The French Lesbian Curator and Spy Who Saved Art From the Nazis

When World War II broke out, museums across France took their most precious artworks off the walls and hid them away for safekeeping from bombing. But no one suspected the greatest threat to these treasures: the Nazis’ massive art looting scheme, wherein they sought to plunder museums to bolster the image of their own galleries, take modernist (or, in their words, “degenerate”) art down from view, and disenfranchise Jewish art collectors — while raking in money for themselves along the way. When Nazis began storing stolen pieces in the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris, none of them realized that the building’s petite, bookish curator understood German. Throughout their occupation of Paris, curator and art historian Rose Valland was taking detailed notes of their crimes, and in the process, saved scores of masterpieces that otherwise may have been lost forever.

Right: “The Raft of the Medusa” (1818–19) by Théodore Géricault about to be loaded onto a scenery truck from the Louvre in 1939 (image via Archives nationales, France, 20144792/250)

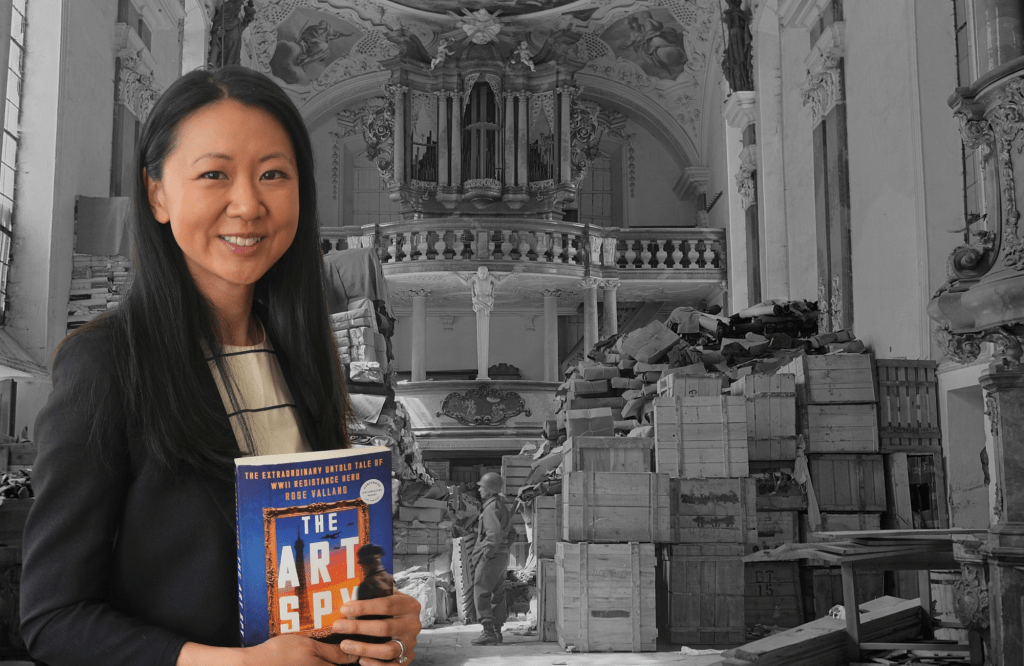

Although Valland published a popular account of her daring deeds after the war (part of which was turned into a Hollywood film), there is still so much that the world doesn’t know about this underappreciated French Resistance hero. But this month, after years spent diving into archives, uncovering long-lost journals, and even talking with Valland’s family members, author Michelle Young published stunning new revelations about this remarkable woman’s life in a new book titled The Art Spy.

In this episode of the Hyperallergic Podcast, Young joins Editor-in-Chief Hrag Vartanian to discuss the story, from the identity Valland kept quiet as a queer woman and her accounts of seeing paintings burned in the courtyard of the Jeu de Paume, which were initially met with disbelief, to her daring escape on a flatboat on the Seine.

Subscribe to Hyperallergic on Apple Podcasts and anywhere else you listen to podcasts. Watch the complete video of the conversation with images of the artworks on YouTube.

A full transcript of the interview can be found below. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Michelle Young: The Art Spy. Paris, August 19 to 20, 1944. A torrential storm was pummeling Paris, turning the skies forebodingly dark over a city in the midst of a tense mandatory blackout. The clamor of thunder and the sounds of war rose to a crescendo as the battle for Paris began. After four brutal years of German occupation, the City of Light was allegedly going to be liberated. Cannons boomed, and shells whistled above the Seine, just meters away from the Jeu de Paume museum. Inside that 19th century building, 45-year-old French art historian, Rose Valland, peered out from a slightly open window. From the Jeu de Paume, Rose could see dark smoke rising from the Grand Palais, the glorious palace of iron, steel, and glass on the Champs Élysées that was used throughout the occupation for propaganda exhibitions.

