The Kooks Go Back to the Beginning

Hugh Harris says that we’re nostalgia hunters.

When he says “we,” it’s not clear whether he’s talking about himself and his Kooks bandmate, Luke Pritchard, or “we” as in all of us.

More from Spin:

- Gorillaz Construct ‘House Of Kong’ For London Exhibit

- Chuck D Is Calling You Out

- New Book on Bob Dylan Explores the Artist’s Most Influential Period of Music

He’s right either way.

Rock ‘n roll, especially the brand of rock ‘n roll that the Kooks peddle in, is a nostalgic venture. The early 2000s’ indie rock boom, particularly in the U.K., owed quite a lot to the British Invasion in its sound and style.

But when I say that theirs is a nostalgic venture in 2025, I don’t mean that the Kooks are chasing down any heights from previous hits or trying to cling to any commercial heyday. It’s just that, in the last few decades, and in 2025 especially, rock ‘n roll is referential. It’s continually trying to dig something up: a sound, a culture, a feeling. The genre’s cyclical nature means we’re all just out in the woods hunting for nostalgia, whether we’re making it or consuming it.

The Kooks can admit this, especially as they’ve gotten older along with their fans.

“You can get buried in hunting those feelings because they represent a time when things were much simpler, and we had less responsibilities,” Harris says. “So yeah, naturally, you fall back. You create a kind of wormhole to your past, because it makes you feel good about your present.”

