Obedience on a Plate: A Look at Designing the Gesture of Power

Walking into Designing the Gesture of Power doesn’t feel like entering a typical gallery. It’s quieter than you expect — not in volume, but in tone. Nothing shouts. There are no flashing signs or didactic panels commanding your attention. Instead, there’s a kind of poised restraint — surfaces gleaming, objects placed with an almost eerie exactness. Curated by Purva Kundaje, the space is laid out with surgical precision, more like a laboratory than a lounge. At first, it feels familiar, domestic even. But that comfort doesn’t last long. The deeper you move into the overall space, the more your body begins to notice itself—like a specimen under observation. You become hyper-aware of how you’re standing. How you’re holding your arms. Whether your hands are doing the “right” thing.

There’s a controlled choreography at work here — not one you perform, but one you recall. From childhood maybe, or dinner tables where the rules weren’t written but always enforced. That’s the uncanny current running beneath everything: gestures you didn’t realize you learned, now mirrored back at you through steel and form.

One of the first works that lingered with me didn’t shout for attention — it just sat there, composed and clinical. A stainless-steel surface held pieces of raw meat and fruit, positioned with a precision that made them feel less like food and more like offerings. Or evidence. The materials are fleshy, bright, and oddly static. You expect them to feel organic, but instead, they register as inert, frozen mid-gesture. There’s no rot, no mess — only containment. You realise this isn’t a still life; it’s a freeze-frame of ritual. And in that pause, something disquieting begins to take root.

Elsewhere, hands are the main actors — or perhaps the subjects. In a triptych of photographs, a series of hand positions unfold with quiet intensity. At first glance, it seems almost instructional: how to hold, how to receive, how to behave. The lighting is soft, the images muted, but there’s a tension lurking in the grips, the finger placements. You begin to recognise the script. Not written, but rehearsed in dinner manners, in etiquette lessons, in the way you were told to pass the salt without reaching across the table. What’s unsettling isn’t that these poses are unfamiliar — it’s that they’re too familiar. You’ve done this before. You still do.

The materials across the show share a certain sheen — polished metal, tight compositions, clean lines. There’s a sterility that recalls design studios or surgical theatres, and yet these are spaces of intimacy: kitchens, dining rooms, the quiet rituals of domestic life. Kundaje’s architectural training comes through here — not just in structure, but in how the body is positioned in relation to objects. Everything seems designed to be touched, but hesitantly. The way a scalpel invites the hand, but with a warning.

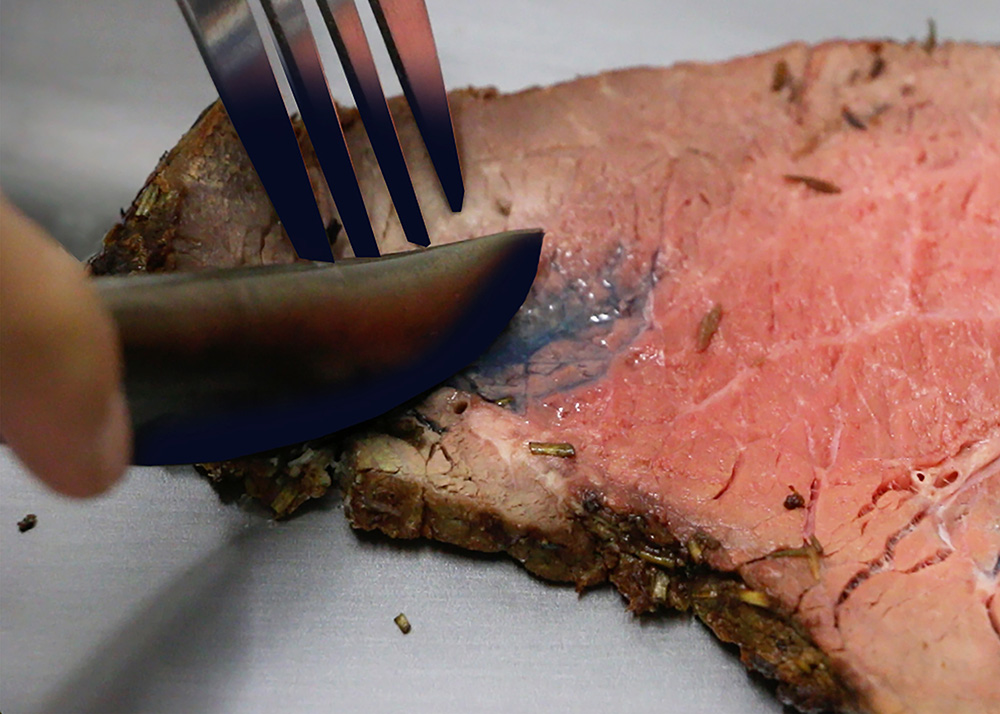

It was a small gesture that stayed with me the longest. A cold-handled knife resting against a slice of meat — not cutting, just touching. From the point of contact, a slow seep of pigment blooms outward, like a wound that has decided not to close. It’s restrained and almost tender, but also heavy with implication. Violence here isn’t loud or bloody. It’s slow, polite, and entirely procedural. You begin to think: maybe that’s what makes it so effective.

What Kundaje manages is a kind of whispered authority — the kind that governs not with commands but with calibration. A slight change in weight. A curvature that suggests, not enforces. It’s a choreography you’ve absorbed without realizing. You follow without protest because it never asked you outright.

By the end, you’re not just observing these pieces. You’re implicated in them. You leave the space not disturbed, exactly, but more alert. To posture. To muscle memory. To the quiet power of objects that claim to be neutral. And when you sit down to dinner next, fork in hand, you might find yourself pausing — not out of doubt, but out of recognition.

The post Obedience on a Plate: A Look at Designing the Gesture of Power appeared first on Our Culture.