The Germans had sent a remote control tank barreling into the building to kill the French resistance fighters who had barricaded themselves inside. At just under 5 1/2 feet tall, Rose was dwarfed by the scale of the Jeu de Paume’s colossal arched windows, but there was nothing timid about her. Four years earlier, the Nazis had seized the museum to make it a headquarters for its art-looting force to process the Jewish-owned art they had begun to plunder en masse in France. Her boss, Jacques Jaujard, the director of the Musée Nationaux — the French National Museums — immediately ordered her to “remain at all costs at the Jeu de Paume Museum” and covertly spy on the Germans. Iron-willed Rose was determined to see her orders through, but she did not know that she would risk her life for the next four years to achieve her mission.

Hrag Vartanian: Hi, and welcome back to the Hyperallergic Podcast. When they were in power, the Nazis looted hundreds of thousands of artworks. They stole from state museums as well as private collections, particularly those of Jewish art collectors, both to hide from view modern works they saw as “degenerate” and to bolster the image of Nazi museums. And of course, to make money. One of the places they stored a lot of their stolen art was at the Jeu de Paume. When they took control of the museum, they didn’t think much of the curator in charge. The quiet and unassuming Rose Valland didn’t tell them that she also understood German, and she quickly figured out their plans for the art. No one suspected that she was secretly recording all the details of the looting and keeping meticulous notes on exactly where each piece was being taken.

When the war was over, she passed this information along to the famed Monuments Men. Those are the guys who worked to track down the treasures that the Nazis stole. In the process, she saved works by every major modern artist from Cézanne to Picasso. And after the war, she published a popular book and part of her story was even made into a Hollywood film. But there’s still so much the world doesn’t know about this remarkable woman.

So today, we’re talking to Michelle Young about her new book, The Art Spy, where she uncovered a whole new fascinating side of the curator and French resistance spy, from the parts of her life that she kept quiet, including her own identity as a queer woman, to the museum leaders that chose to collaborate with the Nazis. I’m Hrag Vartanian, the Editor-in-Chief and Co-founder of Hyperallergic. Let’s get started.

Hrag Vartanian: So today, we have Michelle Young to talk about her new book, The Art Spy. Hi Michelle.

Michelle Young: Hi.

Hrag Vartanian: So this is very exciting. You’ve been working on this for a while, and it seems to be a labor of love. Would you characterize it that way?

Michelle Young: Yeah, it’s been about four years now.

Hrag Vartanian: So Rose Valland. That’s the person at the core of this book, and it’s amazing how many people don’t really know who she is.

Michelle Young: Yeah, that’s what got me started.

Hrag Vartanian: I know, but it’s an incredible story. I mean, here’s this lesbian art historian curator working at a museum in Paris at the beginning of World War II. Why don’t you introduce her a little bit to us, because Rose is quite a character.

Michelle Young: Yeah. So you got her started. But Rose Valland is an art historian spy who basically helps take down Hermann Göring and his art looting ring during World War II and continues to fight for justice after the war. But my book focuses on her wartime darings.

Hrag Vartanian: I mean, it’s an incredible story. But before we get into more details, let’s talk about you a little bit.

Michelle Young: All right.

Hrag Vartanian: I would love to hear “the Michelle story.” How did you get involved in art? Where did you grow up?

Michelle Young: I grew up on Long Island. I’m from a town called Setauket. It is where America’s first spy ring actually started.

Hrag Vartanian: No way!

Michelle Young: George Washington created a spy ring based on members all from that town. So maybe that’s where my obsession with spies comes from. My parents are from Taiwan and they’ve always been very interested in art and culture. So growing up I would be dragged to museums in whatever city we were visiting, probably starting at 8:00 a.m. And I studied art history in college. I originally thought I was going to be an iBanker. That did not really pan out well.

[Both laugh]

So I switched majors a year in at Harvard and studied art history. Then I got a little derailed and went to work in the fashion industry as a merchandiser for several years, and then kind of freaked out in my mid 20s and looked around my apartment and it was full of books about art and architecture.

Hrag Vartanian: Couldn’t give it up, right?

Michelle Young: Yeah. I remembered again what it was that I loved.

Hrag Vartanian: What iBanking didn’t suck that interest out of you? No?

Michelle Young: I actually never even got started iBanking. So that’s good news.

Hrag Vartanian: That is good news. Good news for the art world and the literary world too. So then, how would you describe your journey to make this book?

Michelle Young: So for many years I was running a company called Untapped New York, which still exists.

Hrag Vartanian: Absolutely, and it’s fantastic. Everyone should check it out.

Michelle Young: And part of what we do are these experiences and tours, and we used to host drinks after certain tours. And I met a narrative nonfiction writer named Laurie Gwen Shapiro. And I think from that moment she said, “You should write a book.” And I said, “I don’t really have a story, so I’ll let you know. You’ll be the first to know.” And over the years, I sent her some ideas. She usually told me they were terrible. And one spring I sent her this idea because I had discovered her in a book that I had been reading called Göring’s Man in Paris by Jonathan Petropoulos. And she said, “This is the story.” And she really helped me actually sell this book and prepare to write it.