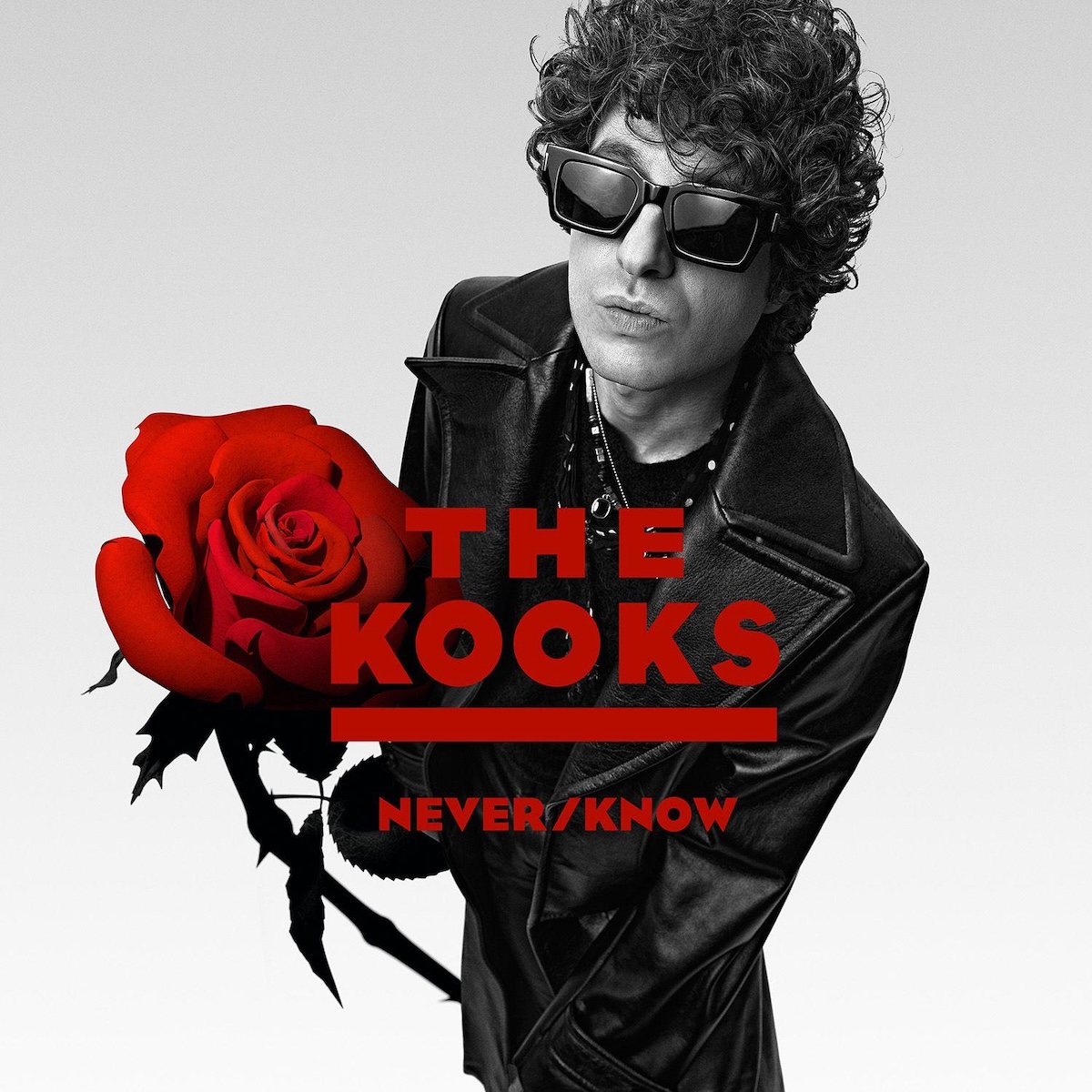

With Never/Know, their seventh studio album fully produced by the band, the Kooks have created that wormhole to the past—not just that of the rock music they love. Sonically, the music channels their influences, like early Stones, Dylan, Bowie, and the Kinks, perhaps more than their previous releases, and also burrows back to the early days of the band, where there were fewer expectations and a little more uncertainty. Now a duo, the Kooks have been on the road across their native U.K. on a stripped-down acoustic tour. Smaller venues, more intimate shows. It feels like the beginning again, and it’s provided a boost when they might’ve needed it.

“People are actually learning our songs, and it feels like a new beginning with the new music and support,” Pritchard says. “There’s a lot of love for the band still out there.”

Pritchard admits looking at the tour schedule and looking at cities and thinking, “Come on, there’s no one in Coventry that still listens to the Kooks.”

But he was wrong. “Turns out there’s a few. And that’s really nice, man, because it’s easy to take it for granted,” he says. “Bands rarely last beyond five years. We’re still here, and that’s a massive honor and testament to our fanbase.”

Stripping down everything has made them more vulnerable. There’s no hiding behind barriers or amps. It’s them in a room with their guitars and each other, come what may.

Off stage, too, the simplified touring apparatus has brought them back to the “good old days,” as partners in this dream and as friends; just a couple of guys in a splitter van, gear in the back, taking turns driving and controlling the aux cord.

The way they talk about it, it sounds a lot like the stories of married couples revitalizing their relationships after years over “their song” or reminiscing over times when the whole thing was more new and exciting; recapturing that feeling again with little things like songs they used to play in the van 20 years ago.

“Twenty years working together, we go through ups and downs,” Harris says. “But it’s a good wave at the moment. I think it’s just like capitalizing on the things that we both share in common, which are just very simple values. And realizing that, you know, the show must go on.”

They’re not the first band where things got more complicated personally as their star grew. It’s cliché at this point. But it’s an archetype, a stereotype, because it’s true. It’s real.

“I think it’s very easy to kind of lose sight of the original intention,” Harris continues, “and that seems to have been recentered really nicely.”

He’s noticed a change in Pritchard’s writing, too. Allowing himself to fall back on the things that gave him his initial spark has allowed him to write in his purest form, something that maybe he hasn’t been able to do recently due to expectations or outside influence—or any of the things that can cloud an artist’s creative vision over time.

Pritchard calls it “spooky” the way the fully formed idea for the album struck him. He saw the beginning, middle, and end all at once. He’s not sure exactly where it came from.

He theorizes that part of it came from the fact that his son has now reached the age Pritchard was when his own father passed away, so maybe he was feeling a little existential, vulnerable to an emotional breakthrough.

“I realized how much time my dad actually had with me,” he says. “It’s not that all the songs are about that or anything. It just kind of had this lightning bolt effect on me, kind of a quite joyous, euphoric feeling, and music came out of that.”

There are a few ways that aging indie rock bands can go. We’re seeing that in real time right now—sometimes gracefully, sometimes not. Pritchard and Harris are aware that they have a large fan base that has gotten older alongside them. But they’re also energized by the prospect of a younger generation finding them for the first time, just as they have for genres like shoegaze and nu metal, as rock ‘n roll’s cyclical nature continues.

“Knowing where you come from… It’s empowering,” Harris says. “As an adult moving forward with life, we need all the power we can draw from, and that’s what being in a band is about. That’s what art is for.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.