‘The Mastermind’ Presents an Art Heist That’s In on the Joke

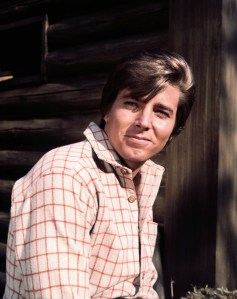

A handsome dark-haired man, his neck tucked into his shoulders, walks around a museum gallery, scanning the art on the walls. A dozing guard fails to notice just how suspiciously this man is surveying the objects on view. The man, played by Josh O’Connor, snatches a Revolutionary War carving from a window case before exiting the museum with his two sons and wife (Alana Haim). This thief is a family man, and this petty crime paves the way for a much bigger one in Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind, which had its world premier at the Cannes Film Festival last month and will be released by Mubi later this year.

What heist O’Connor’s character, a carpenter nicknamed J.B., will be the mastermind is just part of the tension that binds together this quietly suspenseful movie. For much of the film, we know very little about J.B.; figuring out who he is and what drives him, becomes almost as important as knowing if he will get away with his master plan. At times, it seems like his motivation is simply boredom.

The portrait of J.B. is revealed piecemeal, like a lens coming into focus. He seems to be an art aficionado, creating drawings based on four Arthur Dove paintings. When his accomplices start thrusting the artworks he’s been eyeing for months into the trunk of a stolen car, he orders them to be careful. He briefly displays them in his living room, taking a few seconds to observe them before storing them in a barn.

J.B.’s lack of purpose as well as his appreciation for art recall two characters from previous Reichardt movies. In Showing Up, which premiered at Cannes in 2022, Michelle Williams plays Lizzy, a sculptor and professor in Oregon who is preparing for a solo show. In Wendy and Lucy (2008), Williams is Wendy, an art school dropout strapped for cash who searches for her dog, Lucy. By contrast, J.B. appears at first to be determined and confident. He is quick on his feet and seemingly sure of himself as he plots the heist, but as the movie unfolds this facade begins to unravel.

For The Mastermind, Reichardt drew inspiration from a 1972 robbery of the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, in which two Gauguins, a Picasso, and a Rembrandt were stolen in broad daylight. The thieves were arrested and the paintings recovered days later. (The film’s fictitious Framingham Art Museum is actually the I.M. Pei–designed, red brick Cleo Rogers Memorial Library in Columbus, Indiana.) At first, a Gauguin seems like it might be the object of J.B.’s theft, but instead he goes for Dove’s Tree Forms (1932), Willow Tree (1937), Tanks & Snowbanks (1938), and Yellow Blue Green Brown (1941). Reichardt has said that the choice of Dove, an American modernist known for his abstracted landscapes, points to J.B.’s lack of ambition.

Aesthetically, the 1970s of the Worcester heist weighs heavily on the film, from the influence of Stephen Shore and William Eggleston’s color photos of America during this era to the context of the Vietnam War. Special attention is also paid to each scene’s framing. The doors and windows, whether open or closed, seem to serve as a metaphor for J.B.’s potential escape or perhaps his incarceration. He is often shown through a door or window opening, giving the impression that we are spying on or tailing J.B.

At times, The Mastermind borders on comedy. The heist itself is hilarious: a couple of amateurs with nylon stockings over their heads are caught red-handed, not by the sleeping guard, but by a young girl who pretentiously describes the art on view in French—“ennuyeux”, “dépravé”, “factice” (boring, depraved, fake). They still manage to escape, though not without delays. Later, J.B.’s father, played by Bill Camp, observes, “It is inconceivable that those abstracts paintings would be worth that much trouble.” The Mastermind is a film where mystery, humor, and art gracefully interlock.