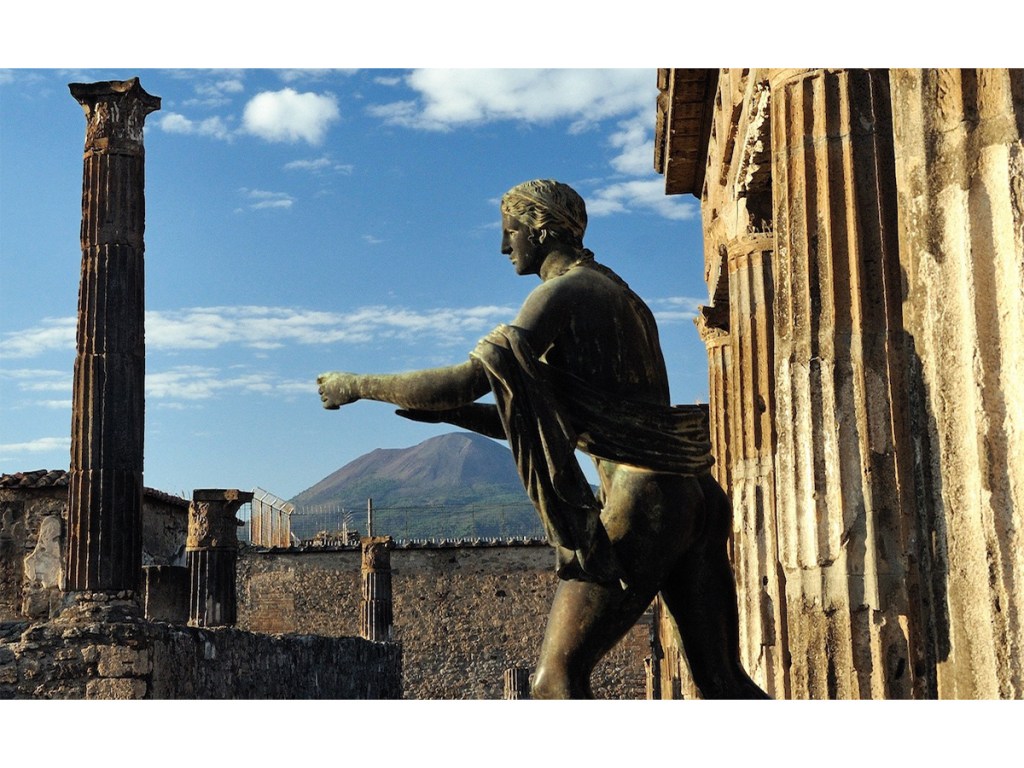

Why Are We Still Obsessed With Pompeii?

In February of 2021, German-born archaeologist Gabriel Zuchtriegel was named as the Pompeii Archaeological Park’s new director. His tenure has seen notable shifts, particularly in terms of the public image of the park. There is now more of a focus on rapid academic publication of new findings released in tandem with social media announcements and press release blasts posted online in order to amplify exciting discoveries, for one, in addition to the traditional use of multi-part documentaries airing on the BBC and PBS to expand public engagement. Last year, Zuchtriegel acknowledged that he sees the future of the site as lying outside its famed walls. Since 2023, he has pursued expansion into excavation and tourist tickets that encourage more engagement with the nearby sites of Boscoreale, Longola, Torre Annunziata, Civita Giuliana, and Castellammare di Stabia. But there is one more medium that Zuchtriegel has relied on to proliferate his narrative for the archaeological park: the book.

Earlier this month, the University of Chicago Press published the English version of Zuchtriegel’s The Buried City: Unearthing the Real Pompeii. Translated from the original German by Jamie Bulloch, the book contains 53 color photos of the artifacts, daily life, and fascinating new excavations being undertaken in the city. Zuchtriegel incorporates anecdotes from his own life and the reimagined lives of some of the 1,300 victims found at Pompeii since excavations began in 1748 to “speak vividly to [the reader’s] soul” about the site’s enduring allure. But he also wants to explain what motivates professional archaeologists like himself to dedicate their time, their bodies, and their entire lives to the field. He asks: Why are we — and often why is he — interested in antiquity in the first place?

One of the most interesting components of Zuchtriegel’s writing is that it grants us a peek behind the curtain of the internal politics of running one of the most famous archaeological sites in the world. We get glimpses of the decisions made by the Pompeii communications staff and hear of heated emotions from Zuchtriegel when, for instance, one of Italy’s daily newspapers, Il Fatto Quotidiano, cast the important 2021 discovery of enslaved quarters at Pompeii and the subsequent creation of plaster casts of the room as merely a marketing ploy by the archaeological park.

Refreshingly, Zuchtriegel focuses on the everyday lives of both the archaeologists and staff working at the site today and those who died there in the eruption of 79 CE through accessible language. He brings readers into topics of contemporary academic debates, such as the size of the city’s population, and translates inscriptions and unearthed tablets. Zuchtriegel also jumps from material culture to religion, bringing in a famed graffito noting “Sodom(a) Gomora” and takes the chance to note the ambiguity of the etching in terms of whether it refers to the Sodom and Gomorrah story in the Hebrew Bible. He notes that we have evidence for Jewish people in the city but no clear proof for Christians at Pompeii.

Though first-person narratives interlaced throughout the book are attempts at weaving ancient and modern connective threads over time and space, not every analogy is successful. The cramped quarters of the room where enslaved people lived in Civita Giuliana are clumsily compared with the confined lodgings of refugees from East Prussia after World War II. He notes these refugees were billeted in his “mother’s parents’ home in Regensburg,” but this is quite different from enslaved persons living in a confined space in ancient Pompeii. Additionally, the many American academic digs and excavators on the site, such as those connected to the University of Cincinnati, Cornell University, and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, are largely elided and erased from the narrative altogether, with focus placed predominantly on Italian excavation. While this is understandable as a way to champion Italian cultural heritage, it’s an odd choice for a book written for and sold to American audiences.

For everyday readers buying it off the shelf, Zuchtriegel’s book is a unique, unprecedented chance to gain insight into a lucrative archaeological tourism business that brings in about €20 million (~$22.5 million) per year. But it also opens up pivotal windows into the site through illustrations and the afterword about the “new dig” at Pompeii — one covering around 9,000 square meters — that go beyond the social media and documentaries. Perhaps most importantly, The Buried City brings a more humane and soulful version of Pompeii to life for the next generation of readers. This Pompeii focuses on the lives of everyday Romans and restores the ancient animus (“spirit”) to the walls, the forum, and the theater of the site. The book is part of a broader effort to increase public communications in general: a commitment to weaving a more transparent and relatable narrative into the story of an ancient city. In the end, it is also a way for a new director to add some of his own memoir to that historic tapestry.

The Buried City: Unearthing the Real Pompeii (2025) by Gabriel Zuchtriegel is published by the University of Chicago Press and is available online and through independent booksellers.