The Private Calligraphy of Henri Michaux

LONDON — Henri Michaux, a 20th-century Belgian poet and painter who spent much of his life sequestered in a relatively decrepit hotel particulier on the Left Bank of Paris, loathed being photographed.

In fact, his relatively bland and nondescript appearance made it perfectly evident that he was determined, above all else, to live under the guise of a dull species of normality — a shabby grey suit, perhaps a tad too large for the skeletal form that it bulks out, was just the ticket.

You could call him a surrealist of sorts, though he was never a clubbable man. What Surrealism gave him, as becomes evident in the course of an interview that he gave, with enormous reluctance, to the poet and art critic John Ashbery in 1961, was “la grande permission,” which telling phrase positively despises being translated.

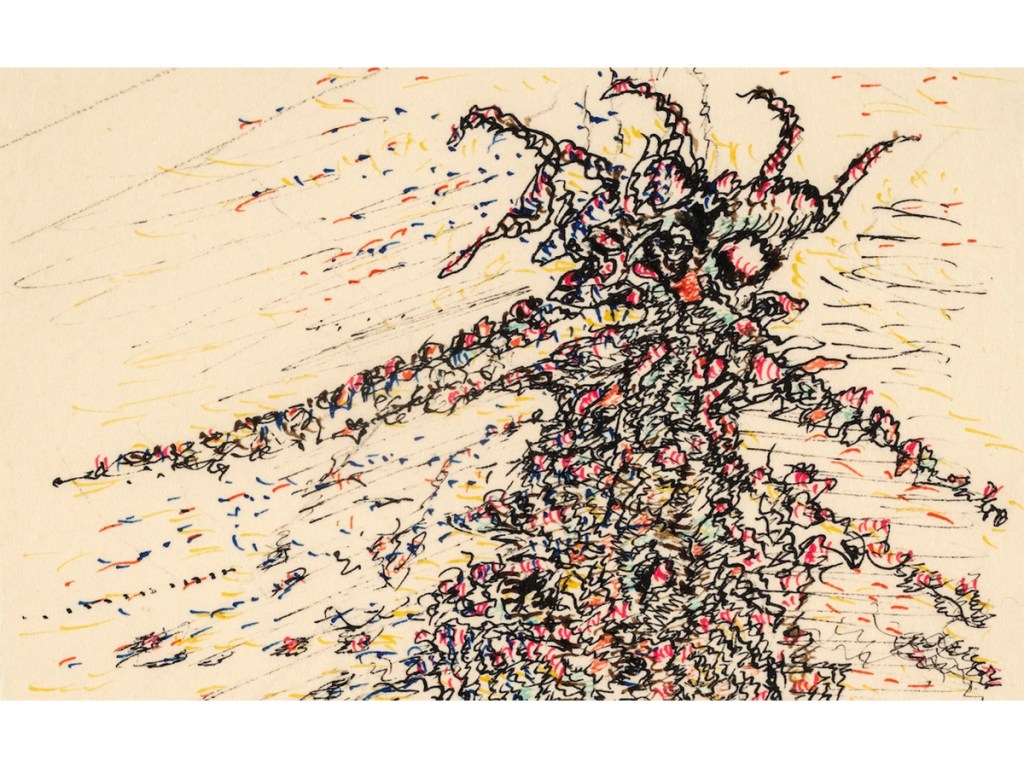

In the early 1960s, one aspect of that permission had much to do with the taking of the psychedelic mescaline, in very controlled circumstances, in order to discover what it might reveal about the nature of his own consciousness. Some time after having imbibed the stuff, and having also taken pains to drink a good deal of water, he made an entire series of drawings, relatively small ones for the most part. They are acts of mark-making of a particularly furious and intense kind.

Twenty-one of these drawings have just gone on display in the Drawings Gallery of the Courtauld Institute in London, a low-ceilinged room (it seems to squeeze down on us), with walls painted a sober grey. This environment would have pleased Michaux because it feels sequestered, private, hushed, set apart. Such whisperings as there are go on in corners. There is one small, monochromatic photograph of Michaux the man, sitting at a table, in that roomy suit of his, in a studied attitude of anti-flamboyance.

The drawings are all about detachment. Many of them are monochromatic. In the ones that use colour, that colour is quite restrained, if not mildly apologetic. They are definitely not paintings because Michaux loathed the self-vaunting theatricality of painting. Painters come accompanied by far too much cuisine, he thought. As with many poets, he felt much commonality with music.

What sort of an experience is this? Michaux no longer feels his customary fraternity with animals. He has been reduced to a furiously scuttling hand. He was, in time, to publish several books of gnomic poetry about these strange mescalinien strivings.

The first drawing was made in 1944, the last in 1969. There is often more than the suggestion of a human presence in these drawings, tiny heads and eyes; yes, often multiple eyes. The first is drawn on brown paper, as if to deter us by its lack of a commanding presence. The marks are spare and sparse. At other times, they are furiously interwoven. They morph into a private calligraphy. They vibrate until they blur. At other times, they wash gently to and fro. The captions give us the words to describe what he is doing, the impact upon himself of all this mark-making, through what bewildering worlds of the imagination he is traveling. They are the equal, in their wayward descriptive exhilaration, of all these marks on paper.

In these drawings he is in pursuit of a definition — a defining to himself, perhaps — of what exactly it is to have been under the influence, turning to his own roving hand for an answer.

Henri Michaux: The Mescaline Drawings continues at the Courtauld Gallery (Somerset House, Strand, London, United Kingdom) through June 4. The exhibition was curated by Ketty Gottardo, senior curator of Drawings at the Courtauld.