when you see someone scratching and you want to scratch. Bodies know things.

EW: Your paintings are always of women, or else ambiguous.

LB. I think of it really as painting myself. I don’t know how it is for other people, but I’m not always looking at myself and thinking “woman.” Still, I don’t have a penis, so I don’t know how to paint from that experience. I can only speak to what I feel.

EW: That makes sense: you’re more interested in embodied experience than in women or identity. The female nude has a lot of art historical baggage, which you seem to joyfully disregard.

LB: In the end, if the work is “about” women, it’s not because I’m making a statement. Any social agenda that comes through is an accident. And I’m glad to not to be thinking about what I “should” do in my work. Instead I am interested in thinking about the sometimes arbitrary things we consider acceptable to show and not to show. I was reading a manual for manners from a few centuries ago that said you can blow your nose in your hand, but only if you don’t look at it.

EW: That reminds me of what Julia Kristeva says about the abject—that few things are inherently abject, but they become so when they are out of place. Hair, for instance, can be lovely when attached to someone’s head, but is considered gross once detached. You’ve talked before about being drawn to things as a kid or teen and not knowing they were “wrong,” like R. Crumb.

LB: To me, that worked seemed very inventive and like such good ideas. You could see that people had so much fun making them. You could feel the joy, even in the horrible things. I’m sure the message still infiltrated and did some damage, but that energy was important to me.

EW: Fun and joy really comes through in your work. You seem to mash together paintings and cartoons, humor and the grotesque. How do you balance it all, or does it just come naturally?

LB: It does, but it helps that I didn’t go to art school or learn the “rules” of painting. I didn’t have parents who ever said, “No, you can’t do this” or “No, that’s not how you do that.” I never even once heard my mother complain that anyone was fat or ugly. We went to nudist camps every summer. I didn’t grow up with any sense of what I was “supposed” to do. That means I have technical problems—I was repainting stuff this morning!—but I don’t feel the weight of art history judging me. Instead I just start with a feeling, which means there are probably 10 paintings behind the final one. I have to make the painting to see that I don’t like it, then I build from there. I’ll make a sketch, mostly to see the proportions, but it almost never really ends up like the sketch.

EW: What are you showing in the SITE Santa Fe International in June?

LB: D.H. Lawrence [novelist who figures as a “person of interest” in the exhibition, which is structured like a story] made erotic drawings that will be included. They were banned in England! I am making some small paintings to go with those. While making those, I re-read Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1926) and realized how afflicted he was by the feeling of not being in your body. The British were so anti-feeling-things.

EW: Which gets us back to the British spies you mentioned earlier. A lot of the skepticism toward figuration has to do with voyeurism—and for good reason. But your work reminds us that spying isn’t always bad: the British were trying to stop the Nazis, after all.

LB: Yes, and it’s important to me that I am never making fun of the figures I am painting. I want to spy on them, but I’m thinking about them, not who’s going to see them and what they will think.