Hrag Vartanian: That’s amazing. So tell me a little bit about Untapped New York a little bit, because I mean, that’s how I first got to know you.

Michelle Young: Yeah, I know. Our publications are roughly the same age as well.

Hrag Vartanian: They are, which is kind of surreal, right?

Michelle Young: And not many of them that were created around that time are left. And we’re still here.

Hrag Vartanian: I know. That’s so true. Why did you start Untapped?

Michelle Young: I quit fashion and I started wandering around New York almost like a tourist. So I felt like I knew New York, but turns out I didn’t. And when I put a new way of looking at the city that I lived in, there was so much to discover. And so that was the real origin behind it. It was not to have a company or to make money, it was just, “Let’s discover. Let’s share this information with the world.” These days, we’re mostly an experienced company, but we keep the editorial around because it’s my first love.

Hrag Vartanian: Of course.

Michelle Young: So we’re still sharing New York City secrets.

Hrag Vartanian: So now, what do you feel like you learned from Untapped that you’re bringing forward? What were some of those key lessons?

Michelle Young: Well, I think when I research, whether it’s for an article that I’m writing for Hyperallergic, Untapped New York, or the book, I’m looking for that source that no one has looked at either ever or in a long time. So in the early days, I would always check Google Books, because there’d be some obscure journal with some fact that transformed your story. You entered with that piece of information instead of what everyone else is saying. And of course, in recent years, it’s become a PR machine. So basically you’re fed the information and they’re expected to write a very standard story. So, how do you enter a topic through a different way?

Hrag Vartanian: Absolutely. Which I guess comes to this. So how did you enter this topic in a different way?

Michelle Young: So I wanted to look just at five years of her life. That was important to me.

Hrag Vartanian: Yes.

Michelle Young: It’s not a biography, it’s an action oriented but true story of this woman. And I felt like she had not gotten her due. Her story is actually, I think, extremely exciting. But she’s always positioned as, “Here’s this mousy art historian who worked in this museum.” No, no, no. She’s someone who worked under the nose of the Nazis for four years every day. Survived, lived to tell the tale, and has really dramatic stories within that. So I felt that my job as her newest biographer is to make her life exciting.

Michelle Young: Rose had a reputation for being overly serious and too blunt for her own good, but her unflappability had proven useful in the war. She had learned to play the role of a nobody to the Nazis. Not important enough to notice, not congenial enough to be flirted with, and too grave to be easily friends with. Unlike the other women who worked in the French museums, she didn’t bother much with her looks. Her most defining accessory was her round spectacles, which gave her an air of erudition. Although it was in vogue to wear one’s tresses in soft waves just above the shoulder, Rose simply brushed her brunette locks to the side and pulled them back in a neat bun. She left her eyebrows natural and mildly unkempt unlike those popularized by cinema stars like Arletty and Danielle Darrieux, who wore them razor thin and drawn in darkly with pencil.

Sartorially, Rose did her best to fit in. Though she would have much preferred to wear pants, she donned feminine ankle-length dresses and blended in with the rest of the women in Paris. Modest, traditional, and discreet. Still, the Germans had accused Rose of everything in their arsenal: sabotage, theft, and signaling to the enemy. They subjected her to invasive interrogations and searches and even expelled her from the museum on several occasions. But she talked her way back in every time, explaining calmly that she was just a lowly employee of the French National Museums who oversaw the building’s maintenance and the remaining art collection. In reality, she was one of the most well-educated art historians in France, and nearly every one of the German accusations had been true.

Hrag Vartanian: First of all, I just want to say how well-written the book is.

Michelle Young: Oh, thank you.

Hrag Vartanian: I mean, I just think it’s really a page-turner, and I will say, as I told you before, but I’ll tell everyone else, I loved it so much that I was like, “No, I’m keeping this for my vacation in June.” So I didn’t finish it on purpose. I was like, “I want to be able to enjoy this.” Because it goes into these deep histories of all these different people.

So we’re talking 1939 to ’44, and that’s this very small period, which I have to say, when you first told me about the book, I was like, “But there’s been so much written about those four or five years, right? How are you going to say something new?” But you’re able to do it. So how did you do that?

Michelle Young: I think I thought of it as almost like a movie. And I thought of it from the perspective of the reader. And I wrote this book with no outline. At the end of every section or every chapter, I would think, “Where should it go next? As the reader, who do I feel like I need to visit again?” And I think that was really the framework of how I put together this thing. And then I also discovered the story as I went along, like a reader discovers it. And hopefully, I think that’s a kind of unique way to write such a large book. And that really comes from my architecture background, which really taught me, “You’ve got to iterate and iterate, fail, try again, and then something is created out of this process.”

Hrag Vartanian: Absolutely. I feel that.

