The Pink Triangle That Mobilized a Movement

This article is part of Hyperallergic’s 2025 Pride Month series, spotlighting moments from New York’s LGBTQ+ art history throughout June.

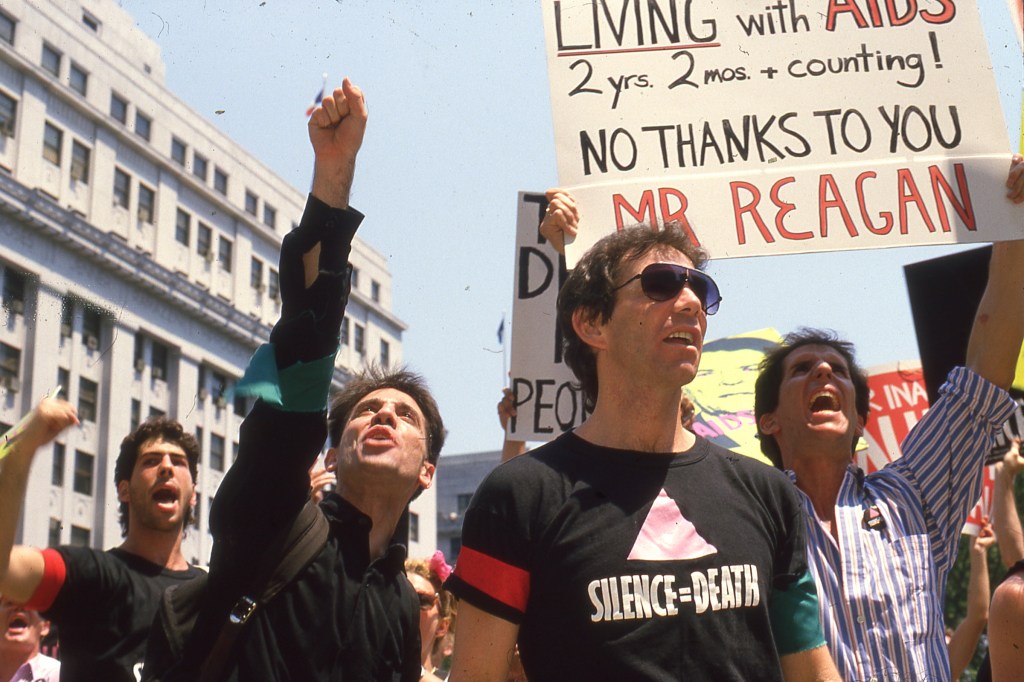

The words “SILENCE = DEATH” in bold white text against a black background, printed under a pink triangle, were what six New Yorkers had wheat-pasted between advertisements for concerts, movies, and clothing on the streets of Lower Manhattan in early 1987. In a few months, the iconic design would become synonymous with the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) — a civil disobedience group committed to ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic devastating communities across the United States throughout the 1980s and ’90s, especially affecting queer, low-income, and non-White groups.

But before the historic demonstrations on Wall Street and outside the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) headquarters; the “die-ins” at St. Patrick’s Cathedral; and the mass spreading of ashes on the manicured lawn of the White House, the searing protest imagery of SILENCE = DEATH was just crayon on notebook leaflets, drafted over the course of 1986 across a string of Manhattan apartments.

Tens of thousands of people had already died from AIDS, yet then-President Ronald Reagan had only publicly mentioned the deadly syndrome once in response to a reporter’s question. The growing painful loss, government inaction, and societal apathy brought Avram Finkelstein, Brian Howard, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff, Chris Lione, and Jorge Socarrás together as a consciousness-raising group.

“ We would meet every week at a different person’s apartment,” Finkelstein, who was also a founding member of ACT UP and the affiliated activist art collective Gran Fury, told Hyperallergic. “We would all bring food, we were assigned dishes, an appetizer or dessert or the main course, and we started out talking about what it was like to be a gay man in the age of AIDS.”

“ We would start out talking about our personal fears and anxieties, but by the end, we would end up talking about some political story that was developing,” he added.

Seeking to mobilize people after notorious conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr. proposed mandating an AIDS tattoo in a March 1986 New York Times editorial, they decided to make posters that spoke out against the blatant discrimination that was killing members of their community. For the signage, they decided to subvert the dehumanizing pink badges used by Nazis in concentration camps to identify LGBTQ+ prisoners. In late February, the group posted the SILENCE=DEATH posters throughout lower Manhattan in neighborhoods like Greenwich Village, which was not only historically a queer enclave, but also home to major book publishers, artists, and other prominent voices. “ We were trying to market a movement before the movement actually started,” Finkelstein said.

Right: Avram Finkelstein’s notebooks from 1986 documenting sketches of the Silence = Death collective’s historic poster and meeting notes (images courtesy Avram Finkelstein)

That movement to fight back against the AIDS epidemic began taking shape just weeks later on March 10, when Finkelstein and the group gathered with a crowd of a few dozen others at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center. Activist Larry Kramer gave an urgent speech calling for action. ACT UP was established two days later, and at the end of the month, over 200 protesters took to Wall Street to demand more access to experimental AIDS treatment and government action.

The SILENCE=DEATH iconography appeared at ACT UP’s second demonstration on Tax Day outside the New York City General Post Office, and the tagline stuck. Later that year, ACT UP incorporated the imagery in its neon installation “Let the Record Show …” (1987) in the window of the New Museum (the work would later become part of the museum’s permanent collection). Though this was not the only design element that ACT UP utilized to push government officials and agencies, pharmaceutical companies, and the public to enact change, it was certainly its most widely disseminated — via posters, public advertisements, buttons, and T-shirts, and more.

Gran Fury, the 11-member artist group born out of the SILENCE=DEATH collective and ACT UP, contributed numerous striking protest artworks that decried unaffordable healthcare costs, federal policies, homophobic public attitudes, and anti-safe-sex rhetoric. The group’s confrontational graphics, like ACT UP’s media-savvy public disruptions, often imitated corporate marketing ploys and government propaganda that aimed to reshape public attitudes around the AIDS epidemic and, by extension, enact tangible change; grounded in the purpose of mass distribution, Gran Fury’s artworks are currently in the public domain.

Visual AIDS Executive Director Kyle Croft noted that this copyright-free spirit, an uncommon stance for artists, was a crucial component for AIDS activism. In 1992, the arts organization similarly created broadsheet designs that were contingent on being easily reproducible.

“ It’s a way to leverage something made by a few people,” Croft told Hyperallergic.

These tactics continue to be employed by activist movements today, from Occupy Wall Street to Black Lives Matter. The present Free Palestine protests against the US-backed Israeli assault on Gaza have often repurposed many visuals affiliated with Gran Fury and ACT UP, like Writers Against the War on Gaza’s “New York (War) Crimes” custom-printed broadsheets and Jewish Voice for Peace’s transformation of the ACT UP pink triangle into a watermelon slice.

“ It’s about emotional engagement and the stimulation of individuals,” Finkelstein told Hyperallergic. “Movements are made of people, and people have to be stimulated.”