The Enduring Legacy of ’80s Harlem Drag Balls

This article is part of Hyperallergic’s 2025 Pride Month series, spotlighting moments from New York’s LGBTQ+ art history throughout June.

It’s been nearly 34 years since Pepper LaBeija walked across the screen for a global audience in the opening of Jennie Livingston’s seminal documentary Paris Is Burning (1990). Rare glimpses into New York City’s Black and Latine drag balls of the ’80s were shown to a global audience by way of the widely celebrated and critiqued film.

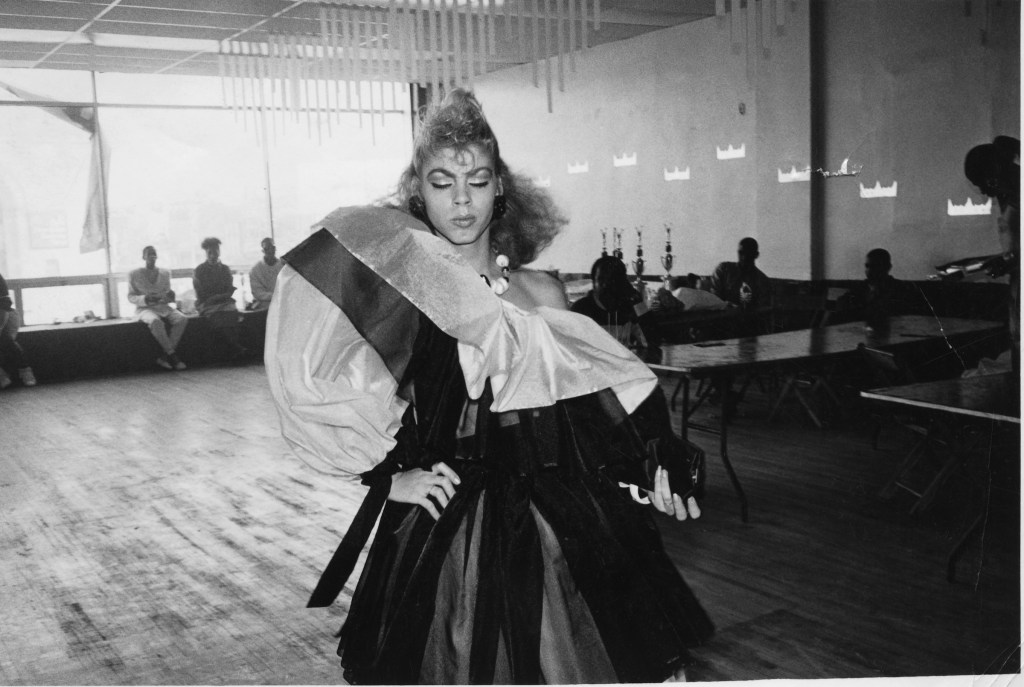

Minutes into the film, Pepper LaBeija, “mother” of the Royal House of LaBeija, enters a red-walled multi-story venue with an Elk head tacked to the wall. A crowd cheers her on as she stuns in a lavish, overflowing golden gown, black gloves, and sunglasses. The West 129th Street venue in Harlem, once called Elks Lodge, became the Faith Mission Christian Fellowship Church in 1997, but the red doors of the congregation still nod to the iconic venue where queens competed in overnight balls for winning titles. While drag balls have not been held there for many years now, the site remains a significant landmark of LGBTQ+ history.

“Our balls are like our fantasy of being superstars,” Pepper LaBeija tells the off-screen interviewer, presumably Livingston, in Paris Is Burning. “A lot of those kids in the balls don’t have two of nothing. Some of them don’t even eat; they come to balls starving. They’re under 21; they sleep on the pier … They don’t have a home to go to.”

Livingston made the film between the mid- and late- ’80s against the backdrop of the peaking HIV/AIDS crisis, though it is seldom mentioned throughout its over 70-minute run time. Instead, interspersed interviews with ball figures, including Venus Xtravaganza, Dorian Corey, Kim Pandavis, and Octavia Saint Laurent, focus on dreams of fame and world travel, particularly to Paris. Interviewees reflect on their ball “house,” described by present-day House of LaBeija on its website as “a safe-haven for queer people of color and a home with a family for those who don’t have one.”

“We leaned toward the performative aspect and the found families. We tried to focus on how these people survived,” Livingstone said in an interview with Hyperallergic in 2019.

Elks Lodge is gone, but some of the ball houses first introduced to the masses through Livingston’s film are still around and flourishing. Today, the Royal House of LaBeija is a trademarked membership organization with chapters across the US, Europe, South America, and South Africa.

The house was founded by Crystal LaBeija, who kicked off her pageants fueled by frustration with racial bias in the broader Manhattan drag world in the ’60s and ’70s. The Royal House of LaBeija identifies itself as the first-ever ballroom house and the first to hold events that raised awareness for the HIV/AIDS crisis during the 1980s, as the Reagan administration initially ignored the epidemic.

Earlier this year, the Royal House of LaBeija unveiled a bust commemorating Crystal LaBeija at the Museum of the City of New York, which is hosting the exhibition Urban Stomp: Dreams & Defiance on the Dance Floor through next February.

Jeffrey “Kiddie Liddah” LaBeija, the house’s overall overseer who has been involved in the ball scene since 1987, described the significance of the drag balls in an interview to Hyperallergic. As a gay Black person, he said, it was considered “radical to flaunt and live your life,” so balls were held overnight at event venues like Elks Lodge, where organizers leveraged relationships with promoters to gain access to space. “What caught my eye was creativity on a level I had never seen before in normal life,” Kiddie told Hyperallergic, recounting his first impressions of the New York ball scene. “I had never seen beauty on such a level, and I wanted in from the minute I went to my first ball. It was a world that I did not know existed, where we actually, for one night, lived a fantasy, and we weren’t the most hated people in the world.”

Kiddie trademarked the LaBeija name in 2023, a move he said empowered the house to tell its own story.

By the time Pepper LaBeija died in 2003, Kiddie told Hyperallergic, New York was no longer the mecca of ball culture. The culture moved south to places like Atlanta. Kiddie was enrolled at Virginia Commonwealth University when he went to see Paris Is Burning in the theater one weekend.

“I’d never seen gay Black people being celebrated like I did in Paris Is Burning,” Kiddie recalled. “I finally saw that I was not a misfit.” A monologue by ball emcee Junior LaBeija, known as “White America,” Kiddie said, was the most profound speech he had ever heard.

“We have had everything taken from us, yet we have all learned how to survive,” Junior says in his monologue examining the manifestations of white beauty standards in the ball circuit.

Paris Is Burning was not universally celebrated. It was notably critiqued by author bell hooks, who questioned whether it was exploitative. Livingston has defended their work and told Hyperallergic they attempted to be the best listener they could while producing a historically important film. Some of the film’s subjects hired lawyers to attempt to gain financial compensation as the movie rose to fame. Pepper LaBeija told the New York Times in 1993 that she felt “betrayed” by the lack of compensation. Livingston distributed $55,000 among 13 of the film’s subjects after the claims were dropped.

Luna Luis Ortiz, a ballroom photographer and activist from New York City who joined the House of Pendavis in 1988, also featured in Paris Is Burning, recalls the impact of the film.

“It exposed our underground world, and it gave some of us a career, because now people looked at it as art,” Ortiz told Hyperallergic, also acknowledging that some felt the film’s director capitalized on the community.

Ortiz said he contracted HIV when he was 14 years old, and that a main reason he picked up the camera for the first time was because he thought he wouldn’t live much longer. He started with self-portraits, documenting himself, and turned the camera outward toward his community.

“And so that’s when I started to document [the balls], not realizing that I was documenting a community,” Ortiz said. Ortiz compared his experience of discovering the ball scene to Dorothy landing in Oz in the Wizard of Oz, when the film turns to color.

“I went along and thrived and was living and surviving with HIV, and I was also experiencing this wonderful world,” Ortiz said.

In the decades since the release of Paris Is Burning, ballroom has exploded globally, Ortiz said. Though he sometimes wishes the culture was still unique to his community, he also recognizes the positive impact of its expansion.

“It’s giving people hope that they’re not alone, that they have family,” Ortiz told Hyperallergic. Kiddie described ball culture in 2025 as a sort of “artist incubator.”

“You can actually take nothing and make it something, and that’s what I did,” Kiddie said. “I, [having] no formal education, made it something, something that can be here when I’m no longer on this Earth. I’m very proud of that. I get emotional just thinking about it.”