Michelle Young: But also to your question, there is the idea of looking at the war from the art perspective that I think is not fully tapped at all. And there are many ways to talk about it. And here we talk about not just the looting of art by the Nazis, but how do these countries and museums protect for war and then how do they survive under the occupation.

Hrag Vartanian: Yeah. And there were so many lovely moments, including when you’re like, “Well, the Nazis accused her of being a spy and this and that.” And you’re like, “Mostly true, but…”

[Both laugh]

…which I love because fact that she was able to do all this, it’s actually pretty incredible.

Michelle Young: I read a lot of stories about women spies. That’s like my favorite sub-genre of books, basically. No exaggeration. And every time I read them, I think, “What would I have done? Could I have survived this?” The answer is no. And especially with her, it’s the daily stress that must have been to keep that poker face, to pretend she was not doing what she actually was doing. That question ran through my head the whole time.

Hrag Vartanian: And the other thing I was really intrigued by — and I guess I wasn’t expecting this part of the story — was how much institutionally as a woman going through French civil service there were these barriers. I loved reading that because it’s so lost to us in a contemporary moment. What did it tell you about being a woman in 1920s, ’30s, ’40s France?

Michelle Young: It was almost like women working was a curiosity.

Hrag Vartanian: Right?

Michelle Young: Yeah. And therefore, they were almost never paid. And they assumed you had some man to support you. And so one of the only other — maybe the only other — female curator, she was the wife of a famous sculptor, George Saupique, so she didn’t need to be paid, because here’s George Saupique!

So women had a really hard time, and especially someone like Rose who didn’t come from Paris, didn’t come from a wealthy or institutionalized successful family and was trying to make her way.

Hrag Vartanian: So what did you learn about Rose? What was it for you? First of all, what was it about her personality? I mean, other than being a spy, clearly that’s your soft spot that may have spoken to you. What was it about her? Because when you take on a project like this, you’re having a conversation with the deceased a little bit.

Michelle Young: Yeah, I think it was two things. One, her persistence really felt something that I identified with. In terms of writing this book, getting the information that I needed to tell any particular scene was a vast project in itself. And I’m someone that never gives up until I’ve exhausted all the avenues of possibilities. And even if I don’t find it at that time, it’s in the back of my mind. And so there were things that I tabled thinking hopefully I’ll come across it in some random way.

Hrag Vartanian: I love that.

Michelle Young: That was a big one. I think this idea that as a woman, as a lesbian, she was constantly being underestimated. And I feel like in the early parts of my career—

Hrag Vartanian: As a working class person too in background. Absolutely.

Michelle Young: So as a person of color in America, and especially as a petite Asian female, you get a label put on you. And I had to find my own way to work my career because of that. I worked in the corporate world before, but everyone just assumes things. And so I realized early on in my mid 20s, I’ve got to start my own thing. And through that, then my career can grow.

Hrag Vartanian: So now, what was the craziest fact you discovered about Rose if you want to share that for people, to whet their appetites?

Michelle Young:

One of the things that I worked on for a long time was she had witnessed this burning of 500 paintings. Modern paintings, Picasso, Léger, these types of painters. Things worth millions and millions today. She claimed that she had seen it. The Nazis burned them in the garden of her museum in the summer of 1943. And it was something that had been questioned immediately after she wrote this in her book. But I traced it back, and it was the Nazis in the museum who made a statement that said, “It didn’t happen! And if it did, Rose was involved.”

But once something is questioned, it starts to enter the public record, and it gets repeated and repeated. So with myths like that, you have to start digging into the root of it and then try to find the evidence around it. So I’m excited to say that I’m able to prove incontrovertibly that this event happened and that she was correct.

Hrag Vartanian: It did happen.

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: Hundreds of paintings.

Michelle Young: Yeah, she says about 500 modern paintings were burned.

Hrag Vartanian: Unbelievable. Right?

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: But it’s so interesting. And I think that’s one of the things about this book that I think is important is because you can see contemporary parallels. And I think in that case, that’s very “fake news.” As soon as someone makes an accusation, you accuse the opposite. And we can all interpret that the way we want to. But that’s pretty shocking. Right?

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: And then the other part is when the ideology of the Nazis were being disseminated to museums, how many museum directors just complied?

Michelle Young: Yeah. And I give that example of one of the most important art historians and curators in Germany, at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meiste…

Hrag Vartanian: The Picture Gallery?

Michelle Young: The Picture Gallery. Yes, exactly. He immediately capitulated, and even tried to fudge his records a bit to say, “No, we bought it with public funds, so it wasn’t me.” But yes, you use the public funds.

Hrag Vartanian: Right. And “most of them were donated.”

Michelle Young: “Most of them were donated.”

Hrag Vartanian: I think that was part of it too.

Michelle Young: Exactly. And he managed to survive all the way to the extent of becoming Hitler’s curator for the Führermuseum, his pinnacle art project.

Hrag Vartanian: Unbelievable, right? Which just shows how those who comply kind of fudge the system.

Michelle Young: Yeah. So there were echoes throughout. And when I was really deeply embedded, I was basically living in 1930s, 1940s Nazi Europe. And I would see and hear similar phrases being thrown around here and then read it in my paper. So that was kind of harrowing.

Hrag Vartanian: Yeah, I bet. So how was that experience? Because heard from historians, especially of genocide where they say they end up having slight PTSD symptoms or they have these nightmares of research material. Did any of that happen to you? This is pretty harrowing material.

Michelle Young: Yeah. I don’t think I had nightmares, but early on I was reading Mein Kampf in the middle of the night, and that was really creepy. I had a newborn. I was pumping, and then I was reading Mein Kampf.

Hrag Vartanian: I mean, I’m sure you creeped yourself out sometimes.

Michelle Young: Oh, yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: Where you’re like, “Oh, and here we are again.”

Michelle Young: Yes, yes.

Hrag Vartanian: Were any real challenges or obstacles in the research you were doing?

Michelle Young: Yeah. Rose was not someone that shared a lot of information. Definitely almost never any emotions. And even in her memoir, some of the most exciting chapters, she actually cut out or the editor cut out. So there’s a chapter about her escape from Paris with all the museum guards on a flat bottom boat through the Seine. So exciting. And I managed to find the chapter that was cut in an archive.

Hrag Vartanian: Amazing. Was it really juicy?

Michelle Young: Yes. And I had to scour her hand scribbled notes within the documents in the archives to try to find and figure out what her true personality is, not the one that she presented out in the world, in her very academic book about the war.

Hrag Vartanian: I love that. And I did love the way the photos were interspersed throughout the book.

Michelle Young: Yeah. That’s a new way to arrange things, I feel like, in books. It used to be a center section, but now you see things as you’re reading them, which is nice.

Hrag Vartanian: Absolutely. And I feel it really captures a little bit of that energy, that image of…

Michelle Young: Oh, the “Raft of the Medusa!”

Hrag Vartanian: It’s like being pulled out of the museum like that. Wow.

Michelle Young: Actually, yeah. So that’s part of the story about Rose helping to protect the art in the French museums during this time. This was one of those paintings that was so big, they had to get a theatrical trailer to move it.

Hrag Vartanian: It just kills me that it’s uncovered.

Michelle Young: Oh, yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: The way it’s being moved, it looks fully uncovered.

Michelle Young: A lot of the art was stored this way actually.

Hrag Vartanian: Isn’t that crazy?

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: You’re driving through the streets of Paris with an uncovered “Raft of the Medusa?”

Michelle Young: And actually, it has a dramatic incident where probably it should have been covered.

Hrag Vartanian: Really?

Michelle Young: Yeah, they hit some electrical wires.

Hrag Vartanian: Oh, right.

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: There we are. See? Always a little bit of drama in the art world.

So now, what did you understand about Rose in general? Because she seemed like a very private person, which I assume most queer people in that era would have to have been. You mentioned the dangers of that, but more than that, to deal with that kind of daily, frankly, humiliation of being looked over. You talk about how Verne, the guy at the Louvre who is constantly writing critical letters, is like, “Well, we can get someone who may be better qualified.”

Michelle Young: And you’re like…”She basically had five graduate degrees.”

Hrag Vartanian: Right, exactly. And you even say that she was actually probably better educated in the field than he was.

Michelle Young: She was for sure.

Hrag Vartanian: And then she sits there and she’s doing the daily work of being at the museum to safeguard this art.

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: Why did she feel the need to protect this stuff with that kind of vigilance?

Michelle Young: Right. So she comes from a working class family. Her father’s a blacksmith, and she discovers art at some point in her younger years. And for the rest of her life, she’s driven by this idea that there is this idea of beauty in the world that must be saved. And I thought about that a lot, in terms of, “We need to instill this in the next generation. A drive for something greater than their day-to-day, whether it’s just stuck on Instagram or whatever.” But I think now it’s more important than ever. We have to be driven by something bigger. And that was really important for me to explain. I think that’s why we need to celebrate someone like her. Because it was not about money. It was not about fame. It’s something unquantifiable.

Hrag Vartanian: But also communal.

Michelle Young: Yeah, right.

Hrag Vartanian: It wasn’t just about her.

Michelle Young: No.

Hrag Vartanian: At all.

Michelle Young: Yeah, it was about society.

Hrag Vartanian: She felt this need to preserve this thing for everyone. There’s something special there. And that’s the part that I kept going like, “Oh, I wonder what the deal was here.”

And now you’re telling me that even her biography was censored in a way or omitted certain things. Why do you think that was?

Michelle Young: She was very focused after the war to try to lay out why and how the Nazis looted art. And so it became less of a memoir and more like a thesis. And so in that light, her chapter about escape was not really relevant, and all the exciting points got minimized.

Hrag Vartanian: So it became less about her and more about this thing.

Michelle Young: Yeah. And that’s a testament to her. She did not want this to ever happen again. But I think for her own posterity, that’s how she got shortchanged. And actually, after her book was published in the early ’60s, Hollywood did option a chapter of her book and made it into the Burt Lancaster movie called The Train. And so she was well-known and she did have fame at that time, but I think the longevity of her book wasn’t there. And she claims that the French government actually censored it after.

Hrag Vartanian: Oh, really?

Michelle Young: And people prevented her from writing a sequel.

Hrag Vartanian: Why?

Michelle Young: Her work started to get a little too close to the powers that be.

Hrag Vartanian: Yikes.

Michelle Young: There were people like Henri Verne, for example, who served as middlemen to the Nazis. This is something I actually discovered in the US archives. The French don’t have a record of this.

Hrag Vartanian:You’re kidding.

Michelle Young: Yeah. The US documents had a list of Nazi middlemen, and there he was suddenly. And I was like, “I knew he was a bastard based on the stuff he wrote about her!”

Hrag Vartanian: Were there a lot of art people that were intermediaries?

Michelle Young: Yes. People were just very opportunistic at that time. There were a few people like Rose, who were so by the book and knew what the priorities were, and were looking to a day in which the Nazis would lose the war. She was thinking, “We’re going to use this evidence that I’m gathering in war tribunals and to get the art back.” So she was thinking far ahead and believing in mankind, basically.

Hrag Vartanian: I mean, that’s pretty incredible that she had the foresight to do that. That’s pretty incredible. So now let’s talk about, I can’t ask you as Untapped New York founder, not to ask about the New York part of the story.

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: Do you want to talk a little bit about those New York aspects?

Michelle Young: Yeah. So I actually have two storylines in this book. There’s Rose’s storyline, which is obviously the main one. But I wanted to tell the story of art looting in a way that the reader can grasp. It’s not just X collection and Y collection, and these are all looted and so much work is looted. I follow the story of one family, and it’s the Rosenberg family. Paul Rosenberg, the patriarch is the exclusive art dealer to Picasso, Matisse, Léger, and Braque.

Hrag Vartanian: So an important person.

Michelle Young: Exactly. And their story is amazing. Part of the family makes it to New York, escaping through their own harrowing journey. And the son, Alexander Rosenberg ends up fighting for Charles de Gaulle as part of the Free French. And miraculously, his story and Rose’s story intersect in the last section of the book, which is another reason to bring their storyline in. So in terms of New York, Paul Rosenberg ends up opening a gallery on 57th Street down the street from Knoedler and all those other art galleries.

Hrag Vartanian: In the gallery district of the time.

Michelle Young: And they’re heavily involved in the Free France movement here in New York. They meet Charles de Gaulle when he comes here. But there’s also one of Rose’s main supporters, advocates. His name is James Rorimer and he’s the director of the Met Museum. And he also actually was the person who made The Met Cloisters come to life.

Hrag Vartanian: That’s great. And then also you talk about her relationship with MoMA and working with Alfred Barr and working on these different exhibitions during her early years at the Jeu de Paume.

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: So that was actually really interesting. I guess I didn’t really know that part.

Michelle Young:

Yeah. And that was actually something I discovered too. Because what had been said before was that she was working as maybe they say unofficial curator at the Jeu de Paume. But what was her role exactly? And by going through all the papers, you realize that she was writing letters directly to Barr. She was really almost running the show because her boss, Andre Dézarrois, was traveling all around the world. I saw a quote somewhere saying like, “Befitting of his social class and station, his job was not to do the itty bitty work of the museum, but was to go and hobnob, acquire new works, plan new exhibitions,” and then it was Rose’s job to make those exhibitions come to life.

Hrag Vartanian: But she was only called a “secretary.”

Michelle Young: Yeah, for at least the first four years, she was an unpaid secretary, and then she became a kind of unpaid, entry level curator.

Hrag Vartanian: So you mentioned that she supported herself teaching classes and teaching English?

Michelle Young: She was what I would call in modern day words, hustling.

Hrag Vartanian: She really was. I was like, “Has this not ended?” Because I felt like how familiar that is now, right?

Michelle Young: Yes.

Hrag Vartanian: How many art people do I know who have these sort of passion projects? And in this case, the Jeu de Paume shouldn’t have been a passion project, but ended up becoming one. Though if you’re a curatorial assistant at MoMA, it’s sort of the same thing with the amount they’re paying nowadays.

Michelle Young: Yeah. So she’s teaching art. She is giving tours of not just her museum, but other museums. She’s teaching French. Oh, and she’s also selling art. I found all these documents about her basically acting as an art broker.

Hrag Vartanian: What was she selling? You mentioned there were a couple of paintings she sold to large museums. Who was it?

Michelle Young: She sold one to the Guggenheim.

Hrag Vartanian: That was it. That was the one you were saying.

Michelle Young: So yeah. There was a Juan Gris painting. There’s another painting that’s in the Cleveland Museum of Art. And she’s listed in the provenance of these paintings, which is amazing.

Hrag Vartanian: That is amazing. I mean, she was everywhere.

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: How do you think she got through it? Because she doesn’t come from means. That must’ve been a struggle, a daily struggle for her. For her partner and her. They live together in Paris, which of course, as you mentioned in the ’20s would’ve been the hotbed of lesbian communities. But at the same time, it must’ve been hard.

Michelle Young: Yeah. She really learned to subsume her emotions. And I think she had done this at an early age since she was in the closet as a lesbian. She was an outsider in all the schools she ended up going to. And the thing that really struck me was there was an interview in Elle magazine, probably around the time the movie The Train came out. And at the end she’s back in the museum, they’ve turned into the set for the movies, and there’s Nazis running around in their boots with their rifles. And she actually has a moment where she loses her composure and cries and she runs out of the museum. And then I think it’s the next day, or whenever they interview her again, she’s like, “I don’t know what happened.” But basically all the years, even after the war, she never addressed any of this stuff, it actually came to the surface suddenly when she was back in that environment.

Hrag Vartanian: Unbelievable.

Michelle Young: But I think when you have a history of learning how to hide who your true self is…that’s what made her a good spy. She just had to continue doing it in a slightly different way.

Hrag Vartanian: She knew her code-switching.

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: She knew it well, right? She really did.

So now, what do you think people are going to be most surprised about in this story? I mean, we’ve heard stories of the resistance. We’ve heard about stories about the different people who’ve saved art through the years, the George Clooney film and all. For me, I loved hearing just about her story, of this working-class woman who moved to Paris and tried to make it. But as you even mentioned, with all her education, she never quite had that ease in elite society.

Michelle Young: Right.

Hrag Vartanian: There was always something. How about some of the people that knew her that you interviewed or her family and these types of things? Tell us a little bit about what they knew about her.

Michelle Young: Overall, everyone said that she was a very tough person. And there were people that ended up working on the Rose Valland Association in France, but they actually didn’t even like her.

Hrag Vartanian: [Laughs] What?

Michelle Young: There was a woman, she lived in her hometown, who was married to a famous actor in France. And she was passionate about this organization that they had created in the town to have her memory. And I was supposed to interview her, and she unfortunately died around the time that I was supposed to interview her. But from what I heard, she didn’t like her as a person. But I think it’s such a testament to Rose and what she did, that even if you didn’t like her, you believed that what she did was important, and you wanted to help her fight for that and for posterity to know and future generations to know.

I think maybe the most surprising thing for most people is how extensive the protection of art was in France. This wasn’t just packing up some artwork. They planned for eight years, I think, for a future war. And it was a well-oiled machine by the time war broke out. So the amount of resources dedicated to making sure that the art was protected is huge. And I had written a story a few years ago about Ukraine and how it reacted to the Russian invasion. And they were not prepared in nearly the same way.

Hrag Vartanian: No. And you mentioned that it was partly because of World War I.

Michelle Young: Yes.

Hrag Vartanian: Because they actually had that experience of that it was only when the Germans crossed the border did they come up with a plan to save the art.

Michelle Young: Right. And they were like, “We can’t ever have that happen ever again.”

Hrag Vartanian: Right.

Michelle Young: I think the other thing is a lot of people assume they moved the art because they thought the Nazis would steal it. They actually had very little conception that that was going to happen. It was to protect it from bombings and military action. And then later it became also convenient that they had been moved out of Paris.

Hrag Vartanian: Right. You mentioned also even the things they kept, they filled the galleries with sandbags and locked things and different…

Michelle Young: A lot of on-site protection, because they couldn’t move everything.

Hrag Vartanian: Right.

Michelle Young: The other-

Hrag Vartanian: It showed me it was about bombing. That was really their top concern.

Michelle Young: Yes. And they ended up moving, for example, the Victory of Samothrace.

Hrag Vartanian: Yeah.

Michelle Young: That massive beautiful sculpture in the Louvre. They moved it at the last minute because they actually thought that it would survive in the place that it was at. But they realized that the vaulting above would actually collapse. They did a new engineering study and they’re like, “Oh, no.” So it got moved out the day that a war broke out.

Hrag Vartanian: That’s crazy.

Michelle Young: I think the other surprising thing was that Rose’s partner is actually arrested and interned by the Germans. They were arresting everyone British because they were considered enemy aliens, the Germans thought they were.

Hrag Vartanian: Even though her dad was German.

Michelle Young: Her dad was German. She had gone to school in Germany.

Hrag Vartanian: She spoke German.

Michelle Young: Yeah. It didn’t matter. I had not even heard about this chapter of the war. And I read a lot of books about World War II. And so I think it has echoes to today because should we break out into war in America or any other western country, who is going to be considered an enemy, an “alien?” We already have this term. And so men, women and children, and elderly were incarcerated and thrown into prisons in France. And many, many died during the war, just for being British.

Hrag Vartanian: It’s so shocking, isn’t it? It fascinates me that the preservation of art like this…what do you think we can learn from it? What can we learn from these stories? What is it to preserve art? What do you think that Rose can teach us through the years about what the value of this is?

Michelle Young: I think it’s that we should not be complacent about any kind of status quo. They were always rethinking, making new lists. What should be protected? How should we do it? They lived in a time in which war could break out at any time. And I feel like we’ve gotten into a place where we just assume nothing will happen. We think everything will stay the same. But that is a false sense of complacency. And also we need to think about climate change and where are these museums located. I don’t think that many museums have planned for natural disasters. The only thing that comes to the top of my head right now is when they built the new Whitney, they made that ground floor floodable in reaction to that. But that’s kind of a rare case.

Hrag Vartanian: Right. I do think that’s starting to happen in some places.

Michelle Young: Yes.

Hrag Vartanian: Buildings in New York now often put their electrical rooms on third or fourth floors, and these are in response to Sandy and all these different kinds of incidents. I totally get that. And we just see it even in Sudan recently where the museum was looted. We may talk about the Louvre, but the reality is so many smaller museums are being impacted so severely.

Michelle Young: Every museum needs a plan. Every institution needs a plan, not just our largest ones.

Hrag Vartanian: So did it make you love art more, writing this book? What is your relationship with art after writing this book?

Michelle Young: What was interesting to me was that I thought when I started the book that I would write a lot more about all the individual paintings, but in the end, actually, it was about something bigger. And so I did talk about the paintings and some of them get a little more airtime than the others. Like, Vermeer’s “The Astronomer” was like number one for the Nazis to get their hands on. And they did get it. It’s card number one in the Nazi files.

Hrag Vartanian: Did they explain why?

Michelle Young: Well, predominantly it’s because Hitler only wanted the old masters, so that was sort of in the right vein, but it was also from the Rothschild family. And this painting had been in their collection for maybe hundreds of years.

Hrag Vartanian: I see.

Michelle Young: And so it had never been owned by anyone else.

Hrag Vartanian: So there’s a symbolism there too.

Michelle Young: Yeah.

Hrag Vartanian: Wow. Now, how about your writing? How did you feel like your writing changed or was it a challenge to you to change your writing? Or how did you challenge yourself literary wise?

Michelle Young: So I think my experience writing online was really helpful because I think when you write online, you need to hook the reader in very quickly. It’s not like sitting and reading a magazine at home or something. If you lose them in the first paragraph, you’ve lost them.

Hrag Vartanian: That’s right. They’re not coming back.

Michelle Young: So I knew how to already move between more academic writing and a more popular style. I thought of a lot of my early love, which was fiction. I only became a non-fiction person in my mid 20s or 30s. So I was thinking about the books that I loved, and how things are described, and forgetting some of the nonfiction writing that I’ve been doing.

Hrag Vartanian: Right. I get that.

So this is awesome. I think people should run out to read it.

Michelle Young: Thank you.

Hrag Vartanian: I think it’s really important. I also love that it just feels very accessible. You did your utmost to make it as accessible as possible. I didn’t feel like sometimes I’m reading these books and you’re like, “What is that? I’ll have to go look it up.” But I feel like you were very explanatory. It was very clear what was going on. And if you had just a basic knowledge of art, that’s all you needed.

Michelle Young: That was purposeful because I think the morals and the takeaways from the book are more important than being highfalutin about art specifically. And in order to do that, I really thought about, “Does this word, or this sentence really need to be on the page?” And if it doesn’t, then it’s gone.

Hrag Vartanian: That’s right. Well, thank you, Michelle.

Michelle Young: Thank you.

Hrag Vartanian: This is wonderful. And people I hope will run out and grab it. And it is quite a page turner and a great summer read. So thank you so much for putting this together and for breathing some life into Rose again, so we can all learn about her example. And I think a lot of people who work in the art world will really appreciate the struggle she went to. Because I think sometimes we have a tendency to maybe whitewash the past in terms with our imagination, where things were easier and maybe people got jobs easily or whatever. But she’s a good example of actually, it was always very tough for a lot of people in the art world, particularly when they don’t adhere to a certain kind of elite lineage and family and all that. And she proves how the art world has always been a conglomeration of a lot of different people who just love art. Including yourself.

Michelle Young: Right, exactly.

Hrag Vartanian: Well, thanks so much.

Michelle Young: Thank you.

Hrag Vartanian: Thanks so much for listening. This episode was edited and produced by Isabella Segalovich, and this podcast is brought to you by the amazing Hyperallergic members. Thank you to all the members out there. For only $8 a month or $80 a year, you too can become a supporter of the best independent arts journalism out there. We tell the stories no one else is telling. Visit hyperallergic.com to learn more.

I’m Hrag Vartanian the Editor-in-Chief and Co-founder of Hyperallergic. Thanks for listening. See you